Hunter bikie turf war: How police cracked down on Finkes and Nomad bloodshed

For almost two years the warring Fink and Nomad gangs were in a bitter blood shedding turf war in Newcastle. This is the story of the war’s beginning and how cops shut it down.

Newcastle

Don't miss out on the headlines from Newcastle. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The piercing crack breaking the night’s silence is momentarily followed by the piercing pain as a bullet passes through the man’s calf as he sleeps on a couch.

It is 1am on the third day of autumn in 2018 and the peppering of bullets into the home in suburban Thornton is the latest salvo in an escalating tit-for-tat turf war between the Nomads and the Finks.

For nearly 18 months, the warring gangs have been at each other across every corner of the Hunter. Shootings, brawls, firebombings – members have been digging deep into the whole trick bag of intimidatory bikie behaviour that emanates their tough-guy image. Everything.

But this is no traditional bikie standoff where only those in leathers are in danger.

Where senior bikies make sure there is not too much heat from law enforcement. Where they carefully pick their mark – and their time – to make their point.

This has well and truly crossed the line from a private stink to a public safety issue.

And that is because the bloke asleep on the couch just happens to be a mate of local Finks treasurer Shane Hewitt.

And the casings found outside the home match the .223 military-grade ammunition fired into the home of Finks national president Andrew Manners in nearby Chisholm just two days beforehand.

Manners wasn’t home – he was in jail – but his family was when at least 20 rounds crashed through the home.

Innocent lives are in danger. And the cops are cranky.

“I remember thinking that if the bloke on the lounge was lying the other way, [the bullet] would have gone through his head,’’ Detective Chief Inspector John Walke, who was in charge of investigating the bikie spat, told Saturday Extra this week.

“The level of violence that was going on, it was just a matter of time before someone was dead.

“[And I remember thinking] it would be bad enough if it was one of the [bikie] membership, but what if it was a member of the public?’’

The cops, including the anti-bikie Strike Force Raptor, had been doing everything in their power to stem the violence. Almost everything.

It was now time to change tack, to hit the bikies from another angle.

Maybe instead of targeting them as a group of violent crooks who hid behind a code of silence, they needed to cut them out of the herd individually.

Could they take away their collective power and intimidatory tactics by extracting one bully at a time. The old divide-and-conquer plan.

The cops would use a two-pronged attack. The first was to use some legislation for the first time. Controversial legislation once used to control terrorists and expanded to involve organised crime figures.

The second was following through with an old charge that was usually just a back-up to more serious offences.

It was risky and could backfire. But senior police knew they needed to act fast.

And it was time to think outside the square.

This is the inside story of how anti-bikie cops stopped the bloodshed.

HOW THE WAR BROKE OUT

Even in the gruff and rumble world of bikies, timing can be everything.

The Nomads had long been the ruling bikie gang of the state’s second largest city.

Their clubhouse had remained successfully operating for decades despite being situated in the densely populated Chin Chen St in Islington.

Police intelligence reports would suggest that neighbours who happily turned a blind eye – and deaf ear – on any shenanigans could enjoy some expensive overseas jaunts in return for their sleepless nights.

The Newcastle chapter had already escaped several fights for survival – a massive police sting claimed some senior members when they were convicted in 2005 over a drug supply ring involving hundreds of millions of dollars worth of amphetamines.

A year later and three other members were “kneecapped” at the clubhouse.

Several Sydney-based Nomads, including well-known standover man Sam Ibrahim, were later acquitted of the shootings.

But by late 2016, things were again looking grim for the Newcastle Nomads. And this time it was coming from within.

An internal feud was simmering after a successful coup divided the chapter into two new sections – the Newcastle chapter and the Newcastle City chapter.

Adding to the tension was growing pressure from a group of young bucks who were sidling around town calling themselves “14 Street Crew” - a wannabe feeder club who thought they had everyone hoodwinked because no one would think 14 stood for the 14th letter of the alphabet, “N” for Nomads.

Enter the Finks, the Australian-born bikie gang spreading its tentacles and keen to stamp its own authority on Newcastle.

But they needed members, and not just blokes new to the bikie scene. They needed old heads and young muscle.

So, a recruitment drive began. But this was not about good interviews and better references.

Patching over is not a feat taken lightly. Once a complete no-no in bikie circles – where just leaving the group would cost the member considerable pain and money – the present-day bikie can successfully move on if they play their cards right.

But it still costs. Some estimates suggest the going rate is about $10,000 and your bike. If, in fact, you own a bike.

And many times, the new club may foot the bill. So, it can be quite lucrative if done the right way.

But the Finks couldn’t be bothered doing it any way but theirs.

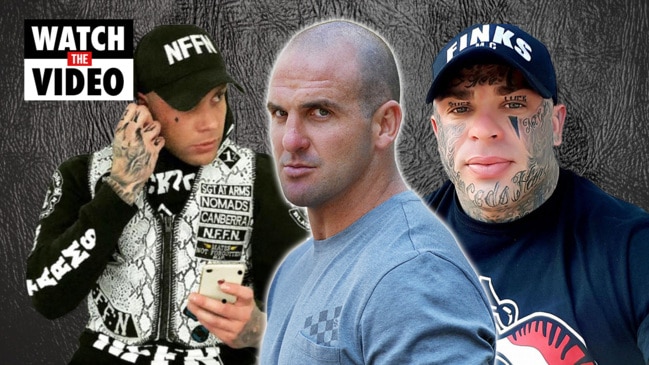

One of the first was then Comanchero gang member Adam Luke Gould. Known as somewhat of a “bikie for hire”, Gould’s loyalty was as permanent as his facial tattoos.

Even hardened crooks and cops still wince at the thought of Gould getting rid of the ink above an eye which read CFFC – Comanchero Forever Forever Comanchero.

He didn’t use a tattoo removalist, instead cutting out a rectangular piece of skin around the tattoo with a blade.

Joining Gould at the Finks were a few disenchanted Nomads. One was a hardman who had failed in his bid to be elected as one of the new chapters’ sergeants-at-arms – the officer-bearer in charge of enforcing club rules and determining what should be done to rivals. Everything includes violence.

The loss of members was becoming a problem for the Nomads and a source of tension within the 14 Street Crew, who were keen to show they meant business.

It was just a matter of time before things got physical.

It is late in 2016 and a Finks nominee had already suffered a dislocated hip when his bike was struck by a car at New Lambton. The wannabe member was wearing his colours and the Finks immediately suspect the Nomads.

Within five days, an altercation between eight Finks and a Nomad in the carpark of a Wallsend pub gets serious when a gun is produced.

And then, a week later it is all out war when members of both gangs happen across each other at a Wallsend service station.

Every weapon they could get their hands on were used – from the baseball bats in the boots of cars to the plastic windscreen wipers kept in water buckets near the bowsers.

By March, patched-over Finks are being bashed at gyms before the Nomads’ clubhouse is shot up with 10 people inside, including then Newcastle-based national president Dylan Brittliffe and the city chapter’s sergeant-at-arms Kane Tamplin.

Game on. And the tit-for-tat is also on.

The following days it’s the Nomads’ turn, with two cars belonging to the father of a Finks member firebombed at Mayfield and shots fired into the Metford home and cars of the sergeant-at-arms of the Finks’ Newcastle City chapter, Zackary Ross.

The day after the Metford shooting, the Nomads clubhouse at Muswellbrook is targeted in an arson attack and more than 30 shots are fired into the home of Nomads’ Newcastle chapter sergeant-at-arms James Quinnell at Wallsend.

The rounds pass through Quinnell’s unit and into two neighbouring units.

Over the next 12 months, there are at least seven drive-by shootings and four firebombings.

Life members are isolated in pubs and clubs before being bashed and stripped of their colours. It gets really nasty.

One of the worst incidents occurred on September 19, 2017 when the Finks sergeant-at-arms of the Hunter Valley chapter, Timothy Blake, survives an attack by two gunman who spray shotgun rounds into his car while he sits in it on the driveway of his Mayfield West home.

ENDING THE WAR

This was not to be the first time police had gone a bit left field to upset the bikies and their culture.

In 2014, one cop helped dismantle a lot of the one-percenter culture when he came across some 1943 legislation first brought in to fight against spies.

Then justice minister Robert “Reg” Downing, the man whose name adorns Sydney’s Downing Centre court precinct, brought in the Restricted Premises Act to stop spies from learning the nation’s secrets from drunken men of authority who had become compromised in illegal grog shops and brothels.

The cops decided it could also be used to shut down bikie clubhouses, using the legislation that they had snubbed their noses at authority by continually selling alcohol with licenses and using places not meant for wannabe nightclubs.

And it was brutal. With the help of the anti-bikie Strike Force Raptor, police would smash their way into the clubhouses and take everything – from bikie paraphernalia and pool tables to alcohol and bar mats. And the bars would be destroyed.

More than 50 clubhouses were raided and smashed in three years and those fighting the war between the Finks and the Nomads had shut down two Nomads clubhouses at Islington and Muswellbrook using the same legislation.

But they needed something else. And the controversial legislation surrounding crime prevention orders could be the antidote to the burgeoning disease that had enveloped the Hunter.

The legislation was first introduced to keep a close eye on suspected terrorists despite them not being charged with crime.

It was tweaked to include suspected organised crime figures. And so the police applied to the NSW Supreme Court to have crime prevention orders placed on five Nomads.

Police had to provide a mountain of evidence at the hearings and the Nomads, including

Brittliffe, Tamplin and fellow senior member Brad Bowtell, were fighting the orders.

As you would. If the police succeeded, the men would not be allowed to associate with any member of any gang, enter a pub or club across the state or travel in vehicles at night.

They would not be allowed to use encrypted communication such as Snapchat and WhatsApp and would have to surrender their phones and passwords to police whenever requested.

As the judge was making his decision, police were readying for another tactic.

And on April 3, 2018, one of the state’s largest co-ordinated simultaneous raids were made.

More than 300 officers were involved in the raiding of 31 properties across the Hunter that were linked to the Nomads and Finks.

And they did not miss.

They seized everything they lawfully could – bikes, colours and any bikie paraphernalia they could find. Every single shirt and jumper with a Finks or Nomads insignia.

It is said at least one Nomad was only left with his underpants because all he had in his closet and drawers was clothing emblazoned with Nomads motifs.

“You have taken away their identity [as bikies] and for many of them, that is a lot more significant than anything else,’’ Detective Superintendent Jason Weinstein, the head of anti-bikie squad Strike Force Raptor, told Saturday Extra.

Although only 11 people were charged at the time, the ripple effect was in motion.

By the end of April, the Supreme Court had ruled in favour of police and brought down most of the heavy impositions that the cops wanted, although they could still go to the pub.

Finks members were next and five, including Manners, suspected state president Benjamin Main, Newcastle chapter president Troy Vanderlight and Cessnock chapter president Mitchell Cole, were placed under the serious crime prevention orders. And then, the police introduced their coup de grace — charging dozens of bikies and associates with either directing a

criminal group of being involved in a criminal group.

The count had almost always just been a back-up charge for more serious criminality. But this time it was used as a shot across the bow to anyone who had anything to do with the bikie gangs — from the national presidents to the locksmiths who helped them change clubhouse locks.

It would destroy the code of silence that the bikies had worn as a badge of honour.

In all, 55 people were charged with the criminal group counts. And all were convicted, the last just over a month ago.

The war was over.