What a Kamala Harris presidency would mean for Australia if she wins the US election in November

With barely 100 days to campaign Kamala Harris has bolted out of the blocks, as experts reveal what it would mean for Australia if she wins the US election.

World

Don't miss out on the headlines from World. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The US presidential election race is usually a political ultra-marathon, not a sprint.

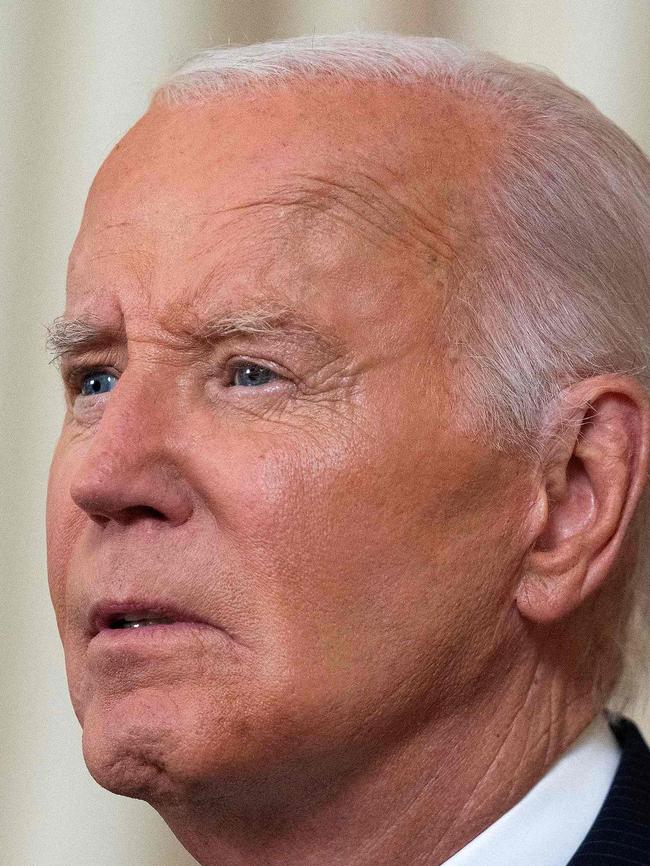

By the time Americans cast their ballots on November 5, it will have been 721 days since Donald Trump announced his bid to return to the White House. As for Kamala Harris, Joe Biden’s decision to quit in the final stretch has given her barely 100 days to campaign.

She has bolted out of the blocks, breaking fundraising records, crisscrossing battleground states and lighting up social media. If she is going to hit the finish line first, however, she will soon need to answer a vital question: what would her presidency mean for the US?

Ms Harris’s candidacy is so far defined by what she is not: the frail and unpopular Biden, nor the convicted felon Trump. Having avoided a competitive candidate selection process, she is not armed with a tested policy platform of her own, and as the sitting Vice President, she is tied to the Biden administration’s historical record and its agenda for the next six months.

While Ms Harris will sketch out more of her vision in the days ahead, these constraints mean it is unlikely to radically depart from her predecessor’s plan, at least in substance if not in rhetoric. And that, experts say, is good news for Australia.

If elected, Ms Harris will enter the Oval Office with more foreign policy experience than any president in the past three decades apart from Mr Biden, a 52-year Washington DC veteran.

The Vice President has travelled to 21 countries and met more than 150 world leaders, a schedule that has focused heavily on the Indo-Pacific region and featured multiple encounters with her “dear friend” Anthony Albanese. White House officials say she has been an integral figure in developing the administration’s China policy and putting it into action.

Charles Edel, the Australia chair at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies, says Mr Harris has “acquitted herself quite well” in deputising for Mr Biden in the Indo-Pacific.

“I would expect if she were to win, you would see broad continuity of President Biden’s approach to the Indo-Pacific: privileging allies and partners, assuming that strategic competition is the norm with China, ensuring that strategic competition doesn’t veer into catastrophe, and continuing dialogue with the Chinese,” he says.

Mr Edel says this includes maintaining and bolstering initiatives involving Australia, such as the AUKUS defence pact and the Quad security dialogue. The Prime Minister expressed similar confidence this week as he described Ms Harris as an “outstanding candidate” – a notable endorsement compared to his cautious language about Mr Trump’s potential return.

When Ms Harris hosted a lunch for Mr Albanese in Washington DC during his state visit last October, she spoke glowingly of the US-Australia alliance, saying that “although a great distance may separate us, the bond of friendship draws us forever closer.”

She also made a point of highlighting her personal bond with Mr Albanese, built on their common commitment to upholding Indigenous and LGTBQ+ rights and tackling the “existential crisis” of climate change. Mr Edel says this bodes well for a continuation of Mr Albanese and Mr Biden’s effort to expand the alliance to clean energy and critical minerals co-operation.

Ms Harris has also been in lock-step with Mr Biden on other foreign policy priorities, such as defending Ukraine. She briefed President Volodymyr Zelensky on US intelligence on the imminent Russian invasion in 2022, and when she became the presumptive Democratic presidential nominee, her first call to a foreign leader was to Zelensky’s chief of staff.

But the conflict in the Middle East could be a point of difference. While Ms Harris has not broken with Mr Biden, she has more aggressively condemned Israel’s actions in Gaza, a stance that may harden during the campaign given her party’s vulnerability with Arab-American voters.

When Mr Biden and Ms Harris met separately with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, after the President abandoned his re-election bid, it was Ms Harris who spoke publicly and said of the suffering in Gaza: “We cannot look away in the face of these tragedies … I will not be silent.”

Hundreds of Democratic Party foreign policy heavyweights have endorsed Ms Harris as “the best qualified person to lead our nation as Commander-in-Chief”. Her most critical foreign policy task, however, is also her most glaring political weakness.

She was tapped by Mr Biden to tackle the root causes of migration in Central America but was unable to stop the record influx of illegal immigrants across the US-Mexico border.

This week, rather than ignoring Mr Trump’s potent attack on her as the failed “border tsar”, Ms Harris tried to up-end the debate by blaming him for blocking Mr Biden’s bipartisan laws to tighten the border – a reform package she vowed to implement if she was elected.

In terms of her domestic agenda, the early signs are that she will look to improve the sales pitch of Mr Biden’s record, while pushing on with other policies he has been unable to land.

Paid parental leave, expanded child tax credits, more affordable childcare and caps on rental increases loom as centrepieces of a family-first response to the cost of living crunch.

“Building up the middle class will be a defining goal of my presidency,” Ms Harris said in her first address as the presidential candidate, “because we here know, when our middle class is strong, America is strong.”

It was a line straight from Mr Biden’s stump speech. Backed by forward-looking ideas, Ms Harris’s hope is that it will cut through to voters while he wears the blame for the inflation pain.

Ms Harris is also a fierce advocate for the right to abortion, an issue that has ignited voters since the Supreme Court overturned the landmark Roe v. Wade decision, but which the Irish Catholic Mr Biden has struggled to prosecute as effectively. He rarely even says the word.

And while Mr Trump tries to frame Ms Harris as a “radical-left lunatic”, she is backing away from her more progressive views, such as banning the unconventional oil and gas extraction method of fracking that has spurred record production in more conservative states.

It is a cynical but pragmatic move that reflects an essential truth: the best vision for Ms Harris to take to the American people is the one that convinces them to vote for her to deliver it.