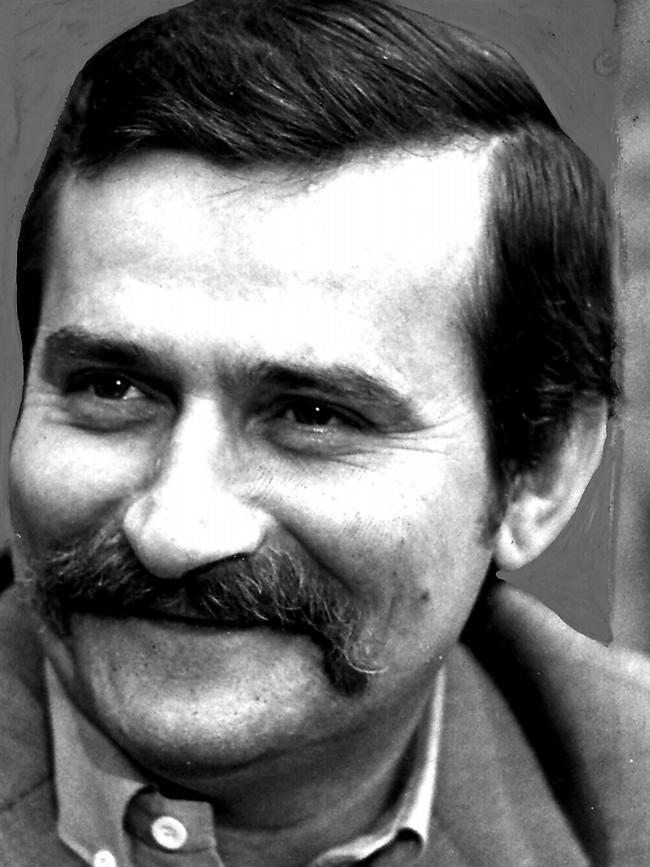

Work reformist Lech Walesa went on to become president of Poland

WHEN a stocky electrician took charge of a strike at his former workplace in August 1980, it became the national Solidarity union movement and would eventually force the puppet Soviet-run Polish government to hold free elections.

Today in History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Today in History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- MIDAIR COLLISION SENT PLANES HURTLING INTO SUBURB

- FAME ELUDED CHILD STAR AFTER SUCCESS OF OLIVER!

- BLAST SURVIVOR PROVIDED CLUES ON BRAIN FUNCTION

THE stocky electrician had been fired from the Lenin Shipyard in Gdansk four years earlier, but when he climbed the wall of his former workplace in August 1980 he was not trying to get his job back. He wanted to join his former work colleagues who were striking over the sacking of crane driver Anna Walentynowicz.

Walentynowicz was sacked for complaining about wages and working conditions, and for agitating for a memorial to workers who had been shot dead by communist militia while protesting in the 1970s.

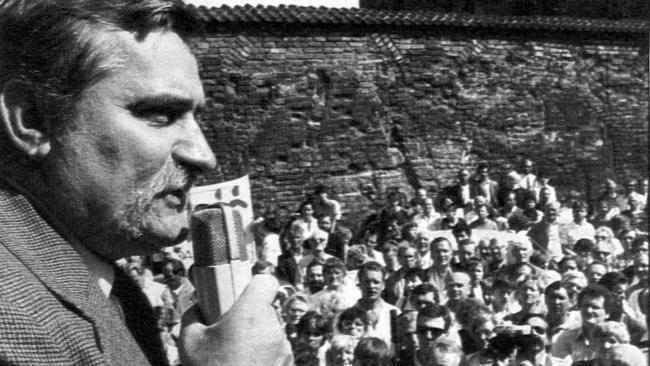

After making it over the wall the electrician jumped up on a crate and said: “Ladies and gentlemen, you know me, Lech Walesa. I was fired from here for making the same protests as Anna. This time we will make sure she keeps her job.” It was a pivotal moment in modern European history.

Walesa, born 75 years ago today, took charge of the strike and it became the national Solidarity union movement, which eventually forced the puppet Soviet-run Polish government to hold free elections in 1989. This, in turn, encouraged other communist nations to rise up against their Soviet overlords. Walesa, therefore, played an important role in the eventual collapse of Soviet power in Eastern Europe.

Born on September 29, 1943, in Popowo, Poland, Walesa was the son of carpenter Bolesaw Walesa and his wife Feliksa. Before Lech was born, German-occupying forces sent his father to a forced labour camp. He returned at the end of the war, but his health had deteriorated and he died soon after.

Walesa barely knew his father but was close to his mother, who taught him to be pious, tenacious and stand up for what he believed in. His mother married Boleslaw’s brother Stanislaw in 1952.

Walesa went to a vocational school and graduated in 1961 as an electrician but got work as a mechanic at a machine centre. He worked there until 1965, then served two years in the army, attaining the rank of corporal before his release in 1967, after which he got a job at the Lenin Shipyard, a government-run facility that built ships for the navy.

The late ’60s was an era of growing unrest about government control over the people and the lack of freedom, particularly to protest. Walesa became involved in struggles against the government, in 1968 he showed solidarity with striking students by urging workmates not to take part in government-organised rallies condemning strikes.

But he also found time for romance. In 1969 he married flower seller Danuta Golos, who worked in a florist near the shipyard.

Walesa also organised shipyard workers to protest against food shortages and price rises in 1970. The protests resulted in the deaths of 30 demonstrators at the hands of police. He was briefly detained by police, but escaped imprisonment. Marked as a troublemaker he would be arrested several times over the next few years for taking part in dissident activities.

When mass anti-government protests again broke out in 1976, Walesa was again in the thick of the action as an anti-government shop steward. He lost his job. He worked on a series of temporary jobs, but also with an underground organisation Free Trade Unions of the Coast.

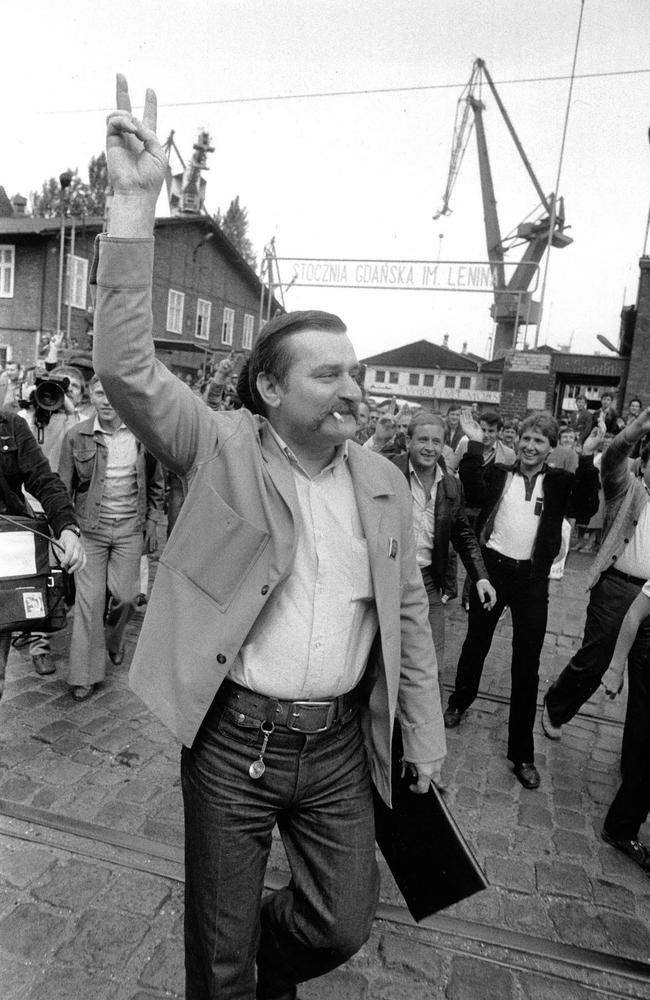

In 1980 when workers at his old shipyard went on strike he jumped the wall to join them. He urged the workers to stay in the shipyard so they couldn’t be arrested or shot during a street protest. He was elected head of the strike committee and, as tanks and troops surrounded the compound, Walesa negotiated with management for a peaceful settlement.

The rising tide of protests in Poland prevented the government from using force to settle the strike, because violence may have sparked an uprising. The government gave in to demands, but Walesa was asked by other striking workplaces to continue the strike out of solidarity. He agreed and became the leader of a nationwide general strike, one of the demands was to be allowed to form free trade unions.

On August 31, 1980, Walesa met with Polish deputy leader Mieczyslaw Jagielski and signed an agreement that guaranteed the right of workers to strike and organise their own unions without state interference. People flocked to join and they formed a federation that became Solidarity (Solidarnosc).

In 1981 martial law was declared by Polish leader General Wojciech Jaruzelski and Solidarity was outlawed and Walesa detained. After his release he went underground to continue resistance to the government. In 1983 he was awarded a Nobel Peace prize, but he sent his wife to Oslo to collect it fearing he wouldn’t be allowed back into Poland.

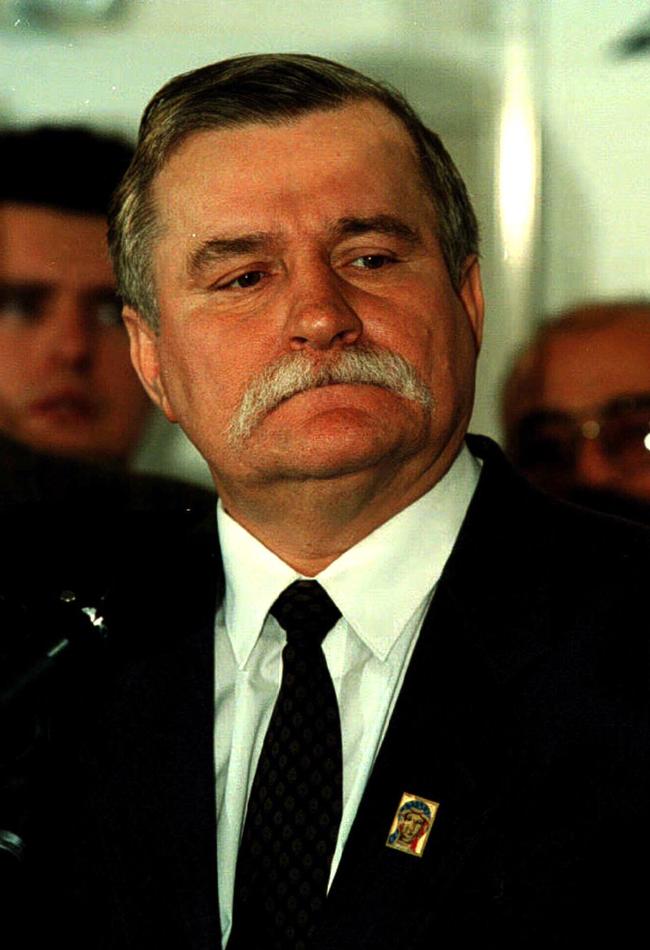

Poland’s economy began to falter in the late ’80s and Walesa and Solidarity were there applying pressure to the government. In 1989 free elections were held, the communists were ousted in favour of members of Solidarity. Walesa declined to serve as premier, but was elected president at presidential elections in 1990.

Walesa saw the country’s transition to a free market system. However, by 1995 his popularity had begun to slide due to dissatisfaction with his leadership. He was voted out and at the 2000 election only polled 1 per cent of the vote, causing him to quit politics and, in 2006, quit Solidarity.

He set up a foundation to educate people about Solidarity and to promote democracy worldwide.