What life under the ‘new’ Taliban will be like: Freedoms v restrictions

As Afghanistan and the world wait to see what truly lies in the hearts of the ‘new’ Taliban, deep divisions within its own ranks mean there is no clear agreement on a vision for the future.

World

Don't miss out on the headlines from World. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Why is Hamid Karzai still alive? The first president of Afghanistan to take office after the Taliban’s 2001 fall, not only still breathes, he still walks free. Not imprisoned. Not mercilessly tortured. Indeed, the Taliban have brought him to their table, sitting face-to-face to negotiate a new Afghanistan.

It doesn’t make sense.

Everyone trying now to read the tea leaves is left wondering: What will life under the Taliban look like?

So, why Karzai? Is it because he’s Pashtun, the same ethnicity as the Taliban itself? Or that, in a previous life, he represented the Taliban regime in its infancy on the international stage?

Or is it something different about this Taliban?

It’s a worthy question. For within its answer may lie clues to the true nature of this renewed Taliban.

A nature that has not yet had the time to expose itself. But, before long, it will. For all the world to see.

Who is this Taliban? What new calculation have they made? And how long will any of this last if, in fact, any of it is even remotely real? Is it a strategic ruse. Playing for time. Awaiting an unknown and nightmarish hour. They cannot be trusted. And no one does.

As US National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan says, when it comes to the Taliban it’s not about trust, it’s about verification.

For now, divining what truly dwells in the Taliban’s hearts is little more than a morbid geopolitical parlour game. Yet the stakes in this dread charade could not be higher.

For the Afghans themselves, for the government soldiers who fought and killed Taliban. For the Afghan women and girls who fear being cast once more into a medieval pit of hell and servitude.

For now, at least, the Taliban proclaim their intention to be rational actors on the world stage.

Its spokesman Zabihullah Mujahid said – albeit to withering global scepticism – the regime will be “positively different” from its brutal forebear that ruled from 1996 until its fiery demise in 2001.

“The Islamic Emirate, after freedom of this nation, is not going to (seek) revenge (on) anybody, we don’t have any grudges against anybody,” he added.

He promised free speech by a free media, so long as it doesn’t work against national values. Also, no safe havens for terrorists.

On the most searing of issues for the international community, the plight of women and girls, he declared: “The Islamic Emirate is committed to the rights of women within the framework of Sharia.”

Many of the right words, notwithstanding the spectre of Sharia Law, but will the right actions follow?

It must be said, female oppression is not exclusively a Taliban product. Outside of Kabul women are encased in a traditional culture that predates Islam.

As they say, Kabul is “not” Afghanistan; it’s an island of relative advancement alone in an ocean of deeply conservative and honour-bound rural provinces. Child brides, face coverings, domestic violence were norms well before the Taliban’s rise in the mid-1990s.

But if women’s freedoms can be a barometer for the other re-branded Taliban principles, then there is already an early assessment. Adherence to these assurances will be, to understate it, “patchy”.

We’ve witnessed a preview of this for women and girls. While the central leadership ordains girls can return to school – reportedly distributing head scarves at some school gates – and encourages women to resume their employment, the abeyance has been unsurprisingly uneven.

In one city, for example, girls were welcomed back to class. In another, reports of girls’ schools being looted and shuttered quickly countered the narrative.

This is what life under this Taliban will be like. Freedoms given by one hand, restrictions returned by another, but neither universally applied.

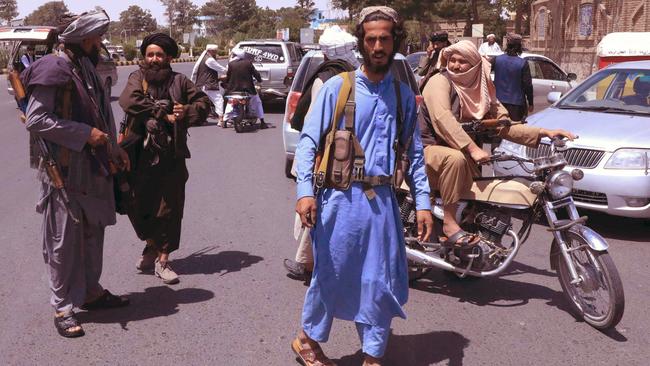

While the Taliban has robust national command and control, as evidenced by the well-orchestrated offensives across the country, it is not one, coherent body. It is littered with factions. Local customs, district power centres or varying inclinations within the movement can, often, prevail over broader proclamations.

Afghanistan itself is not one country. It is a loose assembly of tribes. Bound together only by geography and artificial borders. No central government in Kabul can ever, has ever, been able to project power to the disparate rural domains. Afghanistan is governed village by village, valley by valley. No matter who holds power.

As a source in talks with the insurgents remarked, the Taliban will always be the Taliban. But what does that mean today? Even the Taliban does not know.

There are deep schisms within the Taliban.

As one Afghan dealing with them put it, while the “fat-bellied technocrat Taliban” have their, loosely, more moderate vision, it’s not a notion shared by the foot soldiers who’ve spent two decades in firefights with Americans, or perhaps Australians, and seen their comrades die. For them, the Old Ways are the way of the future.

For them all, however, is a burning new imperative. They need to govern. And to do so competently or risk losing support from the villagers and provide fuel for armed tribal resistance.

Within the Taliban’s upper echelons there is wide acknowledgment of this dilemma. For the shadow government they’ve maintained in sanctuary in Pakistan has not had to actually govern.

Should electricity fail to flow, roads be repaired, law and order preserved, or health care offered then instability is certain.

The Taliban need the bureaucrats who have been keeping the country running for the past two decades.

Fighters going door-to-door identifying government workers is ominous. It poses a dire threat for US military translators, but it is also reflects their desperate need for all of those workers who keep the proverbial trains running on time.

What’s precarious for the Taliban is that Afghanistan is not the same country it once ruled. New generations have grown up on the internet, with smart phones and improved education. Expectations have changed. Aspirations have heightened or, as one negotiator put it, people’s “goals” have changed with new ambitions.

Top Taliban recognise this. Some acknowledge it as a “headache” they must now confront.

That alone signals an evolution of thought that’s quietly occurred in their years in the wilderness.

Perhaps the most influential Taliban of all is Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar, its co-founder and de facto leader.

Calling for “humility” among the triumphant fighters, he said: “Now comes the test. Now, it’s about how we serve and secure our people and ensure their future.”

Though captured in a CIA-driven raid, then imprisoned for eight years in Pakistan, he was released in 2018 and led peace negotiations with the Americans. Today many view him as a “moderate” they hope will temper the Taliban’s brutal excesses of the past.

Externally, there are few pressures to bring to bear. But foremost among them is leveraging the Taliban’s stated desire for international recognition and an end to their pariah status.

They seek a veneer of respectability because they want, and need, the international aid money to resume. The country’s economy relies heavily on the roughly $US4 billion per year it currently receives. It is the government’s lifeblood.

Afghanistan’s central bank chief says the supply of US dollars in hand is “close to zero”. Tweeting that of the country’s $US9 billion reserve, most of it is outside of the country. And the bulk of it has been frozen by the US Treasury Department.

The EU has also suspended millions in aid, but is open to releasing it if the Taliban meets certain human-rights standards.

Whether those incentives will be enough to soften the Taliban’s edge is yet to be seen.

They could go it alone, but the appetite for returning to a sanction-riddled and cash-starved scenario is low. Only the most ardent of hardliners will advocate such a course.

So, the Taliban will, realistically, require American support and that of the United Nations. It’s a bracing thought. Their only alternative – apart from drug trafficking and revenue

from taxing trade at its flourishing border crossings – may be support from its long-time sponsor, some say master, Pakistan.

And there are also the world’s authoritarian states. From Iran to Moscow to China who care little for the fate of Afghanistan’s people. Beijing, in particular, is eager for Afghanistan’s potential deposits of rare earth elements and a railway across Central Asia, may contemplate backing even an unpalatable regime.

All over the world those watching these tumultuous weeks can only have grim foreboding.

Let us hope, after four decades of war, a normalisation of relations with much of the world will hold more appeal for the Taliban than a violent, ruthless new oppression.