Superintendent Swilks hangs up his hat after 44 years

WHEN Superintendent Dave Swilks is piped out of the Wyong Police Station today, it will not only mark the end of a decorated 44-year career, but the end of an era.

Central Coast

Don't miss out on the headlines from Central Coast. Followed categories will be added to My News.

WHEN Superintendent Dave Swilks is piped out of the Wyong Police Station today, it will not only mark the end of a decorated 44-year career, but the end of an era — an era of a certain type of old-school copper who was, arguably, the best police commissioner we never had.

From the Bega schoolgirl murders and the ill-fated 1998 Sydney to Hobart, to the killing of Amanda Carter and the grounding of the Pasha Bulker, Supt Swilks has had an exclusive access-all-areas pass to some of the state’s most seminal moments.

And, of course, there was the time he locked up Mr Music from Romper Room.

The 61-year-old will be piped out of the Wyong Police Station for the last time today after he hangs up his hat on a career spanning almost four-and-a-half decades.

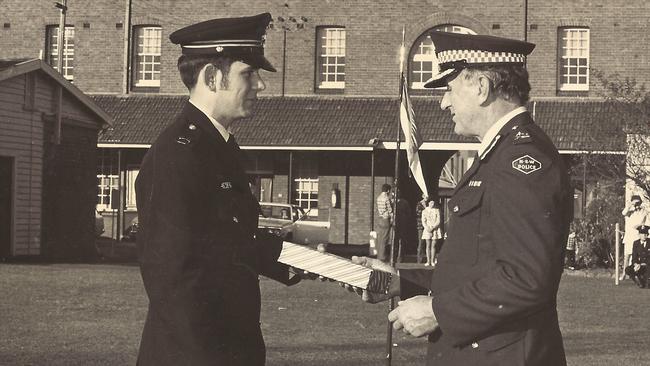

Supt Swilks joined the now disbanded police cadets program in 1972 when he was just 16.

Back then the cadets program unashamedly borrowed a lot of its manifesto from Hitler's Youth in its approach of taking teenagers and moulding them into a certain type of men.

“There was only 5000 police when I joined,” he said. Today there are nearly 16,500 and growing.

After his two-year cadetship, he spent the next 12 months dealing with “vagrants and alcoholics” at Redfern before spending three years in what was then the internal affairs branch.

Supt Swilks came from a police family. His father was a copper, as was his brother, and he would later marry a policewoman.

He was posted to Morisset in the late 1970s.

“Domestic violence was not an issue (back then), hotels closed at 10pm, so it was unusual to have a job after midnight,” he said.

But in an era before breath-testing, he said crashes and fatal accidents more than compensated for a “less violent” time.

He then went to the rescue squad at Newcastle, but left after two years because “it was more of an extraction of bodies than saving people”.

It was at Toronto in 1981 where he managed to talk down a crazed man armed with an automatic weapon, for which he received his first of many decorations — a Commissioner’s Commendation for Courage.

It didn’t go so well in 1988 at Morisset where he was shot in the leg, but his composure under a hail of bullets earned him a coveted Valour Award and an Australian Bravery Decoration.

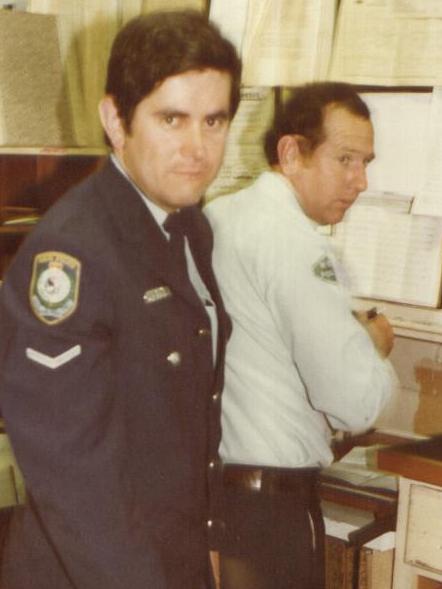

In 1986 he was promoted to Detective and spent time in the vice and gaming squad at Hamilton as a plain clothes officer.

“It was interesting, there were some dodgy elements I had to deal with,” he said.

This long before the Wood Royal Commission, a time when the public perception was that some police were a law unto themselves and corruption was rife.

For a young man of unquestionable integrity, it was a difficult period in Supt Swilks’ career to navigate.

“It was very much ... you didn’t know who to trust at senior levels,” he said.

“There was talk about graft, (but) people knew I was in internal affairs. It’s certainly not that way now.”

Of the hundreds of arrests Supt Swilks made over the years, some have stood out for obvious reasons.

“I locked up Mr Music from Romper Room,” he said of the arrest in 1991.

“He broke into a person’s house and the person was a solicitor ... he got a fine.”

He was a senior sergeant at Bega during the 1998 Sydney to Hobart tragedy, when dozens of stricken yachts and the bodies of six sailors were brought in to Eden.

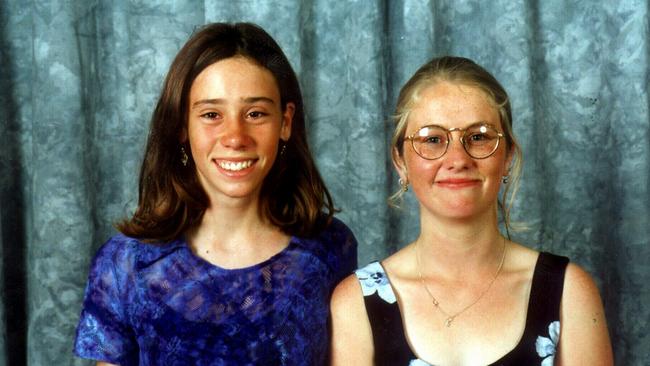

The year before, 14-year-old Lauren Margaret Barry and 16-year-old Nichole Emma Collins were abducted, raped and murdered before their bodies were found dumped in bushland across the border in Victoria.

“My wife took the first report,” he said.

“They were going to visit some friends that were camping. It was quite a brilliant piece of police work by the detectives. They traced it back from a red TV set they moved for the girls (to get in the car).”

Supt Swilks was at the helm of the Waratah command in Newcastle when the Pasha Bulker ran aground in the June 2007 super storm and he co-ordinated the disaster response as the local emergency operations controller.

Supt Swilks became the commander of Tuggerah Lakes in March 2008 and opened the command’s headquarters in 2012.

More recently, he said, he was proud of his detectives in securing a conviction against Ricardo Dasilva for the murder of popular Wyong High School teacher Amanda Carter six years after her death.

“I’ve been fortunate in some regards,” Supt Swilks said.

“I will miss the people, it makes the job, and I won’t miss the deadlines. It’s my intention not to get a mobile phone.”

“I GUESS HE DIDN’T WANT POLICE TO KILL HIM AFTER ALL”

AS THE bullet from the high-powered automatic weapon tore through his inner thigh and punctured a hole in his trousers, police officer Dave Swilks didn’t have time to think how a hastily thrown-together plan had gone so horribly wrong.

Any higher and his four-month-old son would have been his only child.

Superintendent Swilks — then a senior constable — and his sergeant had left a junior officer in the paddy wagon, thinking it would be the safest place from the crazed gunman.

Meanwhile the sergeant — a Vietnam War veteran — had circled around to flank the assailant as Supt Swilks tried to talk him into dropping the gun.

It was 3.30pm on October 6, 1988. Supt Swilks was 33.

Out of a career spanning 44 years, this is the moment forever burned into his mind.

It was right on shift changeover time at the eight-man Morisset Police Station when they got a call about a bloke down at the pool firing shots in the air.

The man had just found out his sister had been sexually assaulted and was out for some kind of misguided revenge on anyone or anything.

Supt Swilks and his two colleagues were armed with .38-calibre Smith and Wesson revolvers — essentially glorified “pop guns” — up against an automatic weapon and a man “who basically wanted police to kill him”.

“Thirty-eight calibre were very slow bullets,” Supt Swilks said. “They only travel 138 feet (42m) per second. You could nearly outrun them.”

The first shots tore through the police van, forcing the junior officer to take cover behind it as the gunman turned his attention on Supt Swilks.

It was years before Port Arthur, Snowtown and Ivan Milat would forever alter Australia’s policing psyche.

It was long before Bear Cats and tactical response units could be summoned for immediate backup.

It was before negotiators and protracted stand-offs that would get analysed forensically for months afterwards.

It was a time when the frontline police were the ones who turned up and got the job done.

Eventually, the bullets stopped whizzing by Supt Swilks’ head and the sergeant managed to take a shot as the gunman went to reload.

The bullet struck him in the arm and travelled up his skin. Back then, it was not unheard of for crooks to be shot five or six times by the small lead bullets and keep returning fire.

“It knocked the wind out of him and I went up and arrested him,” Supt Swilks said.

“He wasn’t even bleeding. I was bleeding more from where the bullet grazed my leg. I don’t smoke, but I gave him a cigarette.

“I guess he didn’t want police to kill him after all.”

The man served 12 years in jail.

“He sent me a Christmas card afterwards but I threw it in the bin, I didn’t want to know,” he said.

“I never had to draw my firearm again.”

But it took two years before “it felt like the physical weight lifted from my chest” and he got over it.

The Central Coast’s most decorated officer’s career did not start there.

Nor did it begin seven years earlier in 1981 in hauntingly similar circumstances, back at his hoodoo station, Morisset, when a man armed with a single automatic weapon was trying to get into a house.

On that tense occasion, with guns drawn, Swilks did manage to talk him down with out a shot being fired.

Reflecting on his distinguished career Swilks said the more things changed, the more the heart of policing never faltered.

“The same attitude (is there), the same constant, is to go out and catch crooks and make a difference in the community,” he said.