Northmead Ambulance, ice scourge: Drugs unleash harm on paramedics and community

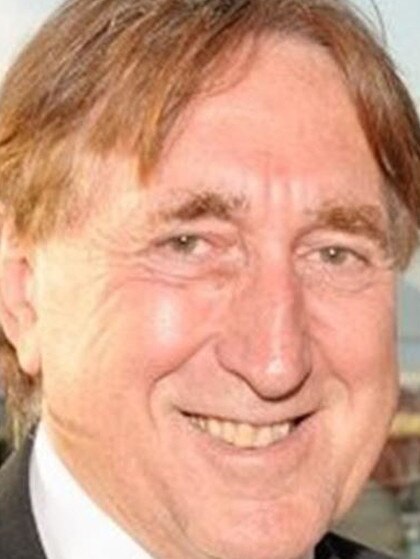

Paramedic Kevin McSweeney has dealt with a lot of tragedies in his time but says the way the drug ice unleashes its harmful impacts on the community is on another level.

Parramatta

Don't miss out on the headlines from Parramatta . Followed categories will be added to My News.

- Chaplain recalls horror of family shootings

- Firefighters face inferno challenge

- ‘You’re nicked’: dramatic twist in taxi police chase

Seasoned paramedic Kevin McSweeney can’t escape the drug ice.

The way it ravages its users and the community, how it triggers a constant stream of horrific and violent incidents and how ambos are left to deal with its devastating impacts.

“We respond to patients on ice almost daily and that’s honestly speaking,’’ McSweeney, who is based at Northmead ambulance station, said.

Along with suicides, cardiac arrests and shootings, the illicit substance is a source of much work for McSweeney and fellow paramedics.

“Ice is an insidious drug; it really takes away the person it was and changes them into something quite terrible,’’ he said.

“Personally I haven’t (been attacked) but the increase in violence to paramedics is alarming at the moment and a lot of it does come down to drugs such as ice and mental health issues.

“To be honest, it doesn’t compare. It’s at another level, completely at another level.”

Last year, in what was not an isolated incident, it took a team of emergency service workers — and drugs — to sedate a man from Granville in his 30s high on ice.

“We went to someone who was affected by ice in his house and he was extremely violent and at that moment in time I think we had six police officers and four paramedics and it took that many to restrain that fella,’’ McSweeney said.

“At the end police held him down and we had medication that would basically put them to sleep.

“What we need to do is be mindful of our own safety so we need to be sure there is somewhere to retreat so there is an exit plan and if we know we’re going to someone with ice or drugs involved, it’s prudent to wait for police to be on scene to give us assistance.

“They’re always there on the scene because we concentrate on what we’re doing.

“Police are fantastic to paramedics. They always cover us, have our back, make sure we’re safe. I think the relationship between paramedics and police is pretty special.”

NSW Health data shows the proporition of people who used ice in NSW in 2016 remained low at 0.7 per cent but an increased number of people who used the methamphetamine

reported more frequent use, an increase in injected use and use of a high purity crystal form (known as ice).

The 2018 report, Methamphetamine Use and Related Harms in NSW, showed the number of people harmed by ice soared from 2010 and peaked in 2016-17, with people aged 24 to 44 experiencing the higher rates of harm.

These harms were seen through methamphetamine-related emergency department

presentations and hospital admissions.

The rate of methamphetamine-related emergency department presentations in the state jumped from 0.8 per 1000 presentations in 2011-12, to a peak of 3.0 per 1000 presentations in 2015-16. The rates of methamphetamine-related emergency department presentations stabilised at 2.4 per 1000 presentations in 2017-18.

FAMILY HORROR

When gun shots from a double shooting shattered a usually peaceful northwest Sydney neighbourhood on a winter’s night, paramedic Kevin McSweeney was one of the first responders.

It was a chilling night when a gunman pulled the trigger on his own children.

McSweeney, a NSW Ambulance first responder is calm and collected and has dashed to many shootings — some gang-related drive-bys, others involving bikies — but on the night of July 5, 2018, this was a domestic violence incident that turned fatal.

Unfathomably, John Edwards had opened fire on his two teenage children.

Estranged from his wife and their mother Olga, Edwards shot Jack, 15, and his sister Jennifer, 13, in a bedroom at the West Pennant Hills home they shared with their mum.

A paramedic of 20 years, McSweeney raced to the Hull Rd home.

It was about 5.30pm. Many Sydneysiders were spilling from trains and buses on their way home for dinner.

McSweeney knew two people had been shot. Are they both dead? Is one alive and another dead?

Just some of the questions racing through his mind.

“There was a lot of police and they explained that two children had been shot and, on examination, unfortunately they were deceased,’’ he said.

He found their lifeless bodies in an eerily quiet scene.

“They’d been shot multiple times,’’ McSweeney, a father of three adult children, said.

“It was tragic and horrendous. I guess it sticks a bit more with you because the tragedy was it was their dad who shot them.

“I guess you think of the fear they would have had and the fact it was their dad.”

Edwards, a 68-year-old retired financial planner, had stalked the children in a hired car so he could follow them without being recognised.

He was later found dead inside his Normanhurst home with a self-inflicted gunshot wound.

Two handguns used in the double murder were recovered from his house.

Twenty minutes after Insp McSweeney reached the crime scene, their distraught mother Olga arrived and collapsed.

Five months later, the 36 year old took her own life.

“I thought ‘what a tragedy’,’’ McSweeney said.

“She went to work one day, came home and her children had been murdered and then it spiralled to that point where she took her own life.

“I think as a parent you probably have some understanding of that but it’s just an absolute tragedy.”

Outside, noise rippled through with police cars and ambulances lining the street.

“There was just police, paramedics and then cordoned off on both ends, and then a huge media contingent,’’ McSweeney said.

“In the role I have as an inspector you often have several plates spinning, on different things happening, and I think you learn to do that.

“That part of the role is to speak to the media and the public have that right to know what’s going on and what’s newsworthy.

“I guess, you’re in that paramedic work mode and you’re doing the best you can for the patient and then once you do that you’ve got to turn to that other media role and answer people’s questions as best you can and respect people’s privacy.”

Throughout the West Pennant Hills ordeal, the former tiler has the composure that comes with two decades on the job.

“As a group of paramedics, we had a debrief that night and then I had a lot of phone calls from friends to check if I was OK,’’ he said.

“I hope the public recognise we’re normal people like everyone else, so I’m a normal husband and dad, and so are other paramedics and police, so we have the same range of emotions.

“And if you’re human, there’s times that it’s upsetting but at the given time, we have a role to do and that’s what we hopefully do really professionally.”

Lifeline: 13 11 14