RMS Austral: The ship that spent six weeks at the bottom of the harbour

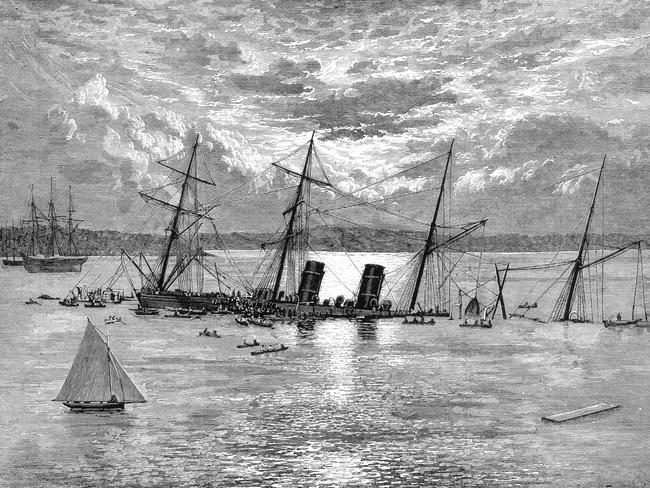

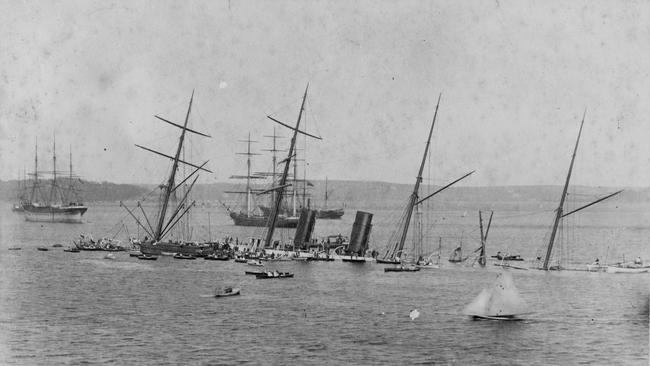

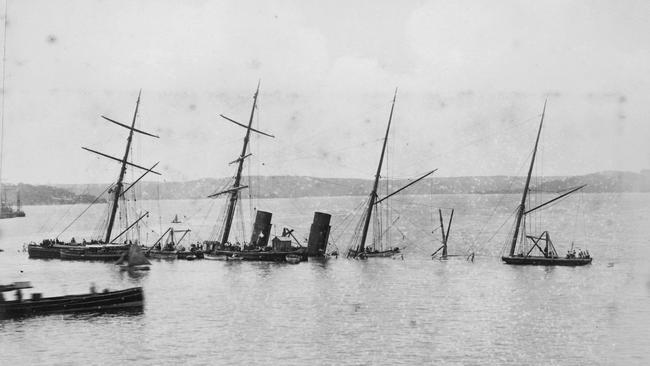

Regular commuters on the Manly ferries get to see some strange sights but rarely as unusual a sight as the commuters of late 1882 and early 1883 got – four ship’s masts and two funnels rising above the surface of the harbour.

Manly

Don't miss out on the headlines from Manly. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Regular commuters on the Manly ferries get to see some strange sights but rarely as unusual a sight as the commuters of late 1882 and early 1883 got – four ship’s masts and two funnels rising above the surface of the harbour.

The masts and funnels belonged to the Austral, a 5580t steamer belonging to the Orient Steam Navigation Co that had been built to service the run between England and Australia.

But how a near-new, state-of-the-art ship came to sink at her mooring off Neutral Bay remained a mystery for several months after her unplanned visit to the bottom of the harbour.

The Austral was built on the River Clyde in Scotland and was launched in December 1881, after which it was fitted out in readiness for its maiden voyage to Australia in May 1882.

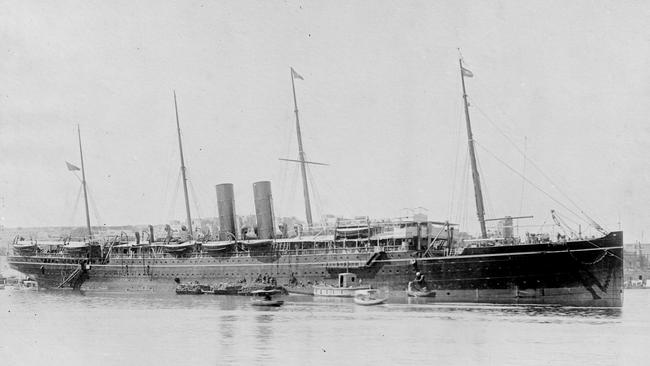

The voyage was uneventful and on its arrival in Sydney, the ship was hailed as a “ship of the age” because it was “different and vastly superior to any of the great vessels which trade between Great Britain and Australia”.

The Austral’s dining room was described as “superior on comfort and on the richness of its decoration to anything the cafes and hotels of Sydney can show”.

But while in Sydney, the ship revealed a hint of what was to come – while being loaded with coal, it developed a moderate list that had no apparent cause.

The ship was eventually trimmed and successfully completed its return to England.

In September 1882, the Austral left England for its second voyage to Sydney, which it reached on November 3.

The Bulli Coal Company’s collier Woonona was contracted to coal the Austral while the latter was berthed at Circular Quay.

The Austral had 15 coaling ports along her hull – eight on the starboard side and seven on the port side – each of which was 1m by 0.7m and about 1.4m above the waterline when the ship was free of cargo.

But after just 230t of coal had been loaded, the Austral suddenly listed to starboard.

It took the crew of the Woonona five hours to remove some cargo and to spread the coal with the Austral to trim the ship, after which it was moved to a mooring off Neutral Bay.

Coaling of the Austral resumed at its mooring at 10pm on November 10.

The coal was loaded at a rate of 25-30t an hour and it wasn’t long before the ship again began to list, although it was not sufficient to cause concern to the crews of the Austral or the Woonona.

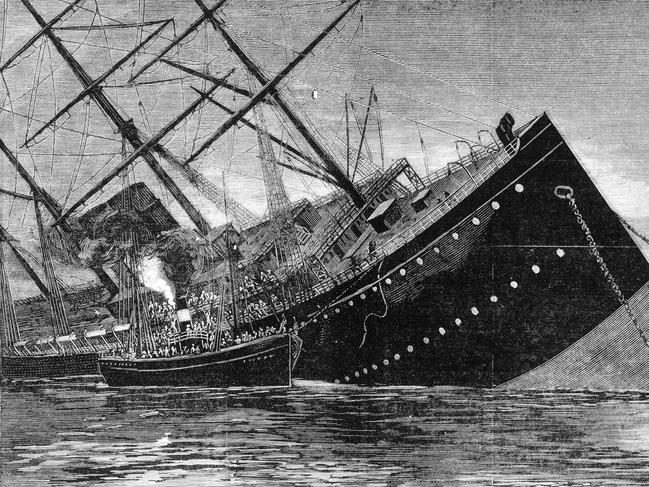

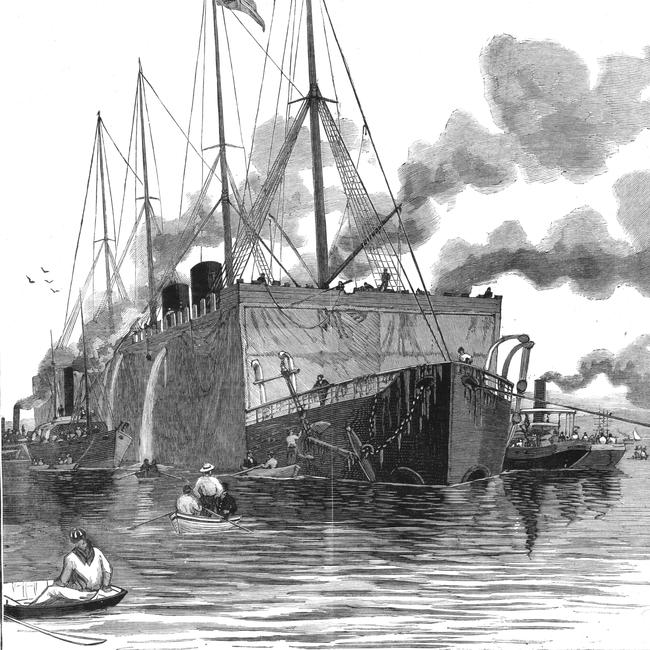

But at 3.50am on November 11, water began gushing into the Austral’s coal bunkers and the ship listed dangerously to starboard, threatening the Woonona.

Just 20 minutes after the first warning, the hull of the Austral disappeared beneath the water’s surface and settled on the bed of the harbour.

Five men were trapped in the Austral and drowned.

The morning light revealed the bizarre sight of the Austral’s four masts and two funnels protruding from the water.

At the coroner’s inquiry into the deaths of the five men, the Austral’s captain, chief engineer and chief officer were found guilty of “a grave error of judgment” for not ensuring any senior officer was in charge during the loading of coal into the ship.

To the dismay of many, however, it was decided the Court of Marine Inquiry into the sinking would be held in London, rather than Sydney.

In the meantime, various experts suggested ways in which the Austral could be raised.

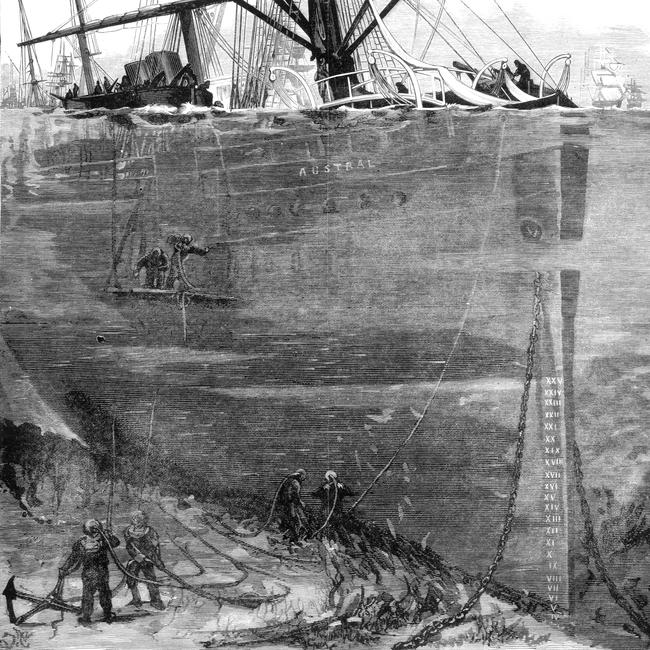

Engineers from England who arrived in Sydney in early January suggested flotation using caissons but local engineers favoured the building of a coffer dam, which called for the sides of the ship to be built up above the surface of the harbour, after which the water would be pumped out of it.

The local engineers won out and a coffer dam was built using a team of 16 divers and more than 80 other men, who effectively increased the height of the ship’s hull by 5m over six weeks.

On February 27, 1883, 10 pumps began pumping water out of the ship at a rate of 280t an hour, until the ship was raised to the surface after four months sitting on the bottom of the harbour, after which she was towed to shallower waters.

Over the next two months the ship’s engines were overhauled and makeshift repairs were carried out.

On May 28, 1883, a sea trial was undertaken to ensure the Austral was fit for the return to England, after which she sailed for home on June 9 seven months after her arrival in Sydney.

Once back in England, the Austral underwent a series of stability tests to determine the cause of her sinking.

At the Court of Marine Inquiry in London, the ship’s designer admitted he had not carried out such tests on the ship because he “did not think it necessary to do so”.

The court found the sinking was the result of a series of small mistakes, including the lack of stability testing, the insufficient number of senior officers on board and the lack of senior officers supervising the coal loading.

As one Sydney newspaper wrote: “The sinking of the magnificent Orient steamer Austral is an occurrence almost without precedence in the annals of maritime history”.

By April 1884, the Austral had been reconditioned and was back in service, and in January 1885 she re-entered Sydney Harbour.

But there was more tragedy to come for the crew of the Austral – in February 1886, three crew members drowned off Dobroyd Head after their whaleboat was capsized by a wave on the bombora.

The search for the men’s bodies continued for a week until Sydneysiders woke to read that a foot and some clothing belonging to one of the crewmen had been found inside a shark that had been caught the same day the crewmen had drowned but was not cut open until a week later.

Over the following years the Austral made another 50 voyages between England and Australia before she was finally was sold to ship-breakers in Genoa in late 1903.