One of Sydney’s oldest cemeteries reveals the fascinating secrets buried in the city’s past

The history of one of Sydney’s oldest cemeteries reveals storiesof unsolved child murders, jilted brides, Australia’s Titanic and much more.

Inner West

Don't miss out on the headlines from Inner West. Followed categories will be added to My News.

It’s the final resting place for around 18,000 former Sydneysiders and Camperdown Cemetery has almost as many stories to tell.

The Newtown landmark, near St Stephen’s church, was opened in 1848 after the city’s original cemeteries near Town Hall and Central stations filled up and the city started spreading away from the harbour.

RELATED: SYDNEY’S HIDDEN STORIES

RELATED VIDEO: GHOST WITH TASTE FOR RED WINE VISITS SYDNEY PUB

RELATED: ARCHIVES REVEAL STORY OF SYDNEY’S PLAGUE

The land, including what is now Camperdown Memorial Rest Park, was granted to Governor Bligh before later being subdivided.

Even now, the popular park still has bodies buried underneath.

The site is due for a clean up after receiving a state government grant to help restore some of the stones, particularly the pauper’s grave dotted around the outer edge, after consistent acts of vandalism.

Jenna Weston, chair of the Camperdown Cemetery Trust and an archaeologist at the Australian Museum, said the history of the site revealed many stories.

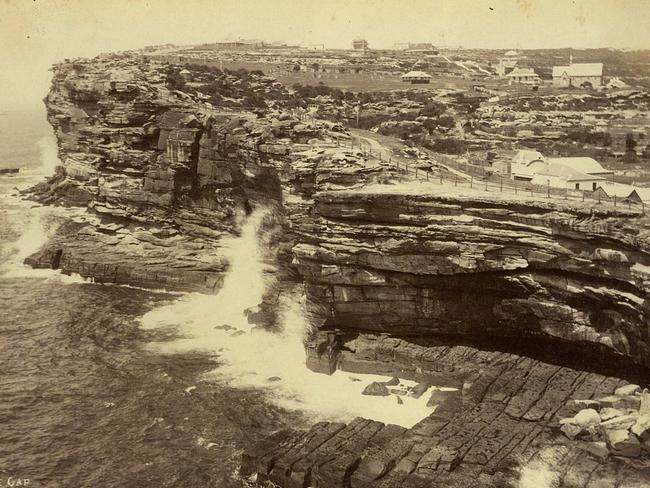

A mass grave at Camperdown Cemetery holds the remains of the 121 lives lost when The Dunbar ran aground in the Gap in 1857.

Ms Weston described The Dunbar as “Australia’s Titanic.”

The 202 foot vessel was predominantly a passenger ship and arrived in Sydney Harbour on the evening of August 20, 81 days after leaving England.

Some believe the ship’s captain mistook the Gap for the entrance to the harbour when tacking towards the heads.

“It happened on a dark and stormy night in the middle of winter,” Ms Weston said of the wreck.

“There was only one survivor who was tossed up on to a ledge on the Gap wall and scrambled up before the waves could take him out again. He stayed there the for two days and a night until someone finally saw him and rescued him.”

That survivor was crewman James Johnson, from Marrickville. In a miraculous tale of survival, Mr Johnson clung on to the cliff face with his fingertips before climbing as high as he could until the morning of August 22 when he was rescued.

It is estimated that 20,000 mourners gathered on George St for the funeral procession on August 24 before the remains of the Dunbar’s passengers and crew were buried.

Eliza Donnithorpe was born in to wealth as the daughter of James Donnithorne, who, among other prestigious jobs, was master of the Mint in Calcutta.

Her mother and two sisters died early of cholera before James and Eliza moved from India in 1836 and settled in Cambridge Hall on King Street, between Georgina and Fitzroy Streets.

Ms Weston said that Eliza was an independent-minded young woman who dismissed all her father’s potential suitors before settling on a man of her own — thought to be called George Cuthbertson — four years after her father’s death.

The wedding, a grand society affair featuring Sydney’s leading socialites of the time, was set to take place in 1856 at nearby St Stephen’s Church, with Eliza aged about thirty.

For reasons that have never become apparent, George never showed up and was never seen again, leaving Eliza heartbroken.

Ms Weston said this had a profound effect on Eliza.

“There are various theories but she was convinced he would come back so she refused to leave the house at any moment and basically became a recluse,” Ms Weston said.

“She kept the door on the chain in case he came in the middle of the night and wouldn’t let them clear the wedding breakfast.

“She died 60 years of later and had been in that place the rest of the night.”

Ms Weston added that some believe she never removed her wedding dress. Her life is often cited as an inspiration for Miss Havisham, the famous spinster from Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations (1861).

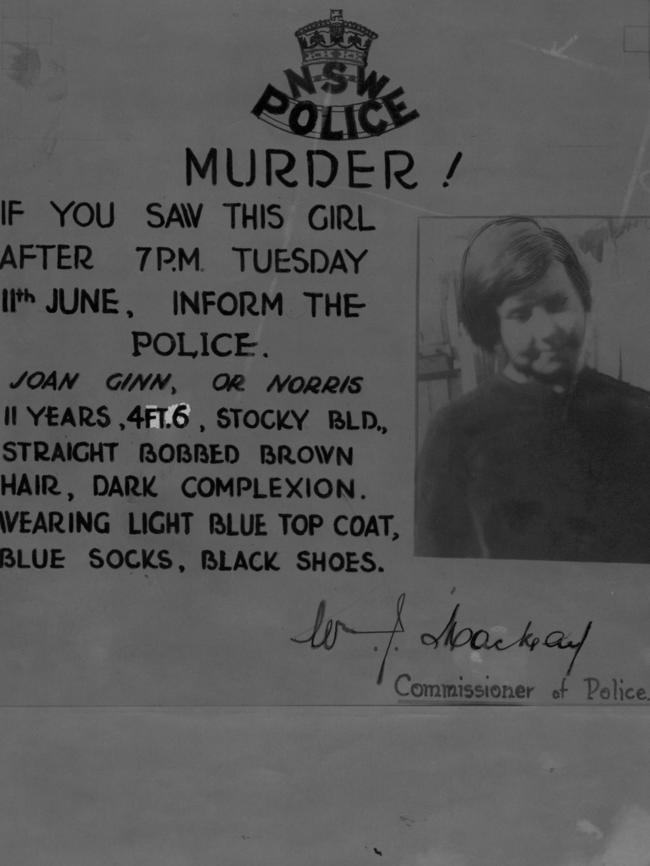

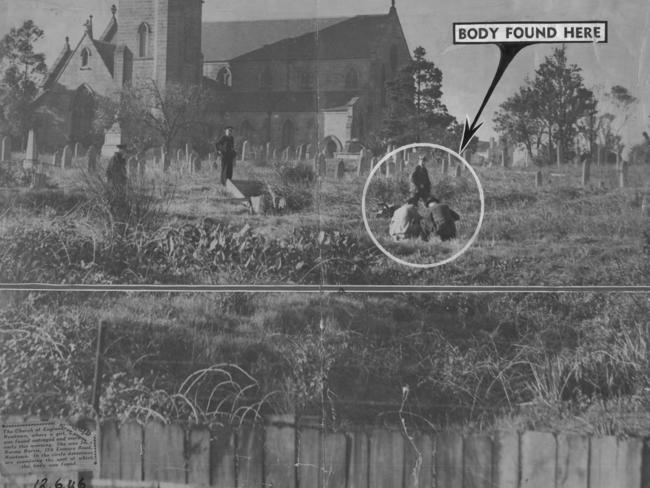

Camperdown Cemetery made headlines in 1946 when the body of missing schoolgirl Joan Norma Ginn was discovered on June 12.

The 11-year-old had been sent out by her mother to buy some bread but never returned.

The body was recovered the next day, with Joan’s yellow cardigan reversed to look like a straitjacket. There was evidence of sexual assault.

Three men confessed to the murder in November of the same year but police dismissed these confessions and the murder remained unsolved.

The murder prompted a rethink on the layout of the cemetery with four acres sectioned off for the cemetery and the turned in to Camperdown Memorial Rest Park.

■ Tours of Camperdown Cemetery take place on the first Sunday of the month

■ The tour costs $10, email tours@neac.com.au for more