Ironman Trevor Hendy turned to a kinesiologist to find ultimate success

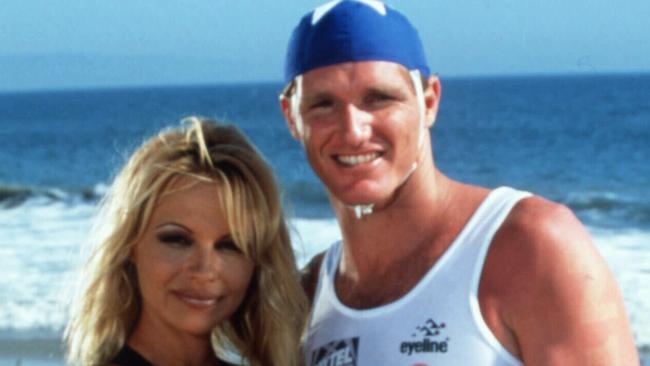

Legendary Ironman Trevor Hendy had a cabinet full of trophies and was at peak fitness when he felt most ‘lost’. It took a kinesiologist to help him find real success.

News

Don't miss out on the headlines from News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

I grew up watching the Uncle Toby Ironman Series as a young boy. Darrell Eastlake was the voice of the sport, and Trevor Hendy was the face of it. I would tune in whenever it was on, and barrack for him. There was something about Trevor Hendy I was drawn to. Years later, I was introduced to him by a mutual friend. After meeting him, I was very glad I’d been cheering for him all those years ago. We spoke about a journey that led to great success, but not happiness ... until it did.

HM: Trev, how safe is it to learn to swim in the Daly River in the NT?

TH: It’s not safe, Hame, but with all the crocs about, it guarantees you become a good swimmer! It’s funny because we’ve just come back from Cape York, and I spent three-and-a-half weeks up there. I felt like I was at home. People know me to be at home in the water, and I’ve always felt at home in the water. It wasn’t until I got up there that I remembered that a lot of my childhood was spent in the wilderness, in the bush, particularly in the Northern Territory and right throughout Northern Queensland.

HM: Your old man, Ron, gathered the family up in 1971, and put a caravan behind the blue Dodge truck, and took the family around Australia. It seemed life-changing for you, and the family.

TH: It was, absolutely. My father had the courage to get off the grid and leave the normal picket-fence existence behind to see what was out there. He sensed that there was something else to discover. He said although everyone else couldn’t wait to travel overseas and see the world, he couldn’t wait to see his own country.

HM: It has left a lasting impact on you?

TH: A profound one. I think those years are why I feel so connected with my country and the people in it. My indigenous connection from travelling around Australia, stopping and playing with all the original kids of the country, has stayed with me. When I see them now as adults, they walk up to me and say, “you’re one of us”.

HM: Your dad was always teaching you on that trip.

TH: Always. He’d pull over in the middle of nowhere, and he’d take my sister and I for a walk off into the wilderness. Mum would be cooking up some rabbit or chicken or fish, and Dad would walk us around in circles and do all sorts of different things for an hour or so. Then he’d say, “OK – take us home”. That taught me to always know my way home, and I’ve needed that ability a lot in my life. Whenever I’ve lost my way in life, I’ve always been able to find my way back. He taught me that when you leave home, or you go off the beaten path, or you lose your way, make sure, however long it takes, you know how to get back. It also taught me that home was where the heart was, where the family was, not where you owned a property. I could be at home anywhere after that.

HM: You settled on the coast and ended up being enrolled in the Surfers Paradise Primary School. You were a sporting standout. Was it your mate Stewart who got you involved in nippers?

TH: It was! I was riding home from primary school, and Stu was walking around the corner, with dad behind me. As he was walking towards me, he said, “Trev, you want to come to Nippers on Sunday?” I was ready to decline him, but dad stepped up next to me, put his hand on my shoulder and said, “He’d love to”.

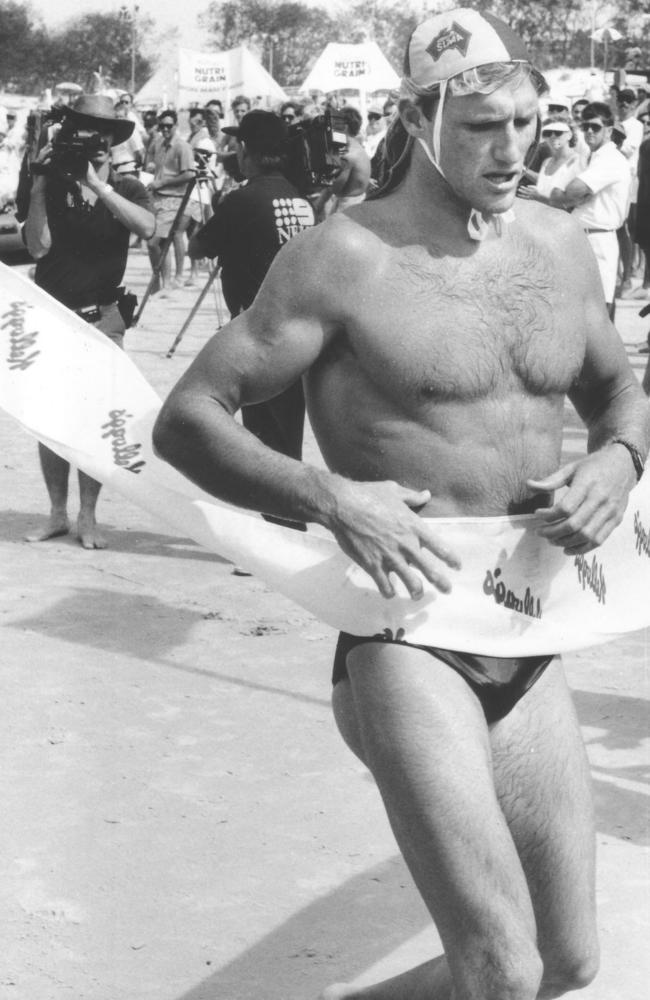

HM: That’s where it started – from you about to decline, to your dad saying “yes”, and six Australian championships later …

TH: If dad wasn’t there, I wouldn’t have ever competed. Talk about sliding doors. I went off for my first session of Nippers. It was the first time I had to swim across the pool, six laps … it felt like more and I cried, mostly because I was scared of the competition, I was used to swimming in rivers not competitions. I did the beach flags and managed to get a flag a few times, and I saw my mum cheering, and I was hooked on it. I knew there was something in it for me. And I really connected with the water. I ended up riding waves for hours while others were training. When they were all burnt out and gave up as teenagers I hadn’t even really trained yet, I was only just getting started. That love of the ocean was what set me apart from the others when the battles were really on. It was my biggest passion in life.

HM: There’s a great story from when you weren’t even the best lifesaver at your club, let alone the world, and you were asked to write a few things down.

TH: Bill Haylock. Bill said, “Write down your biggest goal, not the one that you think you can achieve, but the one you truly want to achieve.” I wrote down: Australian Ironman Champion.

HM: Where were you ranked at this point?

TH: Fifth of 6th in my own surf club as a junior, out of 300 clubs in Australia! I had no right to write down Australian Ironman champion based off my results. When I sat with him, he looked at it and said, “You want to be Australian Ironman champion?” I said, “Yep.” He then said, “Are you willing to do what it takes?” He said, “It’s great to have a goal and a passion, but it’s all about willingness. Are you willing to do what it takes?” The answer was “yes”. It was yes because every part of me was connected to that goal at that stage of my life, and it was a spiritual goal as much as a physical and personal goal, because it was something I was craving and desiring, to fulfil what I was capable of. He supported that, got behind me, and it allowed that to blossom and bloom.

HM: And?

TH: Within two years, I was Australian Open Ironman champion! The second youngest to do it, behind Grant Kenny. When I won my first Australian Open Ironman title, I rang Bill immediately afterwards as it wasn’t televised at that stage. He picked up the phone, and before I could say anything, he said, “How much did you win by?” I said to him, “How did you know?” He said, “I knew that day that you sat down in front of me it wasn’t a matter of if, just a matter of when. Three weeks ago, I knew the when was now, and I knew you were ready.”

HM: Your success was phenomenal, the trophy cabinet was full, and you would assume, given how you had grown up, that it was what was going to give you a great sense of happiness. But it didn’t.

TH: When I go back to that period of time, I was so lost. I had won just about everything, but I wasn’t happy. The world intimates that success equates directly to happiness, but that just isn’t true. You and I watched a good friend of ours finish his coaching career at Collingwood on Monday with a fairytale win. When asked the question about the ultimate success eluding him, he said, “What is the ultimate success?” I feel we are really lost around what success is. Success shouldn’t be determined by winning and gathering and gaining things. This is what I ultimately realised and it was a huge relief to realise that my wellbeing, my inner-happiness shouldn’t be and isn’t connected to results. Results are great but there is so much more to life than that and results can sometimes even cover up all of that other wonderful stuff and particularly the challenging stuff that can be avoided when you think you are winning and that is all to it.

HM: Who was the one that helped you realise that the winning wasn’t going to feed your soul, and that you might have to look elsewhere to find the inner happiness you were searching for?

TH: There were a whole series of people and moments that helped me become truly happy. I’d spent my life trying to win everything, but then suddenly it was as if my spirit was saying “No, it’s not about winning everything, it’s about winning on all levels”. My body had started to clap-out as if to say “I’m not going to take you further down this path unless you make some changes”. My amazing manager at the time, Geoffrey Schuhkraft, sent me off to Dr Keith Maitland, a chiropractor and kinesiologist, and he was outside the Ironman scene altogether! He was critical in changing so much in my life.

HM: In what sense?

TH: He told me that I wouldn’t win another world title unless I answered all these other questions that I had never addressed.

HM: Like?

TH: Mostly, emotional questions, about who I really was, what I wanted, and what was actually important to me. When he told me that, I smiled, as I did with everybody, but I wanted to punch him in the face. I thought he was wrong or at least my ego did and had a huge desire to prove him wrong, but luckily I didn’t. He was right. I had to work out who I was, and get a balance to be able to move forward. He’s still a great mate that’s been on the journey with me for so long and he led me to another friend and guide, Colin Brown. He passed away in the mid ’90s, but did a series of personal developmental work with me. He got me sitting in front of people who could see through my bullshit. When they’d say, “How are you going?” I’d say, “Yeah, good”, and they’d say, “No you’re not, you’re not good at all!” And they were right. Deep down it was refreshing to know that the illusion was over, the gig was up.

HM: People hadn’t really made you answer the question honestly?

TH: I found a series of people that sat in front of me, and instead of telling me how wonderful I was they would say, “You’ve got a lot of issues to work through. You’re hiding, you’re lying, you’re deceiving, you’re not being true to yourself, you’re not being true to others”. This was said to me with a very gentle but certain love, they were willing to tell me the truth and I knew I had to listen.

HM: Did you, deep down, know they were right?

TH: My first marriage had broken up, so that was a big slap in my face, and I realised I was more responsible for it than I’d like to admit. Jo, my second wife, and I started the journey together. We were both ready for a deep journey; the time was right and she stood by my side while we pulled our lives apart and looked deep into it, trying to explore what was real and what wasn’t. It was really powerful to look back on it and see that.

HM: You had a powerful moment when your son, TJ, was born.

TH: I had (daughter) Kristell, and TJ, with my first wife, Jacki. When TJ was born, and I held him in my arms, and his big brown eyes looked back at me, I had a really strong sense that I wasn’t the man I was meant to be. And that I was way off track. And as a result, I wasn’t proud to hold him! He was beautiful, but I wasn’t the guy that he needed to lead him, and that was unbelievably powerful and disconcerting. I had to work out who I was.

HM: Your wife, Jo, who’s with you now, helped you realise who you were, and allowed you to separate the person from the performance, and just allowed you to be you.

TH: Jo’s crying as you ask that question Hame, and I get really emotional too. I acknowledged Jo at my testimonial dinner in 2000, and as I acknowledged her and told those what she had done for me, and I felt this tidal wave of love and truth go through the room. Women were coming up to me afterwards saying, “That was the most beautiful thing” and

then punching their husbands and saying “Why can’t you speak about me like that!”

HM: Your testimonial was responsible for 37 divorces that night!

TH: And hopefully 37 guys sorting their shit out and addressing their own issues! Jo came into my life, and she reminded me of everything that I was deep down, not everything that I wanted to be, or everything that I thought I needed to be, but everything I truly was! Everything else dropped away to be honest. Every single day, I look at her and I tell her I love her. And the more I’ve been able to love Jo and let the love in, the more I’ve been able to love everybody and vice versa. It’s taught me so much about everything else, and it’s the key relationship to my life.

HM: Post-retirement, you decided that you would share what you’ve learnt, and try and help those that were in a similar spot to how you were. Many of us have, for a long time, been terrified of sharing who we are, and what we want, for fear of being persecuted for having the wrong desires, aims and goals. Everyone’s been fearful of sharing their vulnerability.

TH: Absolutely, me included. Go back to when we were boys, we kissed our dads, we hugged them, and we went on with our lives. We weren’t born with invulnerability. We were born open hearted, we were born loving every race, colour, creed and gender. We just loved life. It’s totally OK to struggle with vulnerability, because it’s not even really us that are struggling with it, it’s the conditioning inside of us, it’s our fear. It’s the way we’ve grown up. We’ve learnt this, but it’s not truly us.

HM: I read a few of your pieces on your website. One was “Significance - the silent thief of joy”. We are too worried about material possessions, too worried about things we don’t have or may not have. Is there something you see all too often that’s easy to eradicate that you teach a lot?

TH: Great question. What really comes to mind is the value we put on things. If we say, “I have to have that house, that car, that relationship, that raise, that acknowledgment, those letters after my name”, whatever it is, anything that is external to ourselves, we immediately put ourselves in a very precarious, fragile situation. We are either going to be happy or not based on whether we get those things, or not. It’s pretty cool to explore – chase and pursue things, and work on that creative part of you that can manifest it, but at some point, you have to realise that chasing everything outside of yourself is where the misery comes from.

HM: Misery comes from the constant, exhausting search for more, which has no end …

TH: Yeah, it comes from thinking “I’ll be happy when”. I’ll be happy when that person gives me respect. I’ll be happy when you do this for me. I’ll be happy when my hard work pays off. I’ll be happy when I get to that place. So delete whatever comes after “I’ll be happy when”, and just don’t need it. You can still chase it but don’t hang your happiness on it. What happens is you realise that it’s the opposite way around. I’ll get that when I’m happy! It’s a strange, curious thing that happens in the world, it eludes you, until you stop chasing it. That’s the key thing I see in people. The key thing I notice in people that are ready to change is that they’ve been brave enough to chase a lot of different things, and they’ve hit so many brick walls until they realise something’s got to give. Eckhart Tolle wrote The Power of Now, and he called it the inner readiness. When you have that you are on your way, you have had enough of all of these illusions that we chase. It sets you up to find true happiness.

HM: A simple attitudinal change can change everything.

TH: Absolutely. We’re all making excuses, telling stories and dramatising, dragging people into our side of the story. We’re these crazy, talented, potential-filled beings, but we’ve just got in this habit of saying things like, “I’ve got to take the kids to school”. It’s so simple just to change a word. “I get to take the kids to school.” One’s a complete blessing, a joy, an honour, and leads to you going through the rest of your day thinking you’re blessed. The other one is moping around going, “I’ve got to do this, I’ve got to do that”. We need to make the conditions inside of ourselves conducive to the good stuff. In Nelson Mandela’s inauguration speech, “Our deepest fear is not that we are inadequate. Our deepest fear is that we are powerful beyond measure”. It’s our light, not our darkness, that frightens us most. When you know that, you’re on the right track, that fear comes up. For every individual, that’s a very confronting and vulnerable thing, to step into who you really are. Which really means stepping out of your thoughts about yourself and life and steeping into who you really are, the you that isn’t thinking, that is just being. From there you can create anything.

HM: You’ve had so many different chapters in your life. The chapter that you’re going through now with the Boot Camp For the Soul, and the self-coaching, are you through transforming others’ souls, minds and bodies, putting your soul, mind and body in the best shape it’s ever been?

TH: Without doubt, and also constantly bringing up the next layer of shit that I haven’t looked at in myself!

HM: As you help others, you are continually helping yourself?

TH: Absolutely. Where I am now, I am having so many realisations day to day. That’s what makes my relationship with Jo amazing. We don’t look to each other for fulfilment, we actually bounce off each other constantly. We are self-fulfilling, and then reflecting with each other and sharing it. Jo has The Sacred Sister Project. She works with teenage girls, their mums and their teachers. She works in schools, at seminars, one on one. She is constantly challenging herself to sit in front of people as the best version of herself, to give them the best chance to find the best version of themselves.

HM: It’s a nice spot you’re both in. I assume of all of your extraordinary success in the water, and in competition, nothing beats 2015. An old, retired, overweight, middleaged man comes out and achieves something great with a young man that just happens to be his son.

TH: Yes! The same kid that made me realise I wasn’t the man I needed to be, came to me at 20 years of age, 20 years later, and said, “Do you want to do the Board Rescue together?” That’s the prime lifesaving event at the national titles! It’s the event we do most, the thing we do most: Paddle out, throw someone on a board, just like Bondi Rescue, and bring them back. The swimmer swims out, and as soon as he gets there, the board paddler can go and pick them up, and the two of you paddle back together. It’s a race. TJ was a swimmer; I was a board paddler. You had to get fourth to qualify, out of eight, to get through each round. We went fourth, fourth, fourth. We were fourth in the quarter-final, and then in the semi-final we won and started to get it together.

HM: How long did you have to get fit?

TH: I lost eight kilos in eight weeks! On the day, the whole beach was full as they’d all heard we’d made the final. In Matrix terms, it was like Neo was fighting Morpheus! Trevor and TJ were in the board rescue together. It was a crazy, weird feeling.

HM: Emotional?

TH: I was standing in the water before the final, with tears running down my face thinking,

“I’m living the dream. I’m doing the Australian Open against the best swimmers and board paddlers in our sport, and I’m doing it with my son. It’s the completion of 20 years of becoming more of the man that I wanted to be”. I was staring down at the water, and these two feet came into my line of sight. I look up, and there’s TJ, with tears in his eyes as well. He says, “I agree, Dad.” I hadn’t said anything, but he was so intuitive, he always has been. I said, “You agree with what?” And he said, “We are living the dream.” Don’t worry about what happens in the final, we’d already won! There is nothing better than this.

HM: How’d you go?

TH: We went into the final, and TJ got out to the can eighth of eight. Young, in his 20s, against all the mature swimmers. I paddled out and I picked him up about fourth. We had the worst turn you could ever imagine – I smacked him in the head, ended up on top of him, but he got on the board and we both laughed. We were back in eighth position again. TJ said, “That was the worst change in history, but don’t worry about it, Dad, let’s go!” There was this little chop pushing us right, and just as I was about to alert him to the fact, he turned his chest and followed the chop right. I realised: “Zip it. He knows what to do.” It was like handing the baton over. He steered us the whole way home, and everything he did, I did. I tracked every stroke. I lifted my chest every time he did. When he was like an albatross with his arms out, I was. When he had his chin down on the board, I had my chin down on his arse! We went from eighth, to seventh, to sixth, fifth, fourth, third, second – and then we ran past two young guys to win the title by half a foot!

HM: Hard to script!

TH: All my childhood heroes were sitting right in front of me. It was a surreal, wonderful, bizarre moment. Everyone was screaming, crying, yelling. It had nothing to do with winning; it was everything to do with purity, truth and love, doing a full journey. It had nothing do with perfection, but everything to do with connection. It so far outweighed every other sporting event of my career, and that was the end of sport for me in that sense.

HM: Father and son – Cat Stevens would be bloody proud of you both. Loved speaking with you.

TH: It’s been a crazy, full circle. That’s why I want to give so much back, because I feel like life has given me so much. Thanks, Hame.

You can find Trevor and his courses at trevorhendy.com

Originally published as Ironman Trevor Hendy turned to a kinesiologist to find ultimate success