The geological highs and lows of the peninsula’s lagoons and the question of their ultimate fate

AMONG the most prominent features of the peninsula landscape are the four lagoons that punctuate the coastline between Port Jackson and Broken Bay.

Manly

Don't miss out on the headlines from Manly. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- The master mariner who was a leading light behind the leading line

- The day timber choked the harbour beaches at Manly

- Bilgola Estate surveyor’s body found after going for a swim

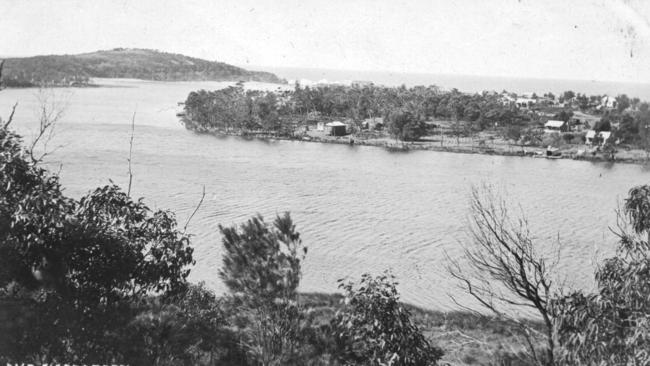

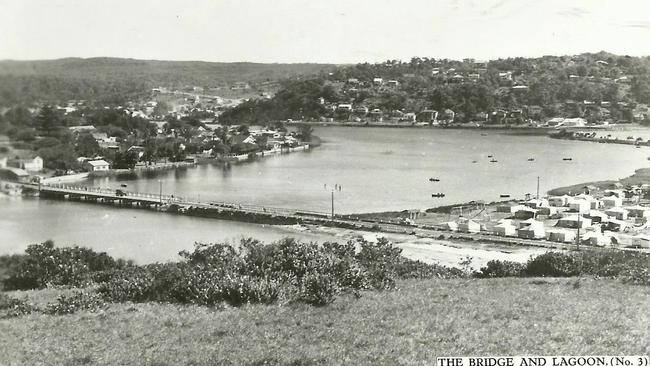

AMONG the most prominent features of the peninsula landscape are the four lagoons – Manly, Curl Curl, Dee Why and Narrabeen – that punctuate the coastline between Port Jackson and Broken Bay.

Picturesque and popular, the lagoons have shaped the development of the area but have also borne the brunt of that development through reclamation, siltation and pollution.

By definition, Broken Bay, Port Jackson and the four lagoons are all estuaries – semi-enclosed bodies of water along the coast where fresh and salt water mix.

The story of these estuaries begins more than 200 million years ago with the birth of the rocks from which the peninsula is formed – a time when Australia was still part of the supercontinent called Gondwana and Sydney lay at the mouth of a broad river basin that was flat and swampy.

About this time, rivers eroding inland mountains began dumping vast amounts of sand, silt and clay into the Sydney Basin.

This process continued for 20-30 million years, during which time layer upon layer of sediment was laid down until the original swamp lay buried hundreds of metres below the surface.

Over geological time, the organic matter in the buried swamp was converted to coal, the sandy sediments were cemented by pressure into sandstone and the finer silt and clay turned in mudstone and shales.

Under tectonic pressure, the supercontinent of Gondwana began to break up and then about 60-80 million years ago, the eastern part of Australia broke away and the Tasman Sea basin was formed. Subsequently, rivers draining the eastern seaboard began eroding the existing pattern of coastal valleys.

As the pattern of the continents changed, so did the climate, driven by the currents of the oceans now separating the drifting continents.

An ice cap formed at the South Pole about 15 million years ago, followed by an ice cap at the North Pole about three million years ago.

From this time, the planet fell subject to periods of glaciation, during which the ice caps expanded and contracted many times, alternately locking up and releasing such vast quantities of water that, at times the sea level rose and fell by up to 120m.

During those times when the sea level was at its lowest, the coastline of Sydney was 15-20km east of its current location and the continental shelf was exposed.

Significantly, rivers from the mountains had further to excavate the valleys through the Sydney Basin just to get to the sea.

This process was repeated many times, interspersed between glacial periods by episodes when the coast was flooded.

The last of the Ice Ages peaked about 20,000 years ago, when the coastal valleys were excavated a final time by the rivers cutting their way to the sea.

As the last Ice Age ended, the sea level rose, slowly flooding the coastal river valleys to form estuaries.

The present sea level was reached about 6500 years ago, although it may briefly have been a few metres higher before stabilising at its present level.

As the sea level rose towards its present level, vast quantities of sand and sediment were transported from the continental shelf, distributed by wind, waves and local currents, and deposited to form beaches, dunes and sand spits.

But not all the early estuaries in the flooded river valleys were identical.

The difference between the estuaries is a function of the geological characteristics of the mouth of each estuary at the time it was formed and the interplay of natural effects like tidal currents, ocean swells and river discharges.

Together these characteristics and natural effects controlled the subsequent sedimentation patterns, salinity regimes, water circulation and, ultimately, the ecology of the present-day lagoons and estuaries.

Port Jackson and Broken Bay are estuaries that combine deep and relatively wide entrances with strong oceanic and tidal influences and significant river discharges, and thus remain open to the sea.

The four peninsula lagoons, however, occupy broad, shallow valleys, across which wind and saves have formed barriers of sand.

They also have narrow, shallow entrances that are mostly blocked by sand shoals and are fed by low-discharge creeks from small catchment areas.

Over geological time, the extent of the sand barriers has increased and the estuaries have become shallower due to sedimentation by sand and mud.

Although Narrabeen Lagoon is usually the exception, today the four peninsula lagoons are often closed to the sea – the power of the ocean to close the mouths of the estuaries with sand is greater than the power of their creek discharges to open them.

Only after heavy rain may the entrances temporarily open when the water level within the lagoon overtops the sand barrier and carves a short-lived channel to the sea.

And the lagoons are still evolving. Over geological time – probably hundreds or thousands of years – the lagoons will naturally fill with sediment from the surrounding catchments and the streams will be confined to narrow channels meandering across a floodplain to the sea.

To make things worse, the edges of some of the lagoons have been “reclaimed” as parks or sports fields by councils using them as landfill sites or by golf clubs draining what were considered swamps.

Unfortunately, it is difficult to determine the rate at which our lagoons are filling up, either by natural or artificial agencies.

Unlike a tree, whose rings mark the passage of the years and the measure of the growth in each year, the sediment on the floor of the lagoons is stirred up by the rich fauna of worms, shellfish and other small marine animals so it never settles into measurable layers.