‘Code name and a memory stick’: Secrets I knew about the MH17 bombing

Ten years ago Malaysian Airlines flight MH17 was shot down by a Russian missile. Charles Miranda got to the crash site before police. He had a coded identity, and had a secret memory stick.

World

Don't miss out on the headlines from World. Followed categories will be added to My News.

“Da da, yes it-sk here, it-sk here,” the heavily accented Aleksandr drawled unconvincingly as he crunched the gears of his ageing Zaporozhet car to get it up the steep dirt track outside Hrabove village.

On July 17, 2014, Malaysia Airlines flight MH17 had mysteriously plunged out of the sky and crashed in Ukraine’s east, killing all 298 passengers and crew including 38 Australian citizens and residents.

An image of a burning fuselage was almost immediately distributed by a world press agency but its location was referenced as just in east Ukraine.

I protested to Aleksandr and repeatedly stabbed the image on my phone with my finger that showed a burning fuselage on endless flat fields of sunflowers with not a mountain in sight.

“No, this is where I want to go, here flat flat, flowers, not up a bloody mountain.”

Aleksandr was a hole in the wall fruit and veg seller in Donetsk, in east Ukraine, but he spoke just enough English, Ukrainian and Russian, the latter critical as the border region had already been overrun by Russian troops and proxies including heavily armed Wagner mercenaries in a bloody early attempt to annex the eastern flank of Ukraine.

But for $US100 a day, Alek pulled the metal shutter on his tiny customer-less grocery shop and agreed to be my driver, translator and ultimately saviour.

As we rattled to the hill rise, I saw a farmer do the sign of the cross as he leant on his hoe and bowed his head before pockets of flame and black smoke in front of him which I took to be a crop burn off.

It was of sorts, albeit unintentional.

There in the middle of it all were the remains of a Boeing 777 cockpit, burning refuse and the distinct stench of death I knew only too well from having covered the 2004 Asian tsunami aftermath from a village in Thailand.

Little known at that time was the aircraft had come down in three major parts and the race was on – on the orders of the Kremlin – to secure and sanitise the sites and all the evidence.

Many talk of the Russian war on Ukraine as having entered its third year from February 2022, when tens of thousands of Russian troops and their tanks rattled across the border as, overhead, hundreds of missiles and drones pounded the capital Kyiv.

But the war that threatens to engulf the world today really began exactly a decade ago this week – July 17, 2014 – when Russia authorised and enabled the shooting down of a commercial passenger jet, then spent years trying to cover up the war crime.

EARLIER INVASION

Three months before MH17 was brought down, hundreds of Russian troops and mercenaries had already invaded Ukraine, linking up with Ukrainian separatists who had created a “capital” in Donetsk to lead a break away movement.

The push in April that year was led by a Russian commando Igor Girkin, who took control of government buildings in the city of Sloviansk, in Ukraine’s Donetsk district, and declared the region an independent “republic” which would swear allegiance to the Russian Federation.

His forces were dubbed “Little Green Men” as they were masked and dressed in nondescript uniforms. Like before its 2022 invasion, the Kremlin denied all knowledge of everything.

The region’s troubles flared from the climax of the popular “Euromaidan” bloody uprising in Kyiv in February 2014 that culminated with the Kremlin-backed puppet president Viktor Yanukovych forced to flee office after stalling on European support.

The instability prompted Russia, at the behest of Yanukovych, to invade or risk Ukraine joining the European Union.

Girkin was appointed “minister for defence” in the self-declared Donetsk People’s Republic before his rebels shot down MH17.

He and three others would be found guilty of mass murder and sentenced in absentia to life in jail with an international arrest warrant issued, and while he admitted “moral responsibility”, denied pushing the button on the missile system.

He would later publicly criticise Vladimir Putin and in January this year was sentenced to four years’ jail.

PRACTICALLY ALONE AMONG WRECKAGE

Aside from the lone farmer who on arrival would lose interest and wander off, there was no-one on the hilltop among the remnants of MH17 and those who had travelled on the doomed flight.

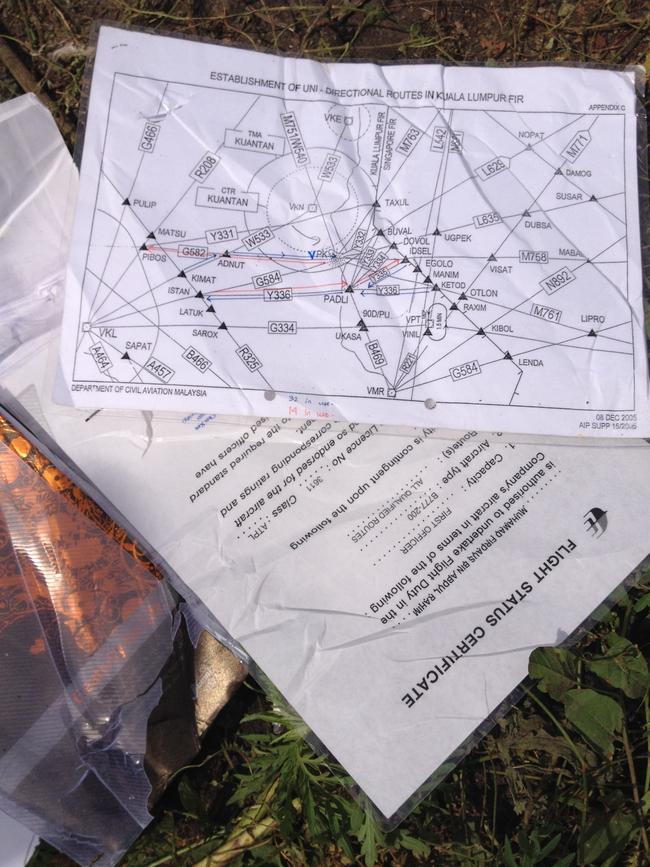

Despite the hour, I rang a contact in Canberra from the Australian Federal Police to seek advice on what to do. Aside from the remains and personal belongings in the cockpit was the flight log book, certifications, maps and charts, the co-captain’s flight bag with his mobile phone and passport, and other important evidence. Presumably somewhere beneath the pile was also one of the black box flight recorders; one had reportedly already been found by the separatists.

At that stage, none of the AFP or other authorities were in Ukraine’s east as it was a war zone and the mass entry of armed foreigners would be considered tantamount to entering conflict.

I rang the Netherlands, where some of the advance party of Australian investigators were setting up a base, and was told in no uncertain terms I was to enter a crime scene and I should touch nothing.

I protested as it was about to rain and the evidence, including a log book oddly marked in pencil, would be lost. We had also passed a convoy of militia vehicles on the move with many Little Green Men.

‘IT WAS ALMOST BIBLICAL’: WHAT ORPHANS WITNESSED

The MH17 aircraft – which ironically first flew exactly 17 years to the day of its shooting down – was on its usual flight path from Amsterdam to Kuala Lumpur over Ukraine’s east despite warnings two months earlier that rebels were suspected of being armed by Russia with surface-to-air missiles.

This was evident as several Ukrainian air force aircraft had been shot down in the weeks prior. The aircraft was cruising at 33,000 feet when contact was lost about 4.20pm local time.

Locals heard the bang but were accustomed to explosions in their embattled area.

On the outskirts of Donetsk, children from an orphanage were enjoying a garden lunch before one of the children pointed aloft and declared “big birds flying to us from the sky” before bodies and debris crashed all around.

“It was almost biblical,” a woman at the orphanage later recounted.

“They (children) hear shelling and bombings every day nearby and here they are in the garden when bodies and things fall. Can you imagine that?”

WITNESSED CRASH SITE CLEAN-UP

As a compromise, I agreed to not touch or collect any possible evidence from the hilltop site but instead use my iPhone to methodically take images of items and the scene.

I started doing this before out of nowhere a boy with a fluffy moustache, possibly around 16 years old and wearing combat gear, came up over the far side of the hill.

He was carrying an ancient looking bolt action rifle and started yelling instructions in Russia in ever increasing fear and frustration as he raised the weapon to his shoulder.

After a brief stand off, Alek jumped in front of him and violently pushed the weapon down as he began yelling at the boy in Russian about showing respect to elder patriots. It was a bluff but left the boy soldier close to tears before he ran away.

“Now we need leave, he come back with many friends,” Alek said with a cheeky grin.

Within 30 minutes, several vehicles had arrived with dozens of men in overalls and, using metal-cutting chainsaws, large chains and winches, began hauling and chopping the aircraft up. We watched from afar as the site was sanitised, hauled into trucks and flat top trucks and evidence gone.

A year later I would spend two days providing testimony to the Dutch-led investigators putting together a brief for The Hague’s war crime tribunal.

Such was the sensitivity, and perhaps a little over dramatic, I was escorted off an aircraft by armed police at Schiphol in Amsterdam, and would later be given an identity code in lieu of a name so my direct two days of evidence would not be publicly attributable, apparently for my own safety.

“There have already been threats,” a Dutch officer said, declining to reveal by whom or to whom, but adding “that’s the way Russia works”.

The site prior to clean-up was important but so too was a memory stick I would spend a year trying to secure.

I first saw it in the Ramada Hotel in Donetsk, a hotel that was one of the few still serving alcohol and thus became a gathering point for Russian soldiers and militia, prostitutes and a few European-based journalists still willing to put up with daily shelling.

A Russian-backed militia soldier was playing a video on his laptop from the stick for a dozen drunken colleagues and their female friends, showing raw handycam footage shot almost immediately after the plane was brought down. The militia on the 17-minute film were ordered to span out across the fields and find the bodies “and parachutes” of what they thought was a Ukrainian troop-carrying transporter plane.

There was much discussion on the film about the shooting down, then bewilderment, a remark about “Chinese (bodies) everywhere” (more likely Malaysian), then realisation – “it’s a passenger plane” before a commander orders filming stopped.

Reaction from those watching in the Ramada, as much as those filming it, was one of genuine surprise. They shook their heads, winced and realised they had effectively brought the Western world into their war.

Suddenly all the triumphant discussion in Donetsk of the past few days about it being a Ukrainian Antonov transport aircraft carrying Ukrainian troops and the great victory of it being shot down was shut down. The media was also no longer welcome in the self-declared republic.

The full raw footage, passed among rebels and others for sale, would months later be secured and a year later prove “invaluable” according to investigators.

RUSSIAN FORCES CULPABLE

Last month, Ukraine inched closer to joining the EU with formal talks in Kyiv, albeit largely ceremonial, to push through the reforms required to gain membership.

Before Russia even invaded Ukraine in 2022, already more than 15,000 Ukrainians had been killed from 2014, including those from MH17.

The figure is now 10 times that.

The war continues to be waged by Russia but it should never be forgotten it was that country’s military – specifically the Russian Ground Forces 53rd Anti-Aircraft Missile Brigade – that supplied the Buk missile firing system that brought down the flight in its misguided quest to annex Ukraine and should forever be held legally and morally culpable.