World waited as doomed Kursk survivors drew their last breaths

When a torpedo exploded aboard Russian submarine Kursk in 2000 it resulted in an emergency that captured the world’s attention.

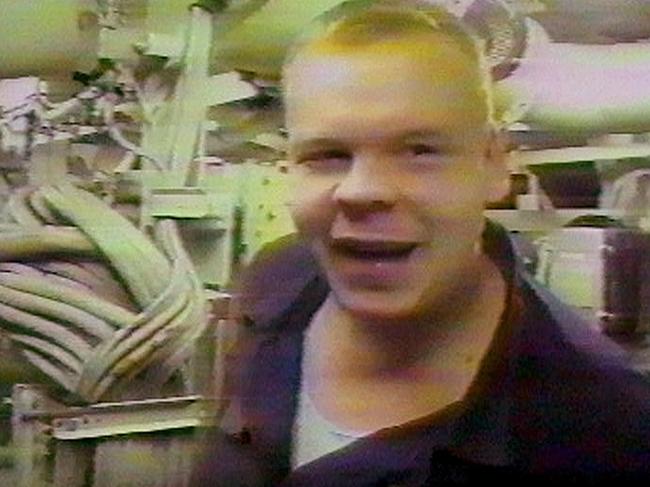

Gennady Lyachin, commander of submarine K-141, gave the order for his men to load two dummy torpedoes. These were like the real thing but minus the explosives and not manufactured to the same strict requirements as real torpedoes. Their target was the battlecruiser Pyotr Velikiy, as part of the Russian military exercise named Summer-X, on the Barents Sea in August 2000. It was the largest naval exercise in a decade and the first since the fall of the Soviet Union.

No one knew the shoddily constructed, or perhaps badly maintained, torpedo loaded into tube number four of the submarine, also known as the Kursk, had an undetected flaw, causing it to leak the volatile chemical high-test peroxide (HTP). When the HTP came into contact with a catalyst, such as copper or brass, it gave off heat and gas that built up inside and blew the torpedo apart, causing a fire on the sub and setting off other torpedoes.

Its hull breached the sub began to sink. Those who hadn’t perished in the explosion or the fire ran to compartment nine, where there was an escape hatch. There they awaited rescue but it never came.

To this day people continue to speculate on whether any of the crew could have been rescued. The response to the emergency was criticised at the time and even Vladimir Putin, who had been Russian leader for about a year, came under fire for what was seen as the failure to free any of the crew of 118 submariners. The controversy has now been revived, with the story of the doomed sub and its crew retold in the film Kursk, opening on August 29 in Australian cinemas.

Kursk was one of the Antey class of submarines (called Oscar II by NATO), planned in the dying years of the Cold War as a counter to US aircraft carriers. The Soviet Union worried about the ability of the US carriers to deliver thermonuclear weapons. The Antey submarines were designed to be large enough to take on a carrier. At 154m long and powered by two nuclear reactors, these would be formidable submarines capable of carrying missiles and torpedoes big enough to take down an aircraft carrier.

Construction began on Kursk in 1990, but before it was finished the Soviet Union collapsed. Instead it became part of the Russian Navy in 1994. But with Russia’s political turmoil and the resultant funding shortages for the military, it was not until 1999 that Kursk went on its first mission, which was to observe US naval movements during the war in Kosovo.

When it was sent to take part in military exercises the next year, its crew had relatively little experience. They were also still carrying HTP-fuelled torpedoes, which other navies had long since abandoned.

The dummy torpedoes had probably been sitting in storage and were in need of maintenance.

When one exploded aboard Kursk on August 12, 2000, setting off four other warheads the sound was detected by seismographs in Norway and as far away as Alaska. Many of the crew were killed by the force of the blast, which battered down bulkheads along the length of the ship. But as the submarine sank to the seabed four compartments contained air pockets. There 23 sailors huddled. They decided against trying the escape hatch, since the chances of survival that way were slim, and they waited hoping for rescue.

Lt-Capt Dmitri Kolesnikov realised he was not likely to live through the experience and in the dim light wrote a note stating what had happened and also composing a goodbye message to his wife Olga.

The detection of the noise of the explosion had alerted US intelligence to the sub’s sinking and many foreign governments quickly offered to aid rescue efforts. But the Russians were slow to realise what had happened and refused all offers of help. Eventually they dispatched their own rescue mission, but were unable to reach the survivors in time.

The last survivors are believed to have perished about four hours after the explosion but while the world watched and hoped the first rescue ship did not arrive in the waters above where the Kursk lay until about 16 hours after the accident. It was another 15 hours before the first submersible made it to the vessel. The submersible made three failed attempts to lock on to the hatch, but when it was finally successful they discovered the hatch was flooded and knew all of the men on board must already be dead.

The Russians tried to cover up the truth of what had happened and blamed the sinking on a collision with an American submarine.