Democracy without sausage: US elections explained

Ahead of the US election in November, here’s a look at how different voting in the land of the free really is compared to Australia.

US Election

Don't miss out on the headlines from US Election. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Like sisters from different misters, or brothers from other mothers, Australia and America look a bit similar sometimes.

Both are vast federations of states and territories; both are English-speaking democracies dominated by two main political parties; and both have capital cities ensconced in their own discrete boundaries.

But look at what’s on TV, or listen to the way people talk, or watch the way they behave, and the differences in the DNA become immediately apparent.

And so it is with voting. It’s a fundamental right in both countries, but with characteristics that are unique to each.

As America heads to the polls on Tuesday, November 5, here’s a look at how different voting in the land of the free really is.

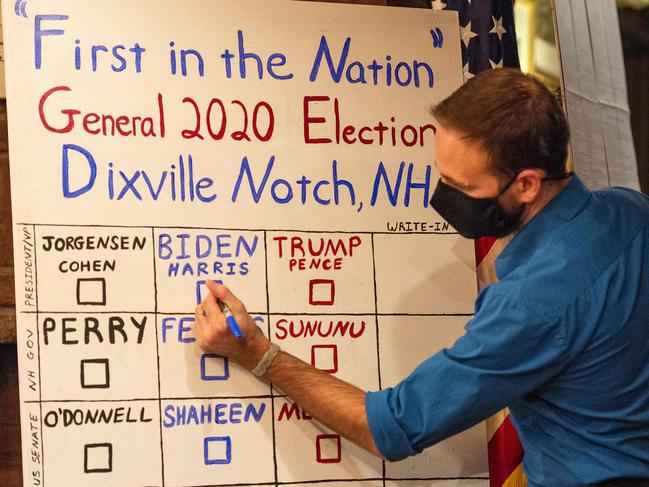

Fifty different elections

In Australia, federal elections are administered by the Australian Electoral Commission (AEC), a central, independent statutory authority that ensures the conditions for voting are identical in each state.

But in the US, it’s “50 different jurisdictions doing their own thing,” said Professor Benjamin Reilly, visiting fellow with the United States Studies Centre at the University of Sydney.

Arrangements can vary widely. Polling times, arrangements for voting early or via post, ID requirements, how votes are lodged and how they are counted; all these things are set at the state rather than federal level.

While the bulk of American states still use a first-past-the-post model to count votes, two states (Alaska and Maine) use the system common to Australian voters, called proportional representation (referred to as ranked-choice voting in the US). This means voters rank candidates according to the preference in which they would like to see them elected, as opposed to just backing one candidate. Nevada might also move to this system if a ballot measure is carried on November 5.

Registering vs Enrolling

Australia is one of a hodgepodge, almost random collection of countries where voting is compulsory. (Belgium, Brazil, Chile, Singapore and Turkey are some of the others.) Voter enrolments are managed by the AEC.

America doesn’t require its citizens to vote or even register to do so, and as a result, many don’t. While the turnout rate of eligible electors is up on what it was in the Twentieth Century, and reached a record high in 2020, one in three voters still stayed home.

Scholarly types have reflected on the effect of compulsory voting, suggesting it keeps politics roughly balanced in the centre of popular opinion.

In the US, voter registration is handled by each state, and you must be registered in order to vote (although North Dakota is an exception to this; in that state you can just rock up on election day, so long as you show valid identification).

There are lots of other variations between the states; in some you must register at least 30 days before polling day, while in Connecticut, Colorado and some other places, you can register on election day, and then vote. In many parts of the country you can register online, but in Texas and Wyoming and other states, you have to register via post.

It’s also common – but not mandatory, and not the case in all states – to register your party affiliation. In some states, that party affiliation means you get the right to vote in the primaries for that party (that’s the process by which the Democrats and the Republicans decide who is going to be their nominee for president).

Another seeming oddity: by registering as a voter for a particular party, you’re not obliged to vote for that party at all. You can still choose as you please at the voting booth.

What’s involved in being a voter?

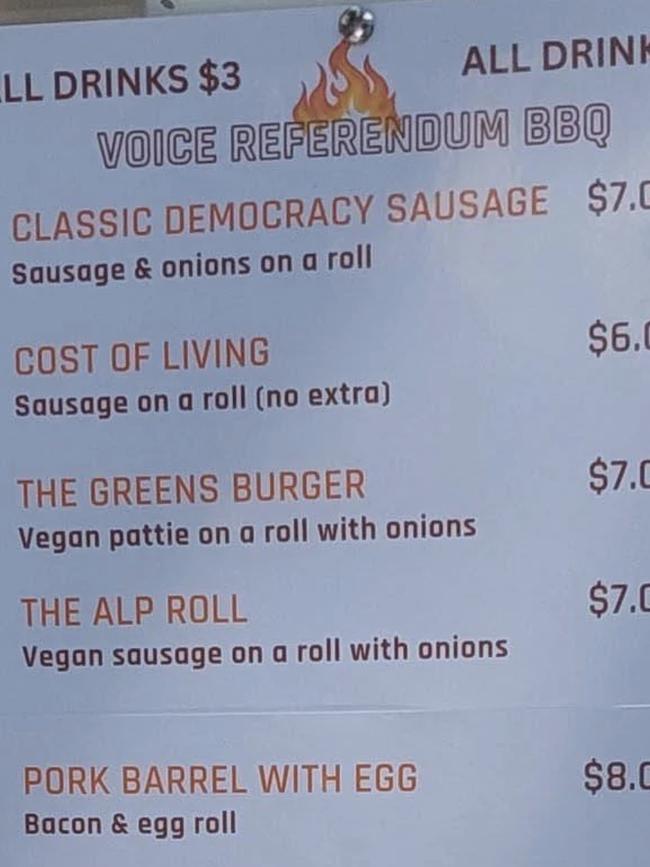

Australians have an undeniable affection for election days. They’re held on Saturdays, so nobody’s too rushed; the queues are usually short; once you break through the cordon of volunteers thrusting how-to-vote cards in your hands, you’re left in peace; early voting is pretty easy if you need it; the process is relatively simple; and best of all, there’s almost always a cake stall or barbecue, so you can get yourself a “democracy sausage” and turn it into an outing.

American elections are not quite so gala. They’re held on Tuesdays, queues can be long, and the process can be time-consuming.

Besides voting for a President and a Vice President on November 5, voters in many states will also be asked to vote for candidates in the House of Representatives and the Senate, as well as local publicly elected officials, as well as “initiative ballots” – referendums or plebiscites on contentious issues.

The result can be dozens of individual decisions, said Prof Reilly, “so there’s absolutely a fatigue issue involved”.

And the process of voting varies as well – some states use paper ballots and other opt for machines.

Who gets to vote?

The vote is open to all US citizens aged 18 and up, but beyond that, it depends on what state you’re in. Some states allow permanent residents to vote; other don’t.

The rules around convicted felons also vary massively; in some states a conviction will mean your right to vote is taken away forever, and in others it’s just for the duration of a sentence. It can also depend on the sort of crime. (Despite being a convicted felon, Donald Trump will be eligible to vote in Florida on election day.)

Some states also prevent people under guardianship – the legal control mechanism Britney Spears was under for 13 years – from voting.

All states offer some form of postal voting but the rules differ: some states send out a ballot paper to all registered voters, while in Delaware and Indiana you need a valid reason to vote via mail.

And on election day, the rules around the ID you need to show are different from state to state.

Over the past few decades, Prof Reilly, said, the Republicans have “typically been trying to restrict the franchise in different ways, restrict the ability to vote easily, and the Democrats have typically been trying to expand it”.

These have been for political as well as ideological reasons for both parties, he said – but more recently things have changed.

“The Republicans under Trump have increasingly been going after the less-educated, more working class segment of American society, and they’re precisely the people who don’t have all the documentation that’s needed [to vote]. So there’s been a bit of a turn now from the Republicans, where they were initially very opposed to things like mail voting but they’re now in many cases more open to it,” Prof Reilly said.

The voting blocs

Given it’s not a legal requirement, voter drives are a huge part of US elections. Energising community interest around candidates is key.

In 2024, US election watchers will be looking at Kamala Harris’s campaign to see if more women and more people of colour turn out to vote for her.

“There is a black vote very strongly connected to the Democratic Party,” said Prof Reilly. “There is also an Asian American vote, less wedded to either of the parties. And there is also an ethnic cross racial vote – and Harris is emblematic of the fact that lots of Americans are not just one thing or another.”

Another tactic parties sometime use is to develop or support “ballot initiatives” – state referendums that may further incentivise voting, which can come from local legislatures, or from citizens themselves (although it depends on the state).

About half the states have no ballot initiatives planned for November 5, while others have a lot. Arizona is already planning to put 11 different questions to electors.

The initiatives cover a bewildering array of topics, but hot-button issues like abortion, gun control and the legalisation of marijuana can be effective at increasing turnout.

“You have to put something that gets people off their bums,” Prof Reilly said.

Commentators think a high number of Americans will be motivated to cast their vote on November 5 – perhaps even a record-breaker.

This is a stark turnaround in expectations from a few months ago, Prof Reilly said.

“It was shaping up to be a very low turnout election if Joe Biden stayed in the race,” he said.