Edward Eyre of Manly: Australia’s first paid lifeguard saved many lives

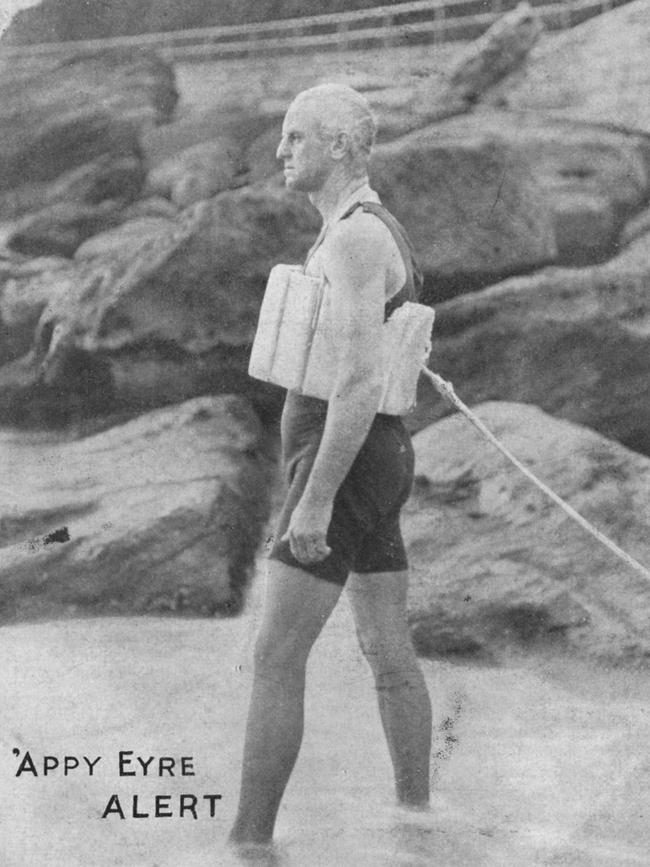

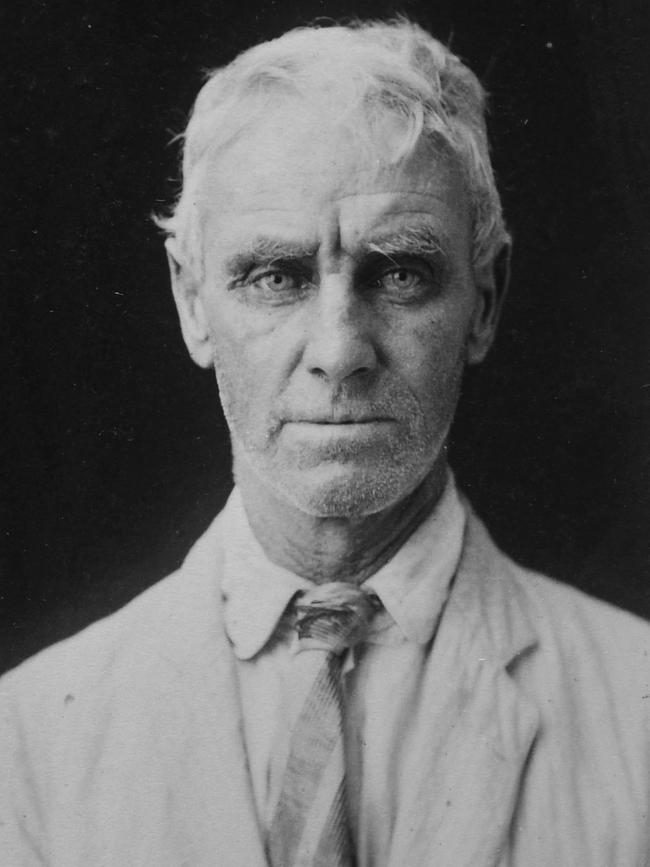

He was the first paid lifeguard in Australia – possibly the world – and is credited with saving more than 100 lives but Edward ‘Happy’ Eyre lived a complex life.

Manly

Don't miss out on the headlines from Manly. Followed categories will be added to My News.

He was the first paid lifeguard in Australia – possibly the world – and is credited with saving more than 100 lives but Edward ‘Happy’ Eyre lived a complex life.

And if his personal life was anything to go by, his nickname – Happy, or sometimes ‘Appy – might have been ironic, rather than descriptive.

Eyre also surrounded himself with mystery by apparently lying about his birthplace, his mother’s name and his age.

When he enlisted in the Australian Army in July 1915, he wrote that he had been born in Auckland and was 44 years and seven months old at the time, meaning he had been born in late 1870 or early 1871.

When he died in July 1938, his death certificate indicated he was 69 at the time of death, meaning he would have been born in 1869.

His death certificate, for which his son Frank supplied the information, also indicated he had been born in Auckland and was the son of William and Mary Eyre.

But there is no record of an Edward Eyre being born in New Zealand between 1865 and 1875.

There was, however, an Edward Eyre born in the NSW town of Sofala in 1866, the son of William and Sarah Eyre.

It wasn’t unusual for men to lie about their age when they enlisted, especially if they were under or over the legal ages of enlistment, but why he might have lied about his birthplace and his mother’s name is a mystery.

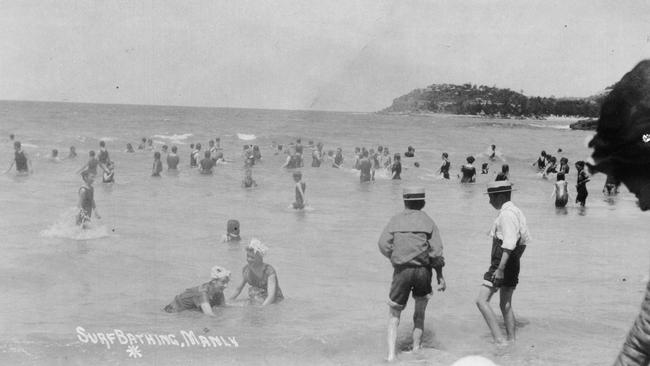

What is certain about Edward Eyre is that he saved the lives of many people during his tenure as a paid lifeguard at Manly and North Steyne in the early 1900s.

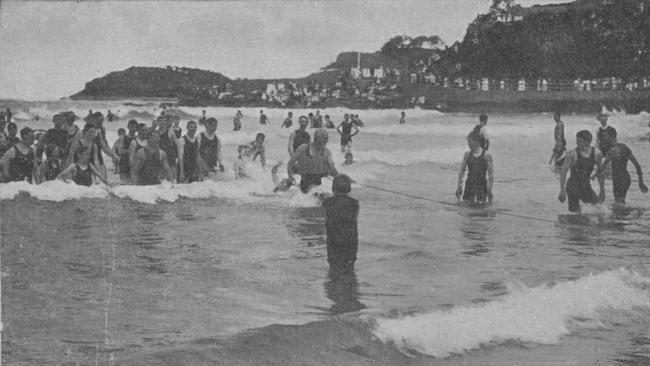

And his lifesaving skills were certainly needed.

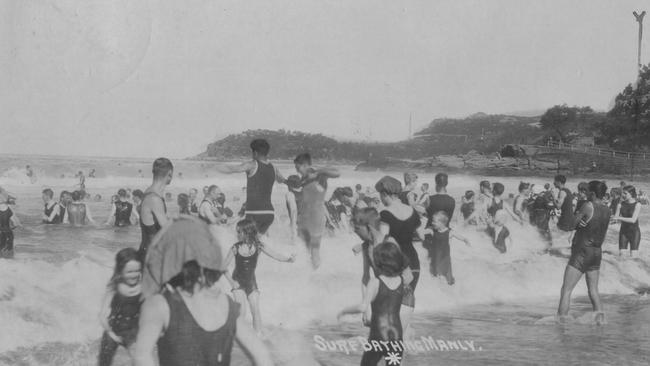

In October 1902, Randwick Council overturned its ban on daylight bathing, becoming the first council in NSW to do so.

Thirteen months later, in November 1903, Manly Council overturned its ban on daylight bathing, becoming the second council in NSW to do so.

But bathers had been ignoring the bans for ages – and frequently getting into trouble in the surf, due mainly to inexperience.

In March 1903, a man was washed out from Manly Beach and was in danger of drowning.

Members of the Sly family – local fishermen who kept their boat on the beach at Fairy Bower – immediately put to sea and succeeded in reaching the man and bringing him to shore.

From that rescue was born the idea of stationing a boat off the beach on busy days to rescue bathers who were washed out in rips.

In September 1903, a public meeting in Manly Town Hall agreed that a boat should be stationed off Manly Beach on busy days and that members of the Sly family should be engaged.

The Slys’ boat began patrolling off Manly Beach on October 1, 1903, paid for by public subscription, and quickly proved its worth.

But at the start of the 1904-05 bathing season, there were insufficient funds to pay the Sly family, so the Manly branch of the Life Saving Society, supported by donations, engaged Edward Eyre as a professional lifeguard.

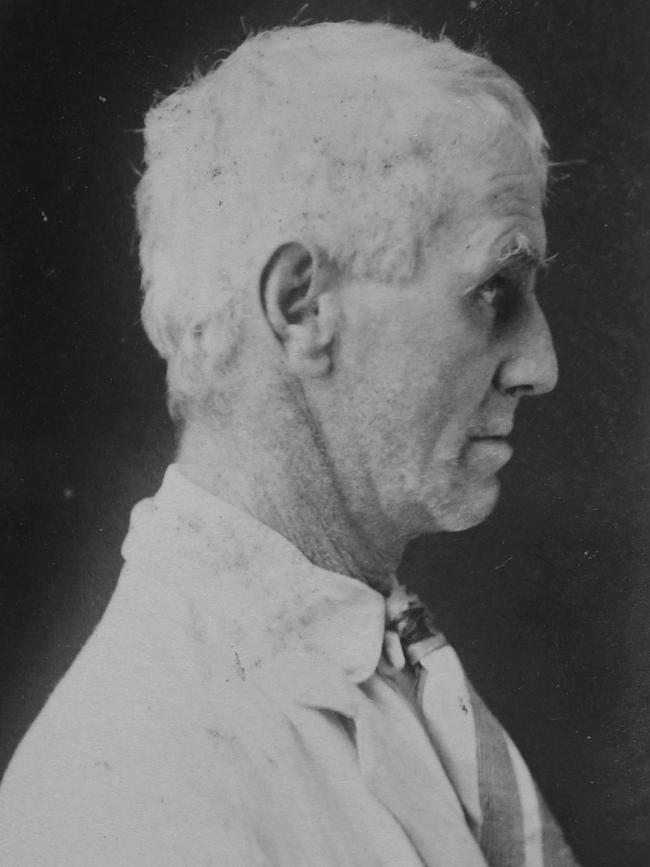

Eyre was certainly a fit man – he had played rugby union for the Pirates, Glebe, North Sydney and Manly, represented NSW against Victoria in 1894, and made the trip to New Zealand with the NSW team that year, which was undefeated on the tour.

In the only Test played in 1894 at Christchurch, Eyre scored the winning try for NSW as the tourists beat New Zealand 8-6.

A newspaper reported in 1906 that it was while playing football that Eyre earned the nickname “Happy”.

After being engaged by the Manly branch of the Life Saving Society, Eyre almost immediately proved his worth – on November 18, 1904, he swam out with a lifeline to a man who was in trouble and brought him back to the shore.

On January 4, 1905, Eyre was involved in another rescue when a man named Fenwick got into trouble in the surf and a man named Smith swam to his aid and was able to keep Fenwick afloat.

Eyre went out with a lifeline and brought both men back to shore.

But not everyone could be saved – on January 11, 1905, a 13-year-old boy entered the surf while a heavy sea was running.

Attempts by Eyre and another man to save him failed.

On January 3, 1906, Eyre rescued a boy and a man who had gone to the boy’s aid and on February 5, 1906, Eyre was one of three men who went to the rescue of two women and a child who got into trouble in the surf at Manly and brought them safely to shore.

But the public subscriptions the Manly branch of the Life Saving Society were insufficient to pay Eyre a regular wage, so Manly Council decided at the start of the 1907-08 season to appoint Eyre as the beach attendant for Manly Beach.

On December 26, 1907, Eyre was one of several men involved in the rescue of two men who got into difficulties in the surf and on New Year’s Day, 1908, he was one of five men who rescue seven men in trouble in the surf at Manly.

In May 15, 1908, Eyre rescued two women who had got into difficulties in the surf.

But by 1911, Eyre was on the outer with Manly Council.

He was also facing competition from other lifeguards for the limited number of positions, so in March 1911 his workload was reduced to two days a week as Jack Reynolds and Norman Roberts took his place as the main council lifeguards.

The council probably went cold on Eyre as a result of his appearance in court upon being charged in July 1910 with assaulting his wife Margaret.

It wasn’t Eyre’s first appearance in court, although in the first instance it was after he was assaulted by a woman who either poked him in the eye or hit him over the head with an umbrella, depending on which newspaper you were reading. The woman was found guilty.

But while he was the victim in that court case, in every subsequent case he was either the offender or the alleged offender.

In September 1907 he was found guilty of using of using indecent language and given the choice of seven days in jail or of paying a fine. He paid the fine.

In April 1909 he was found guilty of deserting his wife Margaret and fined.

In July 1910 Eyre was found guilty of assaulting his wife and given the choice of spending seven days in jail or of paying a fine. He paid the fine.

In December 1910 he was found guilty of possessing an unregistered rifle and given the choice of spending seven days in jail or of paying a fine. He paid the fine.

In March 1911 – a just as he was seeking to keep his job with Manly Council – Eyre was found guilty of using obscene language and given the choice of spending 14 days in jail or of paying a fine. He paid the fine.

In August 1912 Eyre was charged with assaulting his wife Margaret with an iron bar.

He told the court that he was sick of coming home and finding his wife drinking with her friends, with her not sending their children to school and with not bringing his meals down to him while he was working.

Although the couple’s 12-year-old daughter corroborated her mother’s claim that she had been assaulted, Eyre was acquitted.

In December 1912 he was found guilty of using obscene language and given the choice of spending 14 days in jail or of paying a fine. He paid the fine.

In January he was found guilty of two counts of using insulting words and given the choice of spending 21 days in jail or of paying a fine. He paid the fine.

In July 1914 Eyre was found guilty of riotous behaviour and given the choice of spending seven days in jail or of paying a fine. He paid the fine.

In February 1915 he was found guilty of assaulting a man and inflicting grievous bodily harm and this time there was no choice – he was sentenced to one month of hard labour.

During the trial, Eyre told the court that he had saved 140 lives during his time as a lifeguard.

In July 1915 Edward Eyre enlisted for service in World War I.

Two of Eyre’s successors as lifeguards at Manly – Jack Reynolds and Norman Roberts – had already enlisted and both had already lost their lives.

Norman Roberts was killed in action on April 25, 1915 = the first day of the Anzac landing at Gallipoli – and was buried at Quinn’s Post.

Jack Reynolds died of wounds received in action at Gallipoli and was buried in Chatby Military Cemetery in Alexandria.

Interviewed after enlisting, Eyre told one Sydney newspaper: “I’m going out to revenge Jack Reynolds and Norman Roberts.”

After arriving in Egypt, Eyre sustained an injury to his right shoulder, was invalided back to Australia and was discharged in July 1916.

Back in Australia, Eyre was soon back in legal trouble.

In November 1920, he was found guilty of offensive behaviour and fined.

The following month he was found guilty of threatening behaviour and given the choice of spending two months in jail or of paying a fine. He paid the fine.

Four days later Eyre was found guilty of assault and of using indecent behaviour and given the choice of spending 21 days in jail or of paying a fine. He paid the fine.

In March 1921 he was found guilty of riotous behaviour and of threatening behaviour and given the choice of spending one month in jail with hard labour of paying a fine. He paid the fine.

Eyre died in July 1938 of cancer, leaving his wife Margaret, five daughters and a son.

He was buried in the Catholic section of Manly Cemetery, where he lies in an unmarked grave.

Whatever the reason behind his nickname and despite his checkered history, Edward Eyre earned a special niche in the history of Manly and of surf lifesaving on the northern beaches.