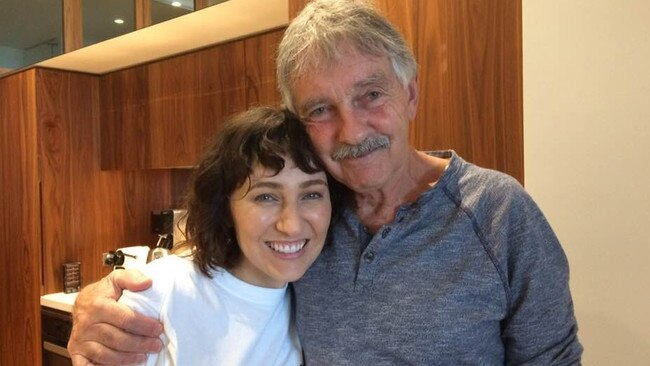

Gerda Foster reflects on running programs for inmates around regional NSW

Once a glamorous nightclub jazz singer, Gerda Foster has spent the last 38 years working in jails and stresses the importance of ‘play’ for inmates as part of their rehabilitation. Here’s her story.

The Bowral News

Don't miss out on the headlines from The Bowral News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Once a glamorous nightclub jazz singer, Gerda Foster has spent the last 38 years working in jails and stresses the importance of ‘play’ for inmates as part of their rehabilitation.

The Southern Highlands local - now Goulburn Correctional Centre Services and Programs Team Leader - said she landed in the industry by “pure chance”.

Her Miles Franklin award-winning husband David Foster was working at Berrima Gaol at the time, teaching writing to inmates, and needed a leading lady for a pantomime.

“I was a singer in another life and became the leading lady for a play inside the jail – we did eight performances for preschool kids,” Mrs Foster said.

The education officer then told her she would “do well in the system” and offered her a job.

“She said ‘the guys feel very comfortable with you, it’s unusual to find such a good mix’,” Mrs Foster said.

Mrs Foster’s warmness and enthusiasm for life is immediately clear, and she takes that same energy to work, often wearing bright colours to the jail because “you need to wear bright clothes to such a dull place”.

Having started out teaching healthy lifestyle to the male inmates at Berrima, the Bundanoon local then ran yoga, mediation and nutrition classes to help them be “more healthy in mind, body and spirit”, which was influenced by her passion for mindfulness and life on the farm.

“We were growing our own food for a long time which we wrote a book about (A Year of Slow Food),” Mrs Foster said.

“I had eight children for the school holidays because between my husband and I, we have two marriages and eight children, so we couldn't afford to feed them unless we had a cow, chicken and lots of food.”

Over the years she worked in the community as a program organiser across Young, Wagga Wagga, Bowral and Goulburn, with both men and women. She later progressed to a drug and alcohol program worker.

She credits her creative ideas at work to trying to keep her kids busy during the holidays.

“We had no money, no phone, no television, so the kids had to be entertained or taught how to entertain themselves, so that's how I started in group work,” Mrs Foster said.

“I do a lot of fun things, I'm a big believer in being playful, getting people to laugh. I wouldn't want to come to a group and be bored out of mind.”

Mrs Foster has also done talks on crime prevention beginning in childhood, and the importance of play in children and adults too.

That’s why she’s introduced ‘play’ as part of the prison program - getting inmates to do arts and crafts, mindfulness, aerobics, dancing, even jumping through muddy puddles.

“There’s been lots of research to suggest that people learn best when they are at a place of wellbeing – they don’t learn when they’re bored or angry.”

One of her career highlights was organising a drug and alcohol free dance party with the women inmates in Berrima.

“I just wanted to show the girls that they could dance to a DJ without using drugs or alcohol,” Mrs Foster said.

“Lifeline lent us clothes and we had a whole room full of second-hand clothes so the girls could choose an outfit to wear.

“Some girls said ‘I've never danced sober and straight, I didn’t think I had it in me’.”

She’s witnessed people on “all sorts of drugs,” and spoke of the change in drug use over the years.

“About 80 per cent of offenders have got drugs and alcohol in their offending,” Mrs Foster said.

“In the 80’s/90’s it was heroin, then cocaine and now ice which is a really insidious drug because it’s lowered the moral values due to desperation, even in jail.

“I used to be alone doing aerobics with 25 inmates in maximum security and I knew I was safe. Now I don't know how that would work.

“The trouble with that drug is that they don’t sleep for a week or 10 days, hallucinate and then they are no longer in the real world.”

Mrs Foster gave an example of an inmate whose offending was spurred by drugs and alcohol.

“There was one guy in one of my aggression classes who was there because he had come out of jail, he was working, was happy, had a few drinks, argued with his girlfriend, went and got some ice and attacked a stranger in the street,” Mrs Foster said.

“Now this poor kid is in a wheelchair for the rest of his life. It was a random attack – which is not unknown – and he has to live with that for the rest of his life in terms of what he did when he was under the influence of that drug.”

She stressed the importance of addressing trauma in the justice system for offending to be mitigated.

“We’ve got to deal with people’s traumas, you can put all the drug dealers in jail but there will be another one that’ll take their place,” Mrs Foster said.

She also spoke of how staff can be “severely traumatised as well”, and relayed her own experience.

“A long time ago when I burnt out working three jobs because there were no staff, I realised I saw 25 people die through being murdered when they got out, murdered in jail, overdoses and suicides,” Mrs Foster said.

“Twenty-five people that I’d been quite close to and trusted me and told me their stories. I hadn’t had a chance to address that sort of trauma.”

When asked where the system needs improving, Mrs Foster spoke of how inmates are reintegrated back into society.

“The other day, someone in maximum security (Goulburn Correctional Centre) yelled out to one of the officers and said ‘I’m getting out tomorrow, I’ve got no money and I’ve got nowhere to live’,” Mrs Foster said.

“And all we could do is give him some phone numbers and say ‘if you do get bail you can ring them’.”

However Mrs Foster said “there's been a huge shift” since she started working in the system.

“Officers used to never speak to inmates, only address them by their surnames or MIN number (inmate number),” Mrs Foster said.

“There was such a divide between officers and inmates – now that has changed radically and you will often see them joking with each other.

“The officers who get trained now do what’s called ‘motivational interactions’, where they’ll speak to an inmate for two to three minutes and are trained on how to make that conversation meaningful.”

She mentioned some of the great programs they run at Goulburn Correctional Centre which are aimed at improving the wellbeing of inmates and their families.

One program called ‘mini dads’ involves inmates designing a cover for a children’s book they get to choose, then recording themselves reading that book out loud, which will be sent in the form of a CD as part of the bundle.

“There’s been reports of inmates saying to the facilitators that once their children have received their package, they are much more eager to speak to them,” Mrs Foster said.

“That’s one way to get the offenders to change their ways – to get them to think about how important their fathering is.”

Despite working in the system for 38 years (even as a criminologist at one point) Mrs Foster is not thinking of retirement.

“I think I’ve been a very helpful force in allowing the inmates to find themselves and hopefully improve their lives, which has been a passion of mine,” Mrs Foster said.

“And at the moment I'm here and still enjoying it.”