Local developments loom as major factor ahead of NSW election

Massive infrastructure developments are changing the face of Sydney and our northern suburbs are bearing the brunt of the impact. What does this mean for the 2023 NSW election?

North Shore

Don't miss out on the headlines from North Shore. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The NSW electorate of North Shore, a bridge from Sydney’s CBD, has been subject to massive transport infrastructure development to benefit the whole city. Other north shore electorates also carry the impacts. But the work divides communities. Some people want it but others argue the NSW government is destroying the very features that give their suburbs their identities.

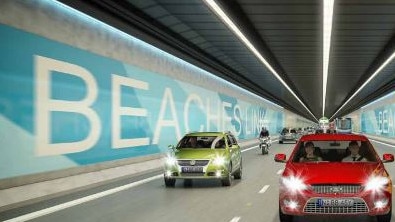

The Beaches Link tunnel

The Beaches Link tunnel was first thought of decades ago to solve the problem of traffic congestion funnelling across the Spit Bridge from the northern beaches. The 7.2km tunnel from Cammeray to Balgowlah was officially promised in 2017 by then premier Gladys Berejiklian, in a gesture some commentators saw as an election sweetener for Manly voters.

While many northern beaches residents want the tunnel, today, the Tunnel Concerned Communities group combines 14 groups opposed to it. And beyond them, a March 2021 submission from the Balgowlah Residents’ Group to the Department of Planning argued “more than 40 per cent of the benefits go to people and corporations who do not necessarily reside in the northern beaches”.

They said their communities would not recover from the destruction of defining natural bushlands and other green spaces.

In contrast, closer to the city, the 2017 tunnel announcement was embraced in Mosman municipality because it would take traffic density off Military Rd, returning it from a choked thoroughfare to a more peaceful road. Mosman councillor Tom Sherlock outlined his vision for a Champs-Elysees-style Military Rd with trees and cafe-lined pavements.

With planning approval technically still pending in June this year, Premier Dominic Perrottet announced the tunnel link would be delayed from its 2023 start due to surging construction costs and global labour shortages.

Mosman Mayor Carolyn Corrigan immediately expressed disappointment – and her council strongly objected to the delay.

Mosman businessman Peter Papas, of the Sensible Traffic Action Group, with pro-tunnel members from Manly to Cremorne said: “The Liberal government missed the opportunity because of incessant delays in several interdependent infrastructure projects. In the event that we end up with a state Labor government, we will never get the tunnel.”

It’s a reasonable prediction. In October 2021, NSW Labor leader Chris Minns said funding for the tunnel should be scrapped for new public transport in Sydney’s west.

North Shore Member Felicity Wilson defended the government’s decision to delay the tunnel: “We’re being transparent. I know people will be cynical right up until we’ve got the shovels in the ground, but it’s only right that we should manage expectations.

“Most people understand that there are major forces at play – such as current pressure on construction costs and labour.

“The government is 100 per cent committed to the project.”

But Papas is disappointed that Wilson has not pushed the issue harder with her government.

“She is representing the pressures of government over those of her own electorate,” he says.

“She has supported it but she is not the vocal advocate we need.”

Cammeray Park

The government describes Warringah Freeway as “one of the nation’s busiest and most complex roads”. Its upgrades are to “increase safety for motorists by reducing the need to merge and weave (and) public transport will be more reliable”.

Upgrade work has turned Cammeray Park into a muddy quagmire and part of Cammeray Golf Course, compulsorily acquired, has lost its green canopy.

Trees are at the heart of the “leafy north shore” and Cammeray. Last September, residents graphically protested the threat to almost 1000 mature trees by planting 575 paper trees to represent those already lost.

In October, North Sydney Council called on the government not to enter into any contracts for the third stage of the planned projects before the 2023 state election, arguing the government’s commitment to the freeway disregarded the impact on the people of North Sydney.

Council is also supporting residents beside the bridge, who have tied purple ribbons around trees on the last pocket of green before the bridge. They say this loss is not for the roadway itself, but to accommodate contractors’ equipment.

Harbour Bridge ramp

The Sydney Harbour Bridge cycleway runs between Millers Point and Milsons Point on its western side. The government says it’s critical to Sydney’s bicycle network.

Plans for a 200m-long elevated pathway along the Bradfield Park side of the bridge were confirmed in April after different options were put on public display.

“More than 80 per cent of respondents in a June consultation by Transport for NSW were supportive of ramped access to the cycleway and 68 per cent supported the linear design which has been selected,” NSW Minister for Infrastructure, Cities and Active Transport Rob Stokes says.

But some residents question whether the government should alter the original Art Deco style of the bridge, saying the bridge is an international icon.

“The heritage value of the Sydney Harbour Bridge must include the area in which it is located,” says Kirribilli resident Michael Gill, who agrees cycling should be supported.

“But the framing of the bridge physically and historically is unique. And now we will destroy it with an unnecessary piece of modern entitlement. A cycle landing strip, dominating, redefining, busy and noisy. Why?”

Luna Park

North Sydney’s heritage-listed Luna Park began in 1935 and has been owned by the Luna Park Reserve Trust, an agency of the NSW government, since 1990 to protect its use as an amusement park. But North Sydney councillor Ian Mutton says today Luna Park needs protection from the state government itself.

In 2018, the NSW government argued in the Land and Environment Court that Luna Park needed development consent for any developments. But shortly after, the government changed its position.

“So at first the state government sided with the community – it took Luna Park to court and won an order requiring Luna Park to comply with the planning laws,” Mutton says.

“The victory must have come as a shock to the government because it then amended the planning laws to exclude Luna Park from their application. What was galling to the community was that the process leading up to the amending of the laws was carried out with no community consultation.”

He says in 2017 local member Wilson sponsored “an amendment to the planning laws to relieve Luna Park of the ‘burden’ of obtaining approval for new rides” and, after this, he lost confidence in her capacity to protect Luna Park.

A little pocket of garden symbolises further the recklessness of the NSW government when it comes to communities, Mutton says.

“Lavender Green was intended to be kept as a park available to the community with no permanent structures. Even with the requirement that there be no permanent building, a pavilion occupying around a third of the Green was erected back in 2016,” he says.

“It’s permanently fixed to the ground and has fixed water and electricity connections – if that’s not permanent, what is?

“This is what we come to expect from a government that has taken a half of Cammeray Golf Course to build a road and resumed most of Bradfield Park to build a bike ramp.”