The giant harbour pool at Manly was a headline attraction for more than 40 years

For more than 40 years the giant harbour pool and promenade between Manly Wharf and what is now called Federation Point was a local landmark.

Manly

Don't miss out on the headlines from Manly. Followed categories will be added to My News.

For more than 40 years the giant harbour pool and promenade between Manly Wharf and what is now called Federation Point was a local landmark.

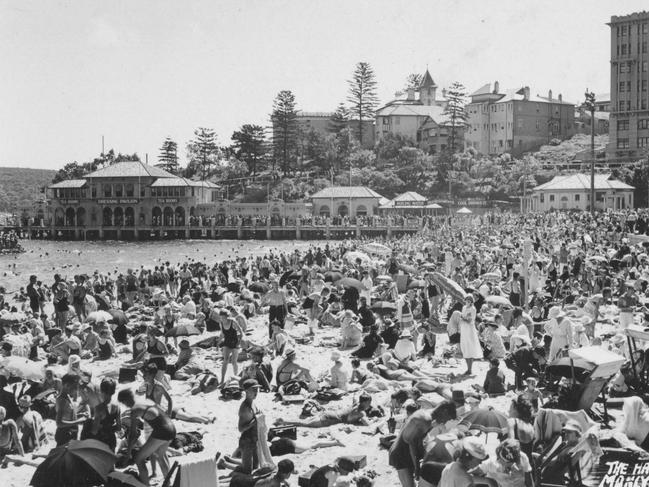

Generations of local residents and millions of visitors to Manly revelled in the pool’s vast size and in its safety from sharks.

And while it disappeared overnight in May 1974, for Sydneysiders in general it might have seemed as though the pool had been built overnight as well.

Ever since Manly’s founder, Henry Gilbert Smith, began planning what he envisioned as the Brighton of the South in the 1850s, the area has been home to scores of attractions, all designed to amuse tourists and separate them from their money.

Aquariums, fairground amusements, open-air cinemas, a miniature train, a mutoscope, a giant water slide, merry-go-rounds, baths, theatres and dance halls all vied for the attention of the tourists as they poured into Manly with each arriving ferry.

There was even a proposal to build a 275m pier jutting into the Pacific Ocean, similar to those in England, complete with promenades, pavilions and galleries.

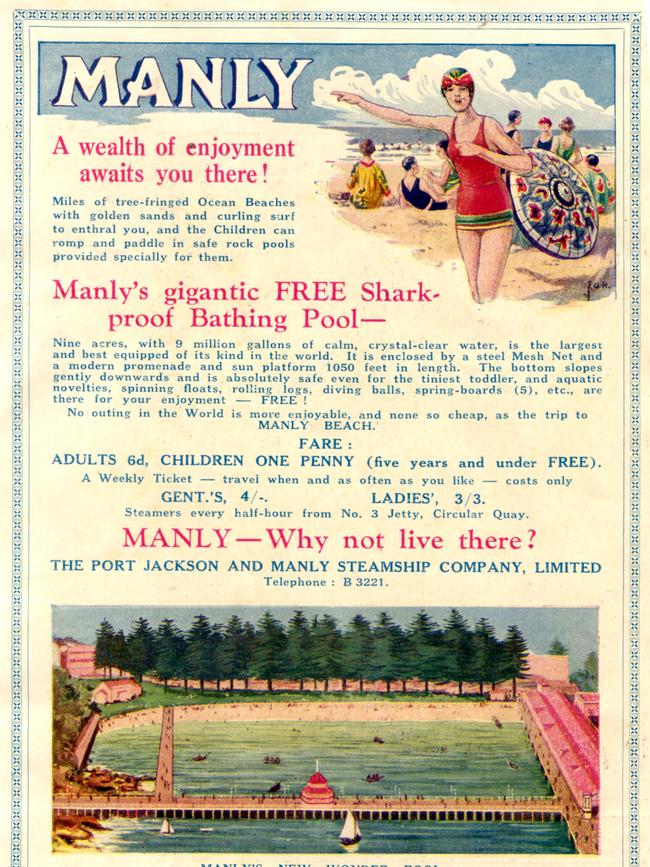

But by far the largest man-made attraction at Manly was the giant, shark-proof pool that was built on the western side of Manly Wharf.

And unlike the other attractions, it was free.

The first the people of Manly heard of the plan to build a giant harbour pool was in one of Sydney’s afternoon tabloids on September 9, 1931, when it was revealed that the Port Jackson and Manly Steam Ship Co was seeking Manly Council’s approval to build the giant pool at its own expense.

But the seeds of the ferry company’s plan appears to have been planted as far back as 1927, when the ferry company’s managing director, Walter Dendy, told fellow directors of the company that Manly’s place as a destination for day-trippers was slipping, especially with regard to bathing facilities, which meant fewer passengers on its ferries.

He recommended that the company build a giant harbour pool next to the wharf, possibly inspired by the Eastern Beach swimming enclosure at Geelong in Victoria.

The proposed new pool was aimed at luring day-trippers on to the company’s vessels.

By 1930, ferry patronage on the harbour was at its peak but the inner-harbour ferry operators knew they would be the big losers when the Sydney Harbour Bridge opened.

Most of the inner-harbour ferry companies were doomed but the Manly ferry company only expected to lose about 20 per cent of its patrons after the bridge opened.

Their confidence was based on the growth over the previous decades of daytime tourism to various harbourside locations, of which Manly was the premier spot.

In 1928, the company had bought two glamorous new ferries, the Curl Curl and Dee Why, which added to the prestige of the Manly fleet and attracted new patrons.

And as the Depression began to take effect, patronage on the Manly ferries actually grew as Sydneysiders discovered the inexpensive pleasure of a ferry trip to Manly and a day at the beach.

There were already several swimming enclosures around the harbour but the Port Jackson company wanted¬ to build what was touted as the largest swimming pool in the country – if not the world – as an added attraction for patrons of its ferries.

But it was not until 1931 that Dendy’s plan came to fruition.

On September 15, 1931, Dendy met Manly mayor Arthur Harcourt and provided more details about the company’s proposal.

Mr Dendy told Ald Harcourt that the proposed pool would be 782 feet (222m) long with a promenade 10 feet (3m) wide, lit up with 20 or more high-candlepower electric lights, in addition to flood-lighting in the pool itself.

Openings on each end of the pool, 75 feet (23m) wide were proposed to be provided, giving access for small motor boats to the beach.

A kiosk for the sale of refreshments would be provided on the promenade and pontoons would be anchored in the pool for use of the bathers.

There was also a plan to build dressing sheds at the western end of the pool, for which a charge would be made for admission but that the pool itself would be free to the public.

Manly Council quickly agreed to the proposal, which wasn’t hard given that it wasn’t going to cost the council anything.

The Manly and District Chamber of Commerce thoroughly endorsed the proposal because it could see that the pool would attract more people to Manly.

The Sydney Harbour Trust agreed to lease the site of the giant pool to the ferry company for £40 per annum.

The ferry company’s plans changed a bit – there would be two promenades, rather than one, a higher one about 3m wide and a lower one about 2m wide, and there would be no access to the beach for small motor boats, which angered the operators of speedboats in the area.

On October 27, 1931, Manly Council gave final approval for the giant pool.

As part of the arrangement, the council would build the dressing pavilion using money lent by the ferry company at 5 per cent per annum.

The proposed pool was not the first pool at the western end of Manly Cove – there had been two earlier pools – one a timber and mesh enclosure known as the Ladies’ Baths to differentiate it from the Men’s Baths on the eastern side of Manly Cove, and a smaller one of steel mesh and naturally-occurring stone that was built after the Ladies’ Baths fell into disrepair.

Designed and built by the ferry company and workers from its base at Kurraba Point, the structure enclosing the pool stretched from Manly Wharf to what is now called Federation Point at the western end of Manly Cove.

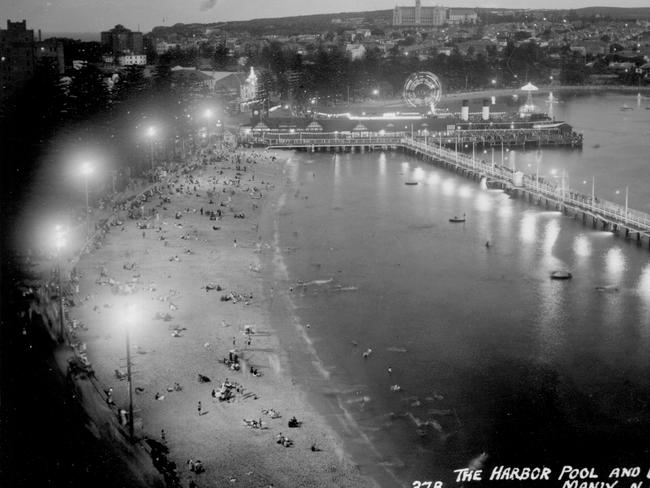

Constructed of north coast hardwoods on turpentine piles, the giant pool built by the ferry company consisted of a promenade 335m long and 3.4m wide, with a 2m wide bathers’ platform at a lower level.

The pool was 275m long, 69m wide at its widest point and up to 6m deep, and contained more than 50 million litres of water.

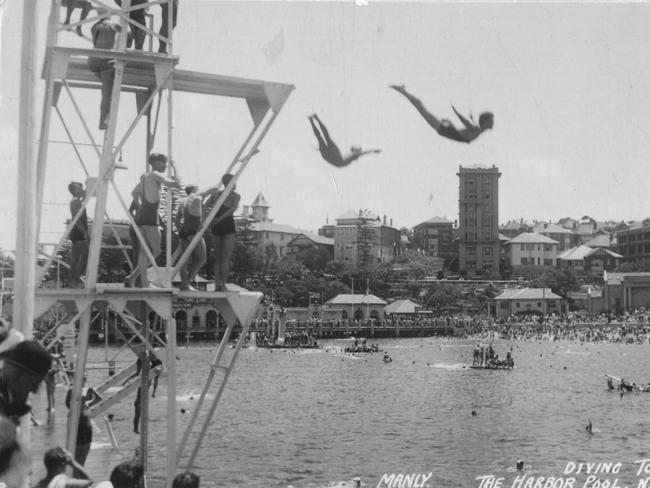

And, as if safe swimming at a comfortable beach was not enough, the pool was also equipped with an array of amusements, including pontoons with slides, water wheels, springboards and even tethered logs designed to buck and roll at the slightest touch, so that mounting them required practise and skills.

Mounted on the promenade were several diving boards at different heights and a water slide more than 15m above water level.

Work on the new pool began on November 9, 1931, and by Christmas Day the pool was shark-proof, although the superstructure was not completed until late January 1932.

In November 1932 the pool was made even more attractive when the ferry company installed floodlights equal to three million candlepower – 50 floodlights on the promenade, 22 on the beach and four underwater.

In June 1933 a dressing pavilion and refreshment rooms were built at the western end of the pool.

Initially Manly Council agreed to build the pavilion with money lent to it by the ferry company, then it was agreed that the ferry company would build the pavilion and that the council would take it over after 12 years, but eventually the construction and ongoing maintenance and management was left to the ferry company with no contribution from the council.

Within two years a quarter of a million people were using the pavilion annually, even though a small charge was made for the use of lockers, showers, toilets and hair dryers.

But admission to the pool remained free.

Above the dressing rooms was a tearoom serving snacks as well as substantial meals and there was an open-air kiosk, the West End, on the beach.

The pool even had its own lifesaving club, the Harbour Pool Life Saving Club, which was formed in 1932 and was quartered in the dressing pavilion, and which held regular carnivals.

And the pool drew the crowds in their thousands – it was shark-proof, it had a broad sandy beach on which to laze, it was close to the wharf and the shops, and it was free.

Over the years numerous amusements were added to the pool, many of which would fail the occupational health and safety laws of today.

An amusement of a different kind was arranged in late 1946 – the former Dutch submarine K XII was put on display between two purpose-built piers that were built on the outside of the pool.

The K-class submarine and its crew had fled Indonesian waters after the Japanese invasion in 1942 and went to Perth, where it was briefly used for anti-submarine training.

It was later brought to Sydney and bought by a syndicate of local businessmen.

In late 1946 an agreement was reached between the syndicate and the Port Jackson and Manly Steamship Company under which the K XII would be berthed on the outer side of the Manly harbour pool and exhibited to the public.

In July 1948, the NSW was pounded by huge seas that caused considerable damage and on July 18 the K XII broke from its berth and crashed through the steel bars that separate bathers in the pool from sharks.

Damage to the harbour pool was estimated at £500.

In June 1949, the NSW coast was again pounded by huge seas and the submarine caused damage to the harbour pool worth £400.

The ferry company was keen to spare its pool from further damage, so it arranged for the K XII to be towed to safer waters further up the harbour.

On June 5 the K XII was towed away from Manly but before the vessels could clear North Harbour, the towline broke and the sub ran aground at Fairlight.

At least the pool was safe.

Then, suddenly, the giant pool was gone – huge waves generated during an intense east coast low weather system that came to be known as the Sygna Storm smashed the grand promenade to pieces on the night of May 24-25, 1974.

The storm took its name from the Sygna, the giant bulk carrier that was driven ashore on Stockton Beach, near Newcastle, and remains the largest ship ever wrecked on the Australian coastline.

Despite occasional calls for the promenade and pool to be rebuilt, they have come to nothing and residents have grown used to the uninterrupted view down the harbour.