Architect Phillip Cox is behind many of Sydney’s most treasured buildings but even he doesn’t love them all

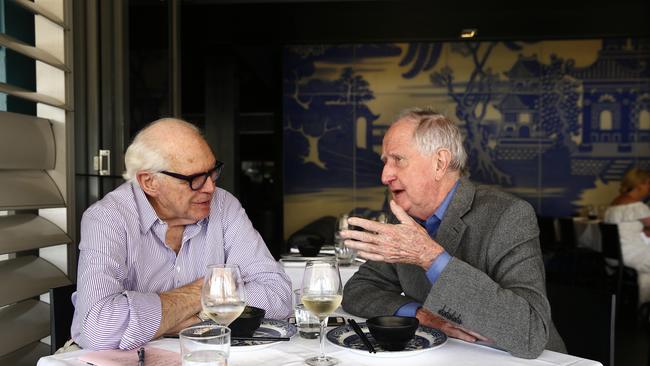

Dr Phillip Cox AO worked on a raft of buildings including the Sydney Football Stadium and the Star Casino. Some he adores, others not so much, discovers Leo Schofield.

Local

Don't miss out on the headlines from Local. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- Maggie Tabberer refelcts on triumph, tragedy, Helmut Newton and the love of family

- Peter Rix: The secret behind Marcia Hines’ career longevity

Over the past two centuries, members of the Cox family have figured prominently in the history of New South Wales.

Readers will be spared genealogical minutiae, of which there is an abundance, and simply know that William Cox, the begetter of the eponymous antipodean dynasty, was born, educated and married in Dorset, England. He served in the British army rising to the rank of Lieutenant. Appointed paymaster to the New South Wales Corps, he sailed to Australia with his wife and four sons in 1799.

Social distinction would have been apparent on the voyage out, as the handful of free settlers on board were vastly outnumbered by 160 convicts housed in miserable conditions on the lower decks.

A red coat was a distinct advantage and could be a passport to riches. Although the fortunes to be made in New South Wales were relatively small, they were substantial for any officer like Cox who, in 1800, purchased 40 hectares of farm land west of Sydney, resigned from the army, became principal magistrate at Hawkesbury and was also responsible for erecting a number of government buildings. In 1814, Lachlan Macquarie, our most enlightened Governor, approved Cox’s offer of superintending and directing the working party that built the road across the Blue Mountains, between Sydney and Bathurst.

I suggest to one of Cox’s descendants, the celebrated architect Philip Cox, that he could be considered representative of colonial aristocracy. He pooh-poohs the idea.

“Think about Lieutenant Paterson.” he says, citing another colourful historical figure of the colonial era. “He made a much more impressive contribution. He travelled up and down to Tasmania, acted as Lieutenant Governor after Bligh was dismissed, got involved in a dispute with Macarthur and fought a duel with him He was a botanist and created a large nursery at what is now the inner west suburb of Petersham, introduced peaches into Australia and, died on a ship heading back to England.”

Cox’s knowledge of history is impressive. As is his passion for architecture, even in its rudimentary forms.

Educated at Shore in North Sydney, he became interested in architecture while still at school. He recalls that “Shore had a fine art department. A number of students went on to become leading artists,” he notes, citing two in particular, Tim Storrier and Gary Shead.

Early in his architectural career he collaborated with the photographer Wes Stacey on a series of magnificent publications celebrating our vernacular buildings, woolsheds, rude timber buildings and bridges. But his career and fame rest on some spectacular examples of contemporary architecture that managed to be both practical and beautiful.

Stacey once described Cox as “an international architectural success whose strength and focus is on management of work”.

But he is more than that. Put simply, he is Australia’s most successful, most prolific and most admired architect. Iconic buildings around the world are testament to his skills. These are predominantly public buildings, and include Sydney Convention Centre, the Australian National Maritime Museum, Sir John Monash Centre in Villers Bretonneux, France, the Rod Laver Arena in Melbourne and the Sydney Football Stadium at Moore Park.

Cox’s confident, patrician hand is identifiable in exhibition centres, city office towers, school and colleges, community centres, bridges. And — dare one utter the word to him? — stadium.

Apparently a confidentiality agreement precludes any exhaustive comment on the wilful destruction of his Sydney Football Stadium which lies in ruins in Moore Park.

But gradually he opens up. Apropos the demolition, he expresses an opinion: “Very sad. It was a perfectly good building,”

I ask if it’s true that he’s been invited to design its replacement. “They haven’t asked me. They’ve asked the firm.

“There a philosophical difference between what was, and what the government now, wanted.” The idea of a refurbishment arose during a period of Labor government. The new Liberal government had different ideas.

“The firm proposed that there should be no corporate boxes, no segregation. It seated 45,000 and felt very democratic.”

He noted that “the new stadium will have 5000 fewer seats”.

It is also to have five restaurants, cocktail lounges, spaces for networking “It’s all about socialising, not about the game.”

“In the UK,” he continues, “you buy a pie and a beer and watch the game. You don’t go to a stadium for fine dining. You go for the aura of a stadium. You might go to a pub afterwards but, basically, you’re there to watch the game.”

He has a comment, too, on aesthetics. “It’s taller. Looks like a wedding cake. Terrible intrusion on Paddington.”

We move to a happier subject — Bermagui. Continuing the family tradition of significant land acquisition, Cox and a small group of like-minded friends, 40 years ago bought 80 hectares of land here, both as a conservation exercise and as a private retreat.

“While New South Wales people tended to drift north in search of escape, there was very little drift south,” explains Cox. “The far south coast was pretty much the playground of the Melbourne rich.”

“Bermagui is a beautiful place. It has been largely forgotten and un subdivided,” muses Cox. “From a selfish point of view I’m happy with that.”

“It was famous for fishing. It had a brief moment of fame when the American writer and big game fisherman Zane Grey visited there in the 1930s.

There used to be a cooperative, too, and most of the fish was sent to Sydney, but with growing awareness of a need for improved conservation practices, the number of licenses reduced. And they used to win international prizes for butter cheese. Then all that stopped.”

Cox embarked on a program of rehabilitation of the land and creating a private retreat and a beautiful natural garden. That he appears to have succeeded triumphantly is evidenced in An Australian Garden (Thames and Hudson) which he’s written, a chronicle of his creation of a remarkable series of spaces, a reimagining of how the landscape might have once looked.

I’d met Cox a number of times before this lunch and thought him haughty and conscious of his family’s social standing. Roughly 60 years ago I visited the sites of the three great Cox mansions in Mulgoa, Wimborne, destroyed by fire but remembered for a Hardy Wilson drawing of the pigeon house, Glenmore, now serving as a golf club, and the glorious Fernhill, still miraculously intact. The daddy of them all, though, is Clarendon, near Launceston, built by members of the family who settled in Tasmania. In the event, Cox proved the jolliest of luncheon companions and an inexhaustible source of gossip.

“I thought of you as a member of the colonial aristocracy,” I said as we parted.

“My parents thought they were,” he quipped. “The family came out here, acquired all this land and did nothing.”

“When my father asked my grandfather how he saw himself, the old man replied: ‘As an English gentleman’.”

Leo’s lunch at China Doll took place just before the government’s COVID-19 restrictions came into force.

Caption

Leo Schofield with architect Dr Philip Cox at China Doll in WoolloomooloPicture: John Appleyard.