How typhoid led to the construction of an architectural gem

A typhoid outbreak caused by locals drinking water from the Yarra River led to the construction of one of our favourite buildings.

Victoria

Don't miss out on the headlines from Victoria. Followed categories will be added to My News.

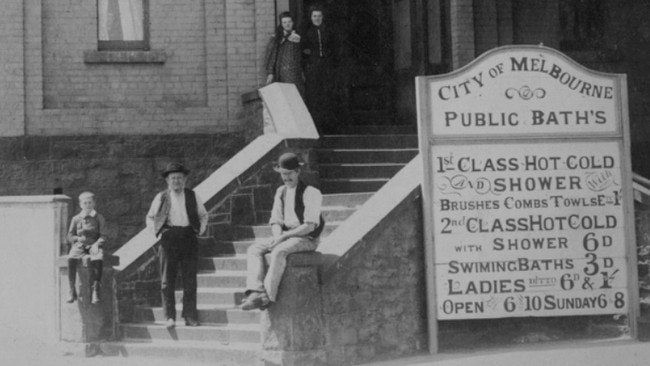

When the first public bath house flung open its doors on a wedge of land on Swanston St, the 100,000-strong population of Melbourne breathed a sigh of relief.

In a time when sophisticated indoor plumbing was rare, the opulent pool and world-class hot showers of the new City Baths were a Godsend for Melburnians who simply needed a wash.

But the squeaky clean tiles hid a filthy secret about early Melbourne’s hygiene.

Until the 1850s, the Yarra River was used as a source of drinking water, and for bathing.

By the time of the gold rush, the river had become so polluted and dirty, it was making people sick. Seriously sick.

Amid a deadly outbreak of typhoid, a disease which killed hundreds indiscriminately, Melburnians were forced to draw up plans for a public bath house, abandon the Yarra as a water source and embark on one of the world’s most ambitious infrastructure projects to bring water in from a new reservoir.

Deadly fever

Typhoid is nasty business.

Caused by bacteria in water or food with fecal contamination, the disease can build in an infected person’s system for 30 days before presenting as a slow-climbing fever.

Then comes abdominal pain, constipation, vomiting, a blotchy rash and sometimes dazed confusion.

In severe cases, the illness is fatal.

So indiscriminate is typhoid, it claimed poor and rich alike, and was believed to have killed Queen Victoria’s husband Prince Albert in 1861.

Some infected people may show no symptoms at all, but can carry the disease and infect others.

In one such case in the US in the late 1800s saw Mary Mallon, an Irish-born cook in New York, infect an untold number of people resulting in up to 50 deaths.

She became known as Typhoid Mary and spent three decades of her life in forced isolation.

A similar case in Victoria reportedly involved a dairy worker who unwittingly spread typhoid through the milk supply.

By the mid 1800s typhoid was a serious problem in Melbourne.

The Yarra River, which had been a water source and favourite bathing spot since the town was founded in the 1830s, was becoming horribly polluted.

Improper disposal of human waste and rubbish in a river still used for drinking water, was a recipe for disaster.

The early city’s notorious open sewer system was also a major spreader of Typhoid.

Taking water from upstream was no use – waste was flowing down from rural towns and carrying Typhoid bacteria with it.

An estimated 20 people were dying each week.

Soon a drastic plan was drawn up.

A new water source for Melbourne would be established at Yan Yean and clean, fresh water would flow via pipes and aqueducts to the growing city.

It would be the largest reservoir scheme of its kind in the world.

The tragedy of James Blackburn

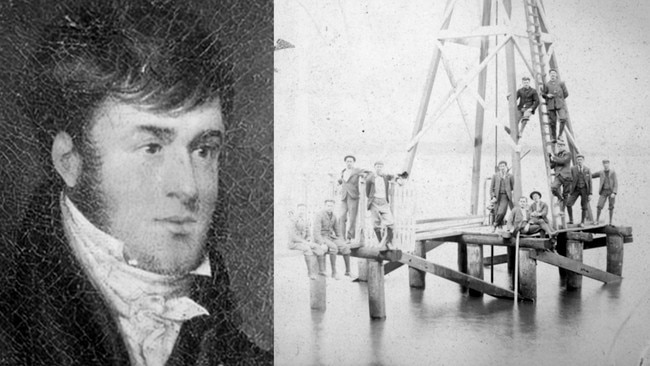

The man whose name was given to the Melbourne suburb of Blackburn was an unlikely hero.

James Blackburn, born in Essex in 1803, was a sewer inspector and public servant who fell on hard times in the 1830s and forged a cheque to stay afloat.

He was caught and sentenced to transportation to Van Diemens Land.

Starting afresh after being pardoned, he became one of Tasmania’s most significant architects designing more than 20 significant buildings.

He later moved to Melbourne where he worked as a surveyor and spearheaded the Yan Yean water scheme.

The plan was to create an artificial reservoir using water from the Plenty river and use gravity to pipe it through Melbourne.

The Plenty was soon deemed unsuitable due to its own contamination so clean mountain water from Silver Creek and Wallaby Creek.

Work started in 1853 and lasted four years.

But it was too late for Blackburn himself.

Before he saw the reservoir, pipes and aqueducts completed, he himself contracted typhoid, the very disease he was working against, and died in 1854.

The disease also killed five of his ten children.

But his legacy lives in the expansive reservoir he designed – then the largest of its kind in the world – which is still used as a water source for Melbourne.

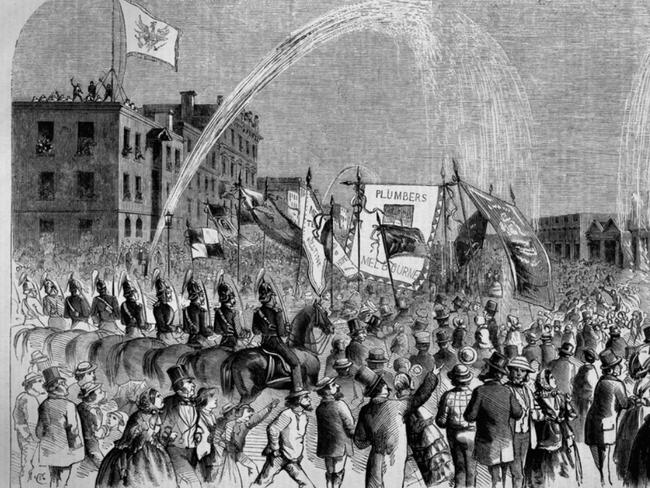

Such was the excitement in Melbourne when the new water source was opened on New Year’s Eve in 1857, crowds gathered to see clean water sprayed in arcs over the street.

In 1860 the new clean water allowed the establishment of the City Baths at a wedge of land at the intersection of Swanston and Victoria Streets.

Newspapers announced that the baths used clean Yan Yean water brought by three-inch pipes in an 80-foot-long pool, where Melburnians could bathe for just a penny.

In the economic downturn of the late 1800s the baths were almost closed for good, but survived and remain on the same site.

The existing City Baths building, which still stands today as an architectural gem, was erected in 1904.

Typhoid persisted as a problem in Melbourne and wasn’t stamped out completely until the 20th Century, despite the long-overdue Melbourne sewerage system built in 1897 and the development of a typhoid vaccine in 1896.

More Coverage

Originally published as How typhoid led to the construction of an architectural gem