Vietnam dictator Ngo Dinh Diem was first foreign leader to visit Canberra

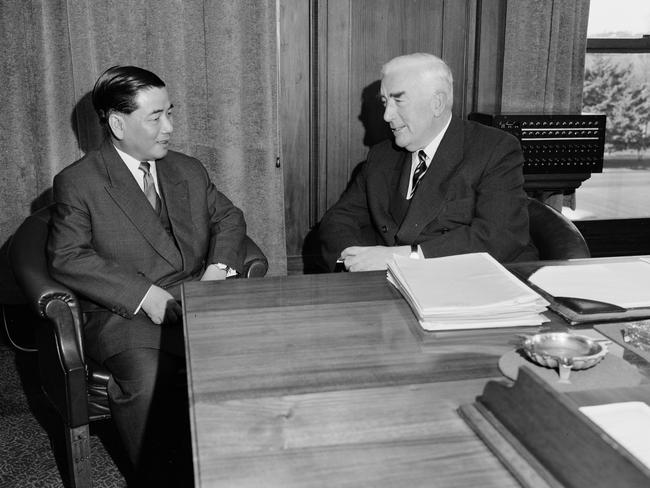

It was a coming-of-age celebration when the first foreign leader to visit Canberra touched down 60 years ago, even if official guest Ngo Dinh Diem could be considered an illegitimate president of an illegitimate state.

Today in History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Today in History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

IT was a coming-of-age celebration when the first foreign leader to visit Canberra touched down 60 years ago, even if guest Ngo Dinh Diem could be considered an illegitimate president of an illegitimate state.

Diem had ruled South Vietnam for two years after winning a referendum with 98.2 per cent of the vote, including 605,000 votes in Saigon where the electoral roll had 450,000 names.

He arrived in Australia for four days on September 2, 1957, at the invitation of Liberal Senate president Alister McMullin and parliamentary speaker John McLeay. The invitation followed an Australian trade delegation to South East Asia, led by Senator John Grey Gorton, in December 1956. At a lunch for Diem, Prime Minister Robert Menzies praised the “astonishing part” he had played in Vietnam’s struggle for independence and its resistance to Communist aggression.

Life magazine enthused that “Diem has roused his country and routed the Reds” as he arrived in the US in May 1957, continuing, “Diem is respected in Vietnam for the miracles he has wrought. Order has replaced chaos. Communism is being defeated.” The US was then contributing $400 million a year to pay 75 per cent of South Vietnam’s public costs, including supporting a 150,000-man army.

Australian reports were less flattering: “When austere, scholarly little Diem took over as his country’s Premier three years ago, the wise money was stacked against his political survival,” one newspaper observed. “It seemed a safe bet. Diem, who once intended becoming a Roman Catholic priest and has continued a life pledged to chastity ... faced a formidable phalanx of troubles.”

Among Diem’s troubles was that having liberated themselves from France in May 1954, most Vietnamese favoured Communist leader Ho Chi Minh. Emperor Bao Dai, reappointed by France in 1949, had appointed Diem as prime minister in July 1954.

Born in 1901 to a noble family who, in the 17th century, were among Vietnam’s first Roman Catholic converts, Diem served in Bao Dai’s ministry in 1933, but resigned in protest at French control. In 1945 he was captured and pressured to join Viet Minh forces to secure Catholic support. Diem refused and went into exile abroad for almost a decade.

At the mid-1954 Geneva Accords signing, France agreed to withdraw its forces and stipulated Vietnam was to be temporarily divided at the 17th parallel. The north became the Democratic Republic under Viet Minh leader Ho Chi Minh. The south was the State of Vietnam, under Bao Dai, to limit Ho Chi Minh.

At Geneva all parties agreed to a democratic national election in 1956. With the north more populous, Ho Chi Minh was confident of victory. After investing $2 billion in French Indochina to stop “domino effect” Communism in Asia, the US supported Diem as anti-French and anti-Communist.

In Saigon, Diem found a bankrupt treasury, organised crime rackets and a refugee crisis as one million farmers and Catholics left the north. Ho Chi Minh also urged southerners to wage a guerilla war. In July 1955, Diem announced he would not join reunification elections.

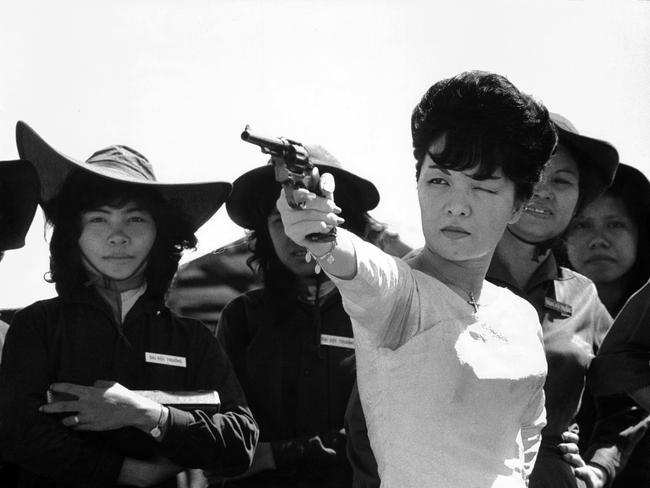

Diem’s support came from US advisers and his brothers Nhu, Thuc, Can and Luyen. Nhu and his wife Tran Le Xuan, later known in the West as Madame Nhu, moved into the presidential mansion. As Diem’s de facto First Lady, Madame Nhu had befriended Americans known to be CIA agents at the Saigon embassy, to win support for Diem. Nhu, reputedly an opium-addict and trader, oversaw the creation of a special forces unit in the Republic Army, and ran private armies and anti-communist “death squads” to secure Diem’s resounding victory to oust Dai in a referendum in October 1955. The Ngos then turned totalitarian control against all opponents, while their favouritism to Roman Catholics alienated the majority Buddhist population. Nhu’s private army also spied on officials and army officers.

In 1956 elections, again reportedly rigged by the Ngos, Madame Nhu won a National Assembly. Her father became US ambassador, while her mother was made a United Nations observer. Madame pushed through laws to ban concubines and outlaw divorce, when her sister was reputedly having an affair and desperate for her own divorce. Morality laws also banned contraception, dancing, beauty contests and underwire bras.

In April 1956 an Australian reporter observed that “South Vietnam is stiff with police, checking, controlling, supervising, guarding, and frequently shooting. The police of South Vietnam, in all their variety, are forever seeking and trailing after Communists.”

Diem’s rule ended horrifically in 1963, when his forces killed several people at a May rally to celebrate Buddha’s birthday. Buddhists staged large protest rallies, where three monks and a nun self-immolated. Madame Nhu’s public response cost US support: “I would clap hands at seeing another monk barbecue show. Let them burn. And we shall clap our hands,” she said.

She was in Beverly Hills when a bloody coup, later revealed to have US government support, ended the Diem regime on November 1, 1963. Learning Diem and Nhu had been killed, Madame Nhu noted, “Whoever has the Americans as allies does not need enemies.”