Truro Murders: The untold story of the serial killings case

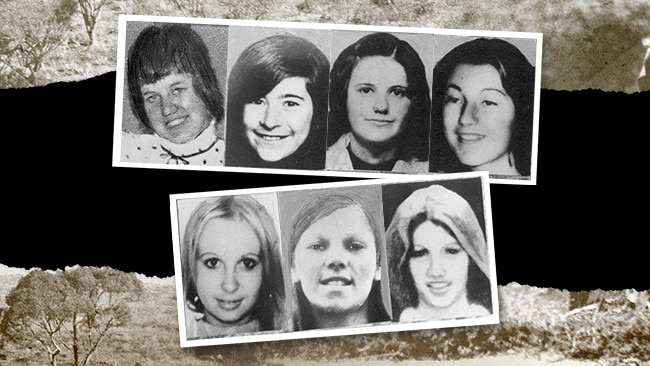

SEVEN young women were kidnapped, raped, murdered and dumped north of Adelaide by a charming young psychopath and his doting accomplice. This is the inside story of how police finally solved the Truro serial killings.

National

Don't miss out on the headlines from National. Followed categories will be added to My News.

AFTER almost five hours of intense interrogation, it took just one question to finally unravel the Truro murders case.

On one side of the small timber table was suspect James William Miller. On the other, Major Crime Squad detectives Glen Lawrie and Peter Foster.

Miller was playing hardball. While he had admitted he was friends with a convicted rapist called Christopher Worrell, for the past few hours he had been denying they had a habit of picking up young women and that Worrell would then rape and murder them.

But as the wily Lawrie continually confronted him with a damning confession he had made to a female friend just two days after Worrell was killed in a car crash a week after the seventh and final murder, Miller finally cracked and rolled over.

At that time — May 23, 1979 — police had already recovered the skeletons of four young women in bushland near Truro, northeast of Adelaide. They were convinced the remains of another three still missing women were in the same area.

Pouncing on Miller’s belated epiphany, Detective Sergeant Lawrie instantly asked him: “Do you know if there are any more bodies laying around out there?”

Chillingly, Miller calmly replied: “There are three more.’’

Detective Sgt Lawrie then asked: “Can you show us where they are?’’

“Yeah” was Miller’s instant reply.

Why police broke the law to find Truro victims

The slain mother Niki never knew

Over the next few minutes Miller, who had just bought himself another three murder charges, told the two detectives enough detail about one body being at Truro and the other two at Wingfield and Port Gawler for them to know he wasn’t pulling their leg. They knew it was all over.

Lawrie asked Miller if he would like to make a statement there and then, complete with all of the details of each murder, or “start by showing us where the bodies are?”

“I think I’d rather show you where they are first and get it over with. That’ll give me time to get my thoughts straight,” Miller replied.

With that response, Lawrie left Miller and Foster in the interview room and went straight to the office of Detective Superintendent Ken Thorsen, his commanding officer, informing him of the breakthrough that had just been achieved.

Although relieved, they both knew the dilemma they were confronted with.

Likewise, Snr Const. Foster realised their legal predicament as he sat with Miller for an agonisingly-long 10 minutes until Lawrie returned.

When he did, Lawrie told Miller that before they took him out he would be taken to the city watch house and charged with the murder of Connie Iordanides — the sixth victim in the killing spree — but the third victim found at Truro. It was a holding charge and another six would follow the next day.

What followed was literally uncharted territory.

Under Section 78 and 80 of the then Police Offences Act, once charged Miller should have either been given police bail — which was never going to happen — or put before a magistrate “forthwith.’’ There was no provision in the Act to remove any prisoner from the watch house to assist detectives to investigate the crime they had been charged with — and yet this was exactly what was about to take place.

The move was unprecedented for police and had the very real potential to derail the subsequent court proceedings.

Mr Thorsen, who retired at the rank of commander in 1987, this week recalled the crucial conversation with Lawrie, and reiterated it was his decision to deliberately breach the Police Offences Act.

He said Lawrie had walked into his office and bluntly told him “we have got a problem.’’

“I asked him if Miller had bolted, and Lawrie replied ‘no.’ Thorsen said.

“Glen said Miller had volunteered to show us where the other bodies are and that after being charged, he should be either bailed or put before the court.’’

Mr Thorsen said he told Lawrie that bail was “out of the question’’ because they already had four bodies directly connected with Miller.

“I say we go for the other three; it will be a very brave judge who excludes the finding of murder victims because we have not arranged a court in the middle of the night, especially if we get him back for court at 10 o’clock tomorrow morning,’’ Mr Thorsen said he told Lawrie.

He reiterated the decision was his and Lawrie and Foster had simply agreed to it.

“I knew what I was doing and why. It was in my opinion the perfect situation to get some change,’’ Mr Thorsen said.

“And it did. Miller’s case led to the amendment of Section 78 to allow four hours to make further investigations and on application to a magistrate, a further four hours. It is now a much more satisfactory investigative tool.’’

Mr Thorsen said his desire to change the legislation had been sparked by a domestic murder at Croydon almost a year earlier.

A man had murdered his de facto and when a patrol arrived he had confessed to two young uniform officers and had even shown them her body. Detectives arrived a short time later and the man was arrested and charged with murder.

At the man’s trial the Judge found the man’s admissions to the uniformed officers were inadmissable because while the man had not been arrested, the officers said they would not have permitted him to leave the scene. The murder charge against him was withdrawn.

The Truro murders are etched in South Australia’s history as one of our worst serial killings. In an eight-week spree between December 23, 1976 and February 12, 1977, seven young women were raped and murdered. The spree only ended by chance — when killer Christopher Worrell, 23, was killed in a car accident in the Southeast on February 19, 1977.

The first victim, Veronica Knight, went missing on December 23, 1976. Her remains were found in scrubland near Truro on April 25, 1978, by locals looking for mushrooms.

Just under a year later, on April 15, 1979, the skeletal remains of another young woman — Sylvia Pittman, were found in the same area by bushwalkers. An intensive police search of the same area over the ensuing days located another two skeletons — those of Connie Iordanides and Vicki Howell.

Following the confessions made by Miller on May 23, 1979, detectives were able to recover the remains of Julie Mykyta at Truro, Deborah Lamb at Port Gawler and Tania Kenny at Wingfield.

Worrell’s accomplice, James William Miller, was convicted of six of the seven murders in 1980 as part of a joint criminal enterprise with Worrell and given six consecutive life sentences with no parole period set. He was found not guilty of the first murder — Veronica Knight — because he argued he did not know Worrell was going to kill her.

In February 2000, he applied to the Supreme Court and then Chief Justice granted a non-parole period of 35 years, making him eligible for parole in 2014. Miller died in custody in 2008 aged 68.

Almost four decades later, the transcript of Miller’s interview with Detectives Lawrie and Foster makes chilling reading.

After being picked up in Gouger St adjacent the southern entrance to the central market, he was taken to an interview room on the second floor of the old Angas St police headquarters.

Lawrie immediately told Miller he and Foster were investigating the disappearance of a number of girls in Adelaide between late 1976 and early 1977 and that four of them had been found at Truro.

His first question to Miller was asking him if he knew Chris Worrell. Miller replied “yeah, I knew of him.’’

The interview started at 4.30pm and for the next four hours and 40 minutes Miller strenuously denied that he and Worrell had ever sighted or picked up any of the missing girls, let alone murdered any of them.

He also initially denied having a conversation with a female friend immediately after Chris Worrell’s death in which he confessed to their murderous rampage. That conversation was the key to unlocking the case when a male friend of the woman, whose name is suppressed, contacted police as a direct result of the first two skeletons being found at Truro.

Despite Lawrie repeatedly grilling Miller about the crucial conversation, it was not until 9.10pm that Miller decided the game was over.

“Can I have a few seconds to think about it?” Miller asked Lawrie.

He was given 10 minutes and the interview resumed at 9.20pm.

“Yeah, well what can I say? If I can clear this up will everyone else be left out of it?” he asked Lawrie, meaning the woman he made the confession to.

“…I suppose I’ve got nothing to look forward to whatever way it goes so I might as well get it all off my mind.

“Yeah, well I guess I’m the one that got mixed up in all this so where do you want me to start?”

Miller went on to reveal there were in fact three more bodies and said he would show the detectives where they were.

When asked what had happened to each of the girls, he washed his denials of the previous five hours away in one shocking sentence.

“I drove around with Chris and we picked up the girls around the city. Chris would talk to the girls and get them into the car and he’d take them for a drive and then he’s raped them and kill them.’’

The watershed moment for the detectives confirmed what they already knew. The pattern had been picked up by veteran detective Bob “Ugger”’ Giles almost a year earlier. He had been tasked by Thorsen to examine all missing persons cases involving young women following the murder of another young woman, Lina Marciano, in March 1978, as part of her murder inquiry.

By the time the second of the skeletons had been found at Truro, Giles had isolated nine missing persons files involving young women — seven would be found to be Truro victims. At that stage the investigation was covert, with just a handful of detectives and senior officers aware of the likely scale of the spree.

While Major Crime detectives were following dozens of lines of inquiry already, the break in the investigation came when a man contacted police after a friend told him of a conversation she had with a man she named as “Jamie.’’ The transcript of her interview reveals the conversation took place two days after Worrell’s death in a car crash in the Southeast on February 19, 1977.

“I was talking to Jamie in the back yard, he kept talking about Chris, he was crying and talking about committing suicide, we talked for some time,’’ she told detectives.

During their conversation Miller told the woman that she “didn’t really know what Chris was like’’ and then admitted that “he and Chris used to pick girls up and kill them.”

“He did not use the word kill, it was some form of Australian slang, I am unable to recall the exact words he used but he made it quite clear that they had killed girls.

“I seen that he was serious about what he was saying so I questioned him further, he said that he couldn’t stop Chris from doing this, that he would pick them up and rape them and then strangle them. Jamie said that he just drove the vehicle for Chris.

“I questioned him further about this and Jamie said that if I didn’t believe him he would take me up to Blanchetown and show me the bodies of the girls they had killed. I got the impression of what he said that there were about six victims.’’

The woman said Miller had told her that just before Worrell was killed in the accident “he got worse and really went ‘mad’ and killed a number of them.’’

There was little doubt Miller was telling the woman the truth. The last four victims — Sylvia Pittmann, Vicki Howell, Connie Iordanides and Deborah Lamb — were killed in a six day spree between Sunday, February, 6, 1977 and Saturday, February 12, 1977.

Foster this week recalled the interview with the woman and how the investigation moved rapidly after “Jamie’’ was identified as a man police knew as James William Just. A petty criminal, he had been in and out of prison for most of his life, mainly for larceny offences. He was using the alias Miller.

Foster said the informant coming forward was the key to unravelling the killing spree, recalling the intimate detailed as he interviewed her with Lawrie.

“We believed she was certainly genuine and she told us he (Miller) had broken down and was crying because Worrell was his true love,’’ Foster said.

“He told the woman that Worrell had killed some girls. From that there was enough to identify Worrell by name and it went from there and the circumstances and timing fitted perfectly.’’

It took little time to establish what had happened to Worrell and ascertain Miller’s relationship with him. Background was obtained on Miller and surveillance was placed on him.

The catalyst for approaching Miller in Gouger St, where he would regularly cash his dole cheque, was when he discovered he was being followed.

“We thought he might bolt. We knew he was a loner so finding him would have been difficult if he had so we made the decision to bring him in,’’ Foster said.

“One of the first things he said when we did approach him was that he knew he was being watched. He seemed kind of resigned to being grabbed.’’

Foster said they had no idea what Miller’s attitude would be when he was approached. They found him to be almost polite. He was cooperative and agreed to accompany them to Angas St. Crucially, he was not arrested at that stage.

Once at Angas St his co-operation continued as the extensive interview commenced.

“He was never aggressive towards us, but he was defensive at the start,’’ Foster said.

“I think there was some relief for him as it went along and it unravelled. There was a relaxation, but there wasn’t a great sigh from him, but he did relax,’’ he said.

Foster said the significance of what was unfolding was not lost on either him or Lawrie.

“I guess in the back of your mind you do want to clear things up, to get a result, but you also want to see those involved obtain some sort of closure,’’ he said.

Foster said it would have been “difficult’’ to charge Miller with the last three murders if they had not recovered their remains.

“It would have been an extremely difficult trial,’’ he said.

“I wonder whether we would have even proceeded.’’

Foster said he can still remember Miller co-operating fully and talking freely during the trip to Truro and the other locations searching for the remains.

“He wanted to get it off his chest at that stage,’’ he said.

“He just kept talking and co-operating. He asked if he could have some tobacco and we stopped at a service station at Smithfield. I think he wanted White Ox, but I don’t remember if he got that.

“He was quite happy to be there. There was no resistance at all and he wasn’t even handcuffed.’’

Surprisingly, at Truro, Miller even stunned Foster when he asked him at one stage: “don’t leave me alone.’’

That was most unlikely to happen. Even though Miller was co-operating fully and actively searching for one of the disposal sites, unbeknown to him, Thorsen had given Foster and Lawrie an order to shoot Miller if he attempted to escape.

Foster firmly believes if Worrell had not been killed in the car crash on February 19, 1977, the murders would have continued.

“They were like raging dogs. They were escalating towards the end and would not have stopped. The momentum was increasing,’’ he said.

Besides the legislative change to give police the power to take charged offenders from the watch-house to assist with any investigation, the Truro case was also the catalyst for change within SAPOL.

It is fair to state the investigation of missing persons reports at the time the Truro victims vanished was a shambles. Once a report was filed, there was little follow-up conducted and they were simply filed.

Sadly, two of the Truro victims missing persons reports were marked “voluntarily absent’’ – a far cry from the reality.

Today, such reports are closely monitored and the likelihood of any similar pattern going undetected for so long is remote.

- This is an edited version of a story first published in December 2016

Originally published as Truro Murders: The untold story of the serial killings case