Bashar al-Assad’s demise is unlikely to lead to peace

A dictator is gone. But Russia, Iran and Islamic State extremists are all circling as the fallout from 50 years of repression shapes the Middle East.

World

Don't miss out on the headlines from World. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Democratic utopia? Religious-extremist dystopia? Anarchic gangland rule? The world is watching tensely as Syria struggles to emerge from 50 years of Assad dynasty repression.

The ex-prime minister of Syria’s fallen regime was led out of his offices under armed arrest.

“I won’t leave, and I don’t intend to leave,” Mohammad Ghazi al Jalali said in a video statement.

“I expect in a peaceful manner to guarantee the continuity of the public authorities, institutions and the safety and security for all citizens.”

His sudden, uncharacteristic concern for the public good was mirrored by his captives.

The terrorist organisation Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), a derivative of al-Qaeda, promised an uncommonly tolerant transition of power.

“Tomorrow morning when institutions start to conduct their business of services, security and policemen, I hope from everyone who carries a weapon to go to his base and to commit to his division, battalion or brigade,” added HTS commander Abu Mohammed al-Golani (whose real name is Ahmed al-Sharaa). “We will not accept or allow the chaos of arms or firing on the streets at all.”

Al-Golani said his hardline Islamist group was working to form a new government.

The success or failure of this transition will pave the way for the entire Middle East.

As will any new government’s characteristics.

Syria, after all, is a vast and geographically complex land with many diverse cultural groups.

“We should not expect a democratic secular rule,” says Charles Sturt University Islamic Studies director Mehmet Ozalp.

“The new government is also unlikely to resemble the ultra-conservative theocratic rule of the Taliban.”

But Syria’s rebel factions are not the only forces attempting to shape the battered nation’s future.

Russia still wants its Middle Eastern bases. Iran still wants a military and cultural “buffer zone” between itself and Israel. And, beneath the surface, Islamic State extremists are still striving to create their kingdom of heaven.

“For too long, Syria has been neglected by the United States and its Western allies, which deemed the Assad regime unmovable, until they discovered it wasn’t,” argues Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) analyst Natasha Hall and International Crisis Group (CG) director Joost Hiltermann.

What is to come?

“Levantine history teaches us to be deeply concerned when dealing with such a fractious society in trauma after a decade of internecine war, torn in different directions by various foreign and non-state actors,” warns London-based geostrategist Alexander Patterson.

What unfolds over the next few days will likely set the scene for what will come.

“Syria’s future, and the region’s, is filled with uncertainty,” adds International Crisis Group director Joost Hiltermann.

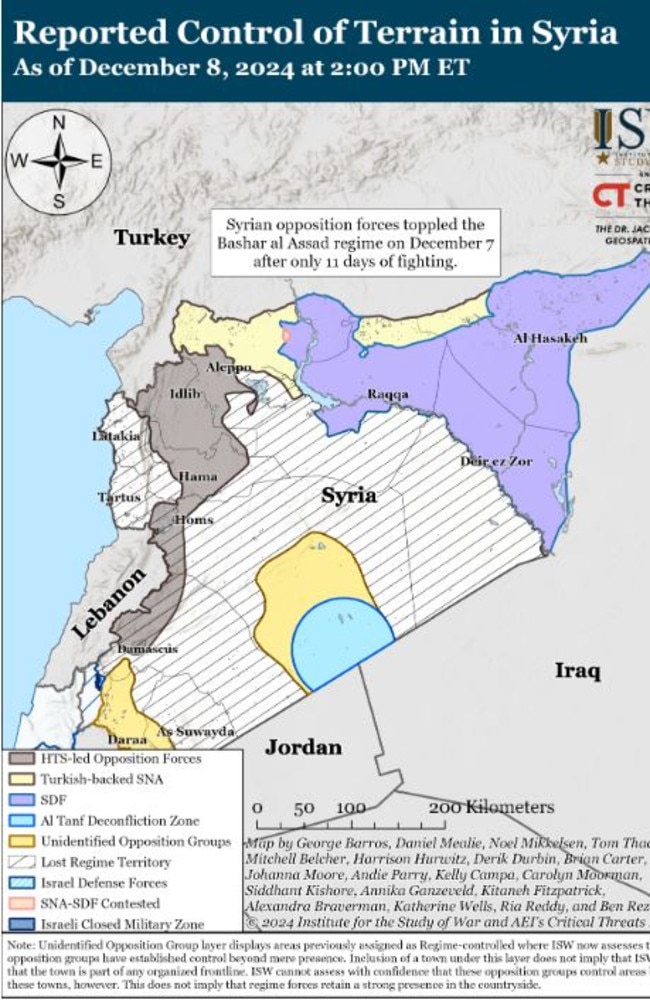

“Clashes are already ongoing between the Turkish-backed Syrian National Army (SNA) armed groups in the north and the Kurdish-dominated SDF (Syria Defence Force).”

Now is the time for payback.

Jubilant rebel forces must reward their backers. And the hunt is on for members of Assad’s secret police and privileged elites.

But it’s also a time to establish a new pecking order.

“The new leadership will now try to ensure there are no armed groups capable of contesting their rule, particularly remnants of the old Assad regime and smaller factions that were not part of the opposition forces,” predicts Ozalp.

But will this be done in a manner that establishes the rule of law?

Or as a continuation of the millennia-old culture wars?

“Military collapses and local dealmaking would suggest that efforts to adapt existing structures may be the initial approach,” says Patterson. “The rebels would be well advised to be inclusive; an Iraq 2003-style purge of the Baath party would result in the same sort of broad insurgency that sparked – and mass executions would be even worse. This will be a key question to watch. “

And Syria’s victorious rebels represent an unlikely alliance.

They are a diverse assembly of cultural groups, sects and political movements.

“HTS will have to share power with other Syrians,” Patterson adds. “We may be unsurprised to witness a descent into chaotic power struggles between factions, or – if homework has been done – we may be surprised by a less radical government than HTS’s terrorist pedigree would suggest.”

Terrorists, or freedom fighters?

“Syrians are celebrating the fall of a dictator who put them through a protracted civil war and the end of his family’s half-century iron grip on the country,” international relations analyst James Horncastle writes in The Conversation.

“But the opposition forces that brought him down in 2024 aren’t the ones supported by the United States and its allies in 2013. Fundamentalist groups, versus the Americans’ preferred moderate organisations, now dominate the opposition.”

Western nations rallied to support the “Arab Spring” uprising of Syria’s populace in 2011.

But the battle against Islamic State quickly shifted their attention elsewhere.

“Syrian opposition forces have undergone a stark evolution following years of struggle,” explains Horncastle.

“The loss of western allies and the enduring nature of the Syrian civil war itself gave rise to increasingly radicalised voices. Most prominent among them is Hayat Tahrir al-Sham.”

The Sunni-Islamic HTS is designated a terrorist group by its primary backer - Turkey.

But Turkey is less lenient towards ethnic Kurds seeking to establish a new homeland in Syria’s northeast.

It has designated this US-backed community a terrorist organisation. And it has launched regular cross-border attacks on the group’s strongholds.

“Meanwhile, thousands of Islamic State fighters remain in prisons in the northeast under SDF control,” warn Hall and Hiltermann. “Those fighters, should they escape or if cells should reemerge, would be a major spoiler for any post-Assad government and for the region.”

Adding fuel to the fire is Israel’s invasion of the demilitarised zone on its border with Syria. It and the US have been conducting large-scale airstrikes against suspected chemical weapons depots, ammunition dumps and Islamic State encampments.

In the meantime, Al-Golani appears set to be anointed the founding president of a new Syrian regime. But his success will depend on how power is distributed.

“It seems the opposition was not prepared to take over the country so quickly, and they may not have a power-sharing agreement,” Ozalp says. “This will need to be negotiated and worked out quickly.”

Fragile unity

“It’s important to note that these disparate forces were never entirely united,” says Horncastle. “Instead, the Syrian opposition ranged from liberal and moderate elements to Islamic fundamentalist forces. The only thing that truly united them was opposition to al-Assad’s tyranny.”

That unifying force has now fled to Moscow.

And the power vacuum the dictator left behind is pulling in many different directions.

“A radical Islamic fundamentalist government must remain the core assumption if HTS seizes power over the heads of others,” Patterson warns in his essay for the Royal United Services Institute.

“This would not bode well for a country crippled by sanctions and reliant on Iranian fuel and foreign humanitarian aid.”

So far, HTS chief al-Golani is making all the right noises.

In an interview with CNN, he asserted that his circle of followers had evolved their interpretation of Islamic dogma. He sought to reassure listeners that he would protect the freedom and rights of different religious and ethnic groups.

“The question of whether this tone will remain and whether other insurgent groups and opposition factions will follow his lead is another question,” argues Hall and Hiltermann. “As more Syrians return to the country, including various opposition leaders, there will be inevitable tensions.”

And the reality on the ground is not pleasant.

Syria’s economy has been all but destroyed.

Some 14 years of civil war have slashed activity by 85 per cent. Infrastructure has been destroyed. Crops and orchards are left untended. Hyperinflation is running rampant.

Now, the 4.82 million people who fled the tyranny and devastation (about one-fifth of the total population) are looking to return home.

“Many people may find their homes looted or new families living in them. Armed groups within Syria and the exiled opposition may struggle for power,” the CSIS and CG analysts note.

“Preventing further tragedy will require Western countries and Gulf Arab states, in particular, to reach out to the new leaders in Damascus and steer them toward pragmatic, if not democratic, governance. Having at last regained hope from the fall of the House of Assad, the Syrian people expect no less from the countries that have for so many years allowed the country’s agony to continue at their expense.”

Jamie Seidel is a freelance writer | @jamieseidel.bsky.social

Originally published as Bashar al-Assad’s demise is unlikely to lead to peace