Parramatta historic buildings Royal Oak, swimming pool lost to development

It’s at the centre of one of the nation’s biggest development booms but progress has come at a cost for history-steeped Parramatta.

Parramatta

Don't miss out on the headlines from Parramatta . Followed categories will be added to My News.

Parramatta’s heritage has suffered several blows as development and transport projects claim casualties such as the Royal Oak Hotel, the beloved War Memorial Pool and the imminent destruction of Victorian villa Willow Grove.

As Sydney’s second settlement, the suburb, also known as Sydney’s second CBD, was brimming with Victorian gems, character-filled pubs and grand homes that are now declining at the hands of government infrastructure and ambitious developers.

The controversial decisions mean heritage advocates have their work cut out for them.

North Parramatta Residents’ Action Group spokeswoman Suzette Meade has been instrumental in fighting to retain the 1870s-built former maternity hospital Willow Grove, which the government wants to “relocate” to make way for the Parramatta Powerhouse Museum.

She said Parramatta’s rich heritage was under appreciated.

“Parramatta’s exceptional collection of heritage as the second colony would be revered in any other country with pride,’’ she said.

“Western Sydney battles many prejudices and respect for our significant heritage from the state government is front and centre.’’

National Trust NSW’s Parramatta president Cheryl Bates echoed the remarks.

“The National Trust continues to have grave concerns about local and state decisions that impact on Parramatta’s rich heritage,’’ she said.

“Many buildings identified as significant — both to the local community and significant to the state — are being sidelined to make way for development.’’

Parramatta state Liberal MP Geoff Lee defended his government’s treatment of heritage.

“We have committed more than $100 million over 10 years for restoration works and infrastructure for the North Parramatta Heritage precinct. This investment will make the North Parramatta Heritage site Australia’s best heritage precinct.’’

He said the government also supported the Parramatta Female Factory Precinct’s World Heritage listing and invested more than $50 million on the refurbishment of the Old Kings School, transforming it into the new Bayanami Public School (formerly O’Connell Public School).

The project was so successful it won the National Trust’s 2018 Heritage Award for Adaptive Re-use, he added.

WHAT’S GONE

THE ROYAL OAK

The government boasts about the $2.4 billion Parramatta Light Rail providing a 12km link to Sydney’s expanding centres, from Westmead to Carlingford, but it also spelt the end of one of the nation’s oldest pubs, the Royal Oak.

The 207-year-old pub was bulldozed in the dead on night on May 19, 2020, signalling the start of construction on the contentious rail line.

With it went fireplaces, pressed metal ceilings and a favourite watering hole to thousands of patrons, from business workers to Parramatta Eels players and supporters.

Sirius ship First Fleeter William Tunks’s son John built the Royal Oak, originally named the Shamrock, Rose and Thistle, on the corner of Church and Ross streets, in 1823.

Convict John Metcalf established it as an inn in 1813 before Tunks built and ran what was one of Australia’s oldest pubs.

Lorraine George, who was a descendant of the Tunks’ family was part of a passionate community campaign calling on the government to save the pub by unsuccessfully lobbying it to reroute the light rail to O’Connell St.

The pub’s former Cobb & Co stabling yards, which were used when horse racing was held at Parramatta Park, remain at the back of the building.

RANLEIGH HOUSE

This glorious, pink and white three-storey abode was built in 1863 for Parramatta mayor Samuel Burge and was later the romantic setting for a reception venue.

The home boasted features not out of place in a palace: a ballroom, gilted mirrors, a spacious master bedroom, towering rooms, a steep, sloping roof, pre-Victorian china cabinet, french windows with burgundy drapes and a 21sq m kitchen.

Perched at 12 The Park, it stood on the boundary of Parramatta Park and overlooked the Golf Club and in the 1960s, local newspapers referred to it as the “district’s leading and most sought after social reception house it was very popular for decades.

It was perfect for birthday parties and considered a bride’s first choice for wedding receptions, with its excellent catering and views of Parramatta Park,’’ Parramatta Council website says.

Mr Burge lived at Ranleigh with his family until 1873, when Reverend Thomas Spencer Forsaith bought the house and lived there for two years.

After a succession of owners including George Oakes, who was a member of the original Parramatta Park Trust, the Fullager family owned the property from 1895 to 1959 and added the third storey and a ballroom in 1896.

It was leased to the King’s School Parramatta, to house their juniors, between 1908 and 1910.

Jack and Chris Rapp bought the house in 1959 and used it as a wedding reception business for 17 years.

But proving Parramatta’s history battles are nothing new, the house’s death began in 1976 when it was sold to a couple who continued the business under the name Ranleigh House but it was slated for development.

An interim conservation order enforced in 1978 was not renewed and in 1988 it was demolished to make room for a Housing Department project.

This was despite the National Trust, Holroyd Council and the Parramatta Park Trust lobbying to save it.

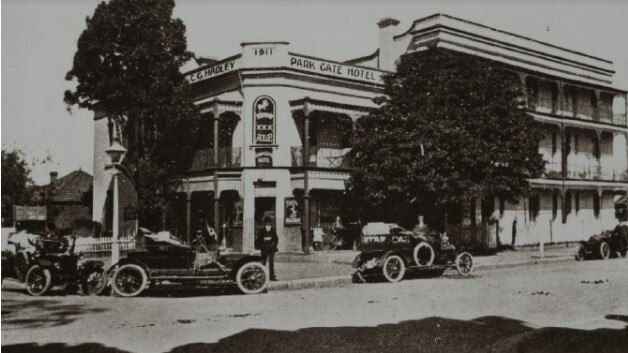

THE PARK GATE HOTEL

The Royal Oak was not the first watering hole consigned to the history books. In 1959, the Park Gate Hotel, on the corner of George and O’Connell streets, was gone after 80 years keeping Parramatta hydrated.

The stately Victorian pub was adorned with iron lace and designed by J F Cripps, who gave the building its name after Parramatta Park.

Patrons had a view of the park’s picturesque George Street Tudor Gatehouse (which remains standing) from the pub, which John Cripps’ wife Annie purchased for 7000 pounds in 1879. Mr Cripps was a confectioner who once managed The Coffee Palace Hotel in central Sydney before it was burnt down.

Their son, John Fisher Cripps, Junior was the proprietor and manager of the Park Gate Hotel.

These days, you’ll find more lawyers than drinkers on the site, with the Family Law Court occupying the site.

HIAWATHA

Just like Ranleigh, Hiawatha was a magnificent residence turned function centre, but was demolished to make way for a bowling alley and then an office tower.

It was part of the thriving landscape of Victorian villas that graced Parramatta in the Victorian era. Perched at 70 George St, the town house was built for drapery merchant and Parramatta Mayor Joseph Withers in 1883 when it stretched over a double block George and Phillip streets, where the Octagon now stands.

Withers had the property built for his growing family which included his children Ernest A. F, twin daughters Blanche Naomi Maud and Gertrude Laura May.

After a string of owners, Hiawatha was transferred to the Federation of NSW Police Citizens Boys’ Club in 1953 until 1962 when they moved to larger premises.

The breathtaking Hiawatha was demolished to make way for the tenpin bowling alley, the Parramatta Indoor Bowl Centre before the Octagon was built between 1978 and 1984.

However, one of Parramatta’s most familiar commercial blocks is likely to be demolished to make way for a $338 million, two-tower development with a hotel and shops.

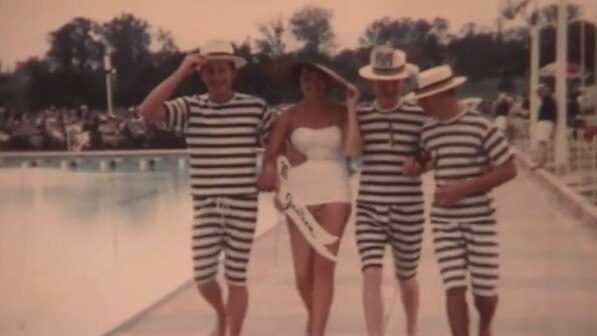

PARRAMATTA WAR MEMORIAL SWIMMING CENTRE

The water slides, diving boards, Olympic pool were as much a landmark along O’Connell St as Parramatta Stadium but were obliterated in 2017 to make way for the $300 million Bankwest Stadium.

The pool was built in honour of those who had lost their lives in World War II.

North Parramatta Residents’ Action Group collected more than 3600 signatures that opposed the 58-year-old pools closing and, in March 2017, implored then Infrastructure Minister Andrew Constance “pause the stadium project for a minimum of six months to allow for genuine and transparent consultation, allowing alternative planning of this sports precinct ensuring that the stadium and the pool to can continue to coexist”.

But while the stadium opened in 2019, locals have been left without a pool for four summers and will have swelter through at least two more, with the $77 million pools not set to reopen until 2023.

WHAT’S UNDER THREAT

WILLOW GROVE

The most prolific building under threat in recent times, Willow Grove’s history could disappear for the much-maligned $767 million Parramatta Powerhouse Museum, dubbed the “milk crate on stilts’’ and the “Frankenstein building”.

North Parramatta Residents’ Action Group (NPRAG) has spearheaded a vocal community campaign to allocate the museum elsewhere in Parramatta so the double-storey Italianate property can remain.

Despite 90 per cent of the 1300 public feedback submissions objecting to the Powerhouse location because of the heritage under threat and it being on the flood-prone site, the government announced it would move it brick by brick.

Granville state Labor MP Julia Finn labelled Arts Minister Don Harwin’s comments that it would be “restored to its former glory’’ a “bogan brain fart’’.

Supporters used International Women’s Day on Monday to “stop the heritage vandalism in Parramatta” and highlight how women shaped Willow Grove’s history.

Annie Gallagher purchased the land for Willow Grove and used her money that financed the construction of the Phillip St from the proceeds of her drapery business.

Several entrepreneurial Parramatta businesswomen owned the site, before it was used as a maternity hospital between 1919 and 1953.

“Stop the reckless demolition of Annie Gallagher’s Willow Grove,’’ Powerhouse Museum Alliance Kylie Winkworth said.

“Stop the NSW Government erasing women’s heritage places and stories in North Parramatta Female Factory precinct. We must listen to women, hear their voices, and protect their

places for the future”.

But defiant heritage advocates remain hopeful they can save Willow Grove.

Last week, the Maritime Union of Australia lent its support to the Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union green ban on the site.

“If the Berejiklian government decides to try and push on with this senseless destruction we will stand alongside the community to physically protect our shared heritage,’’ NSW branch secretary Paul Keating said.

Willow Grove’s neighbour St George’s Terrace, a row of two-storey terraces built in 1881, has been spared from the bulldozer and will be refurbished.

THE MANSE

Just a block from the $3.2 billion Parramatta redevelopment, another major project is threatening the charming federation building The Manse from standing at the corner of Hunter and Marsden streets.

ICC Development Group has proposed a $1.1 billion tower housing a private hospital, five-star Sheraton on the Square hotel with a helipad, and Michelin-star restaurant in a tower called the medi-hotel.

The development will house 17,000sq m of hospital space over nine floors at its base, medical commercial suites, including IVF and physiotherapy over eight storeys in the centre, and the luxurious hotel on the summit with 360 degree views of Sydney and surrounds.

When revealing plans last year, ICC chief executive officer Harold Dakin said the project would be the “final piece of the jigsaw puzzle to complete the Parramatta CBD transformation”.

But the Queen Anne revival style 1895 property could become another casualty of Parramatta’s development boom if the medi-hotel gets the green light at 41 Hunter St.

National Trust of Australia’s Parramatta branch president Cheryl Bates slammed the project for imposing on St John’s Cathedral before calling on developers to stop treating Parramatta’s heritage building as an inconvenience “when they should be seen as an integral part of the city given its long and rich heritage”.

Ms Meade called for the developer to work around The Manse, which was built between 1895 and 1897 for Scottish Reverend John Paterson, who was ordained into St Andrew’s Presbyterian Church at Parramatta.

The charming two-storey federation home was designed by architect Francis Ernest Stowe, of Marsden St, Parramatta, and is on the local heritage register. Its most recent use has been as a solicitor’s office.

OUR LADY OF MERCY COLLEGE, PARRAMATTA

The 130-year-old school’s $28 million makeover could change the familiar facade of its Ross St entrance.

Under its masterplan project, the four-storey brown brick block will be demolished. Even though it is not heritage listed, it adjoins the heritage-listed 82-year-old cream Brigid Shelly building and will transform the view of the school from Ross St.

However, the school said the project would be vital to meet the needs of more than 1000 students and would house learning areas, a rooftop terrace and landscaping that would open the view of the Mother Mary Clare Dunphy Memorial chapel, built in the 1930s.

The contemporary building, which is being assessed by a state government planning panel, is considered vital by the school because the former block is only useful as a storage space.

A suspended walkway linking students from the Brigid Shelly building to the opposite side of the school is also part of the project.

The college’s main site dates back to 1889 and its Roseneath Historic Precinct dates back even further to 1837.

A school spokeswoman said the school took a sensitive approach to heritage and the masterplan built around historical buildings.

“The plan builds around our heritage buildings; it does not involve the demolition of any heritage buildings, but instead sympathetically builds around them to bring out and highlight their heritage features, such as archways,’’ she said.

“We consult in the planning stages and throughout the whole building process with our heritage architects and we work in close collaboration with the local council and their committees, seeking relevant expert advice at all stages.”

ST JOHN’S ANGLICAN CHURCH HALL

St John’s Anglican Church is one of the most captive buildings in Parramatta’s CBD but $400 million plans to transform the precinct will dwarf the sandstone cathedral and banish its neighbouring, 108-year-old hall.

The hall has local heritage listing but will be replaced with two towers — including a 46-storey block for three auditoriums seating up to 1000 people and 44,000sq m of office space for 4000 jobs.

The second, southern building would be an eight-storey residential tower possibly to house an aged care centre and student accommodation.

The plans have been created for the parish’s 100-year masterplan after the church said it needed to bring more than 1000 worshippers into the 21st century.

In December 2019, when plans were revealed, St John’s minister Bruce Morrison said the hall’s heritage value did not outweigh the benefits the public would gain from the redevelopment.

Its proximity to the vast $3.2 billion Parramatta Square development prompted him to call it Parramatta Square West.

THE ROXY

The beloved Roxy Theatre was once one of Sydney’s most picturesque cinemas that boasted a stunning Spanish Mission style facade gracing George St.

While the 91-year-old Roxy is not earmarked for the bulldozer, heritage advocates — including Toongabbie boy turned Hollywood filmmaker Bruce Beresford — want to restore the imposing cinema to its former glory and use it for theatre and music.

![]The Roxy Theatre in Parramatta. Picture: Angelo Velardo](https://content.api.news/v3/images/bin/8a95a47ff4a830eaf23cce5ee17301cb?width=650)

But the plans go against owner David Kingston’s vision to covert the Spanish-style building into a “premier pub, pokies and entertainment venue’’.

The plans were revealed in June 2019, when the Land and Environment Court rejected designs for a $96 million, 33-storey tower redevelopment of the Roxy, citing it would harm its heritage value.

The 1930s-built Roxy has five heritage listings at national, state and local levels, and was originally used as cinema when it seated 1923 patrons.

Mr Kingston bought the Roxy in 2002 and it reopened as a nightclub before the curtains closed again in 2014.

“This is a once in a lifetime opportunity to create a landmark precinct of healthy, inclusive space for community to exercise, socialise and watch professional sport — make this one of your greatest legacies.”

CUMBERLAND HOSPITAL PRECINCT

The grounds of the Cumberland Hospital, which straddle Westmead and North Parramatta, won’t be quiet much longer.

The state government is building the light rail through the hospital site and most recently announced plans for a tech start-up hub and Sydney University campus at North Parramatta.

The university hopes to attract more than 25,000 students and 2500 staff by 2055 and provide “affordable student and staff accommodation”.

Jobs and Investment Minister Stuart Ayres said the Western Sydney Startup Hub would activate 1500sq m of the North Parramatta Heritage Core by “sensitively restoring’’ three buildings including the circa 1876 Hospital Spinal Range Building and circa 1892 Kitchen Block.

He said the project, to open late this year, will include a cafe and events centre, and

attract entrepreneurs and innovators to the site.

But the project’s location — alongside the Female Factory site, which is one of Australia only intact convict buildings — has drawn the ire of heritage campaigners.

North Parramatta Residents’ Action Group said it showed the government was treating western Sydney’s heritage as second best and the heritage precinct should not be used for business.

The group called for the government to treat the Female Factory as it has the Hyde Park Barracks in central Sydney, where the government funds it as a museum and operates it with Sydney Living Museums.

The Female Factory was constructed between 1881 and 1848 and designed by convict Francis Greenway, who modelled it in a similar fashion to the Hyde Park convict barracks.

The Fleet St institute was used as a workplace, prison and medical facility until 1847 when it was repurposed as an a lunatic asylum for convict women.

NPRAG has also opposed the neighbouring Sydney University site, saying “it’s an unsolicited bid on public land’’.

Spokeswoman Suzette Meade said Parramatta Council’s development control plan would allow for 25-storey buildings on the Cumberland site but a CFMEU green ban from five years ago remained.

In 2015, UrbanGrowth planned 1600 apartments in high-rise blocks for the Cumberland site but were canned after huge community outcry.

The Cumberland Hospital site is regarded as one of the nation’s richest historical places and has been used as a mental health institute since 1818.

Ms Meade called for the government to consult the community more closely.

HOUISON’S COTTAGE

While the Parramatta Light Rail has derailed history at North Parramatta with the bulldozing of the Royal Oak, the government’s Metro West project could threaten another old treasure at 64 Macquarie St.

The elegant, 179-year-old Houison’s Cottage, formally known as Kia Ora, flanks the site earmarked for the train station, which will be built on the Horwood Place block bounded by George, Macquarie, Church and Smith streets.

Parramatta architect and builder James Houison constructed the cottage in 1842 in the Colonial era and alterations in 1955 saw the building adopt a Georgian facade.

Sydney Metro said the building would be retained, protected and integrated into the Metro station precinct.

“Through the ongoing design and development process, Sydney Metro is committed to protecting heritage items during construction,’’ a spokeswoman said.

However, it failed to address questions about what it planned to do with Houison’s Cottage once it was compulsorily acquired.

The building is owned by LCI Partners’ Frank Cavasinni, who wants to retain the cottage, which he purchased 20 years before restoring it after squatters occupied the space.

It is now used as a bric-a-brac store but was previously used by a law firm.

THE ALBION

Just like the Royal Oak, Parramatta is set to lose one of its favourite watering holes, the Albion, when developers tear down the 138-year-old landmark and replace it with 405 units.

Wine bars, 36 apartments for seniors, a function room, cinema, billiard rooms, indoor bowls will sprout up in the 51-storey block at Harris and George streets, opposite the light rail.

But it will take away part of Parramatta’s heart and soul, councillor Donna Davis says.

“One thing that really frustrates me about the site is that we are losing another pub,’’ she said at a council meeting.

“When you walk past the Albion on a Sunday night, on a Saturday night, the music is happening, it’s a happening place to be, it’s a popular place, it’s a destination.

“Now the people that are building this new, fandangled apartment block on this site are saying that they are going to build another pub but we know it’s not going to be the same.’’

She said other restaurants built under apartments in Parramatta had experienced restrictions.

“We are wanting to build a night time economy, we are wanting to have a city that is alive but the Albion is one place in this city that is already alive,’’ Cr Davis said.

“I know it’s very far down the track but it needs to be mentioned, it needs to go on the record that this city cannot lose another stand-alone pub like this one.

“We are going to lose the Albion, we’ve lost the Royal Oak, we’ve lost a significant number of pubs in Parramatta over the years. You go to other towns and cities around Australia of a similar age to Parramatta, and even younger, and they still have their pubs on every corner.

“They are places that people really treasure. They mean a lot to those cities and they mean a lot to the fabric of that city and losing the Albion is going to be a great loss to the fabric of this city.

“Generations have had wonderful memories from that place and I know this development is way down the path but it needs to be said and it needs to be prevented from happening on other sites. Whether or not they be pubs, whether or not they be other significant buildings that offer something to the fabric of this city.’’

The “Albie’’ opened at its existing site in 1882 and was demolished in 1924 to make way for the new hotel.

The Solomon family acquired the hotel, just around the corner from the Gasworks Bridge, in 1986 and opened a beer garden for daytime patrons while the nightclub draws a younger crowd when the sun goes down.

MORE NEWS

Sicilian Restaurant Parramatta closes on Church St

Parramatta Eat St light rail fight ramps up

WE’RE STILL HERE FOR YOU

We’re still here for you. For trusted news that matters, and to support local journalism, go straight to the source:

● Visit parramattaadvertiser.com.au

● Get local news direct to your inbox. Search and sign up for the Parramatta Advertiser here: https://www.newsletters.news.com.au/dailytelegraph