NSW history: Sordid truth behind Blue Mountains’ teenage ghost

Said to appear to travellers on the road to Lithgow, Caroline Collits knew little but neglect and abuse in her tragically short life. Here’s the story behind her haunting.

Today in History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Today in History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

She’s called the Woman In Black — the ghostly figure of a woman dressed all in black who appears on the side of the road at Victoria Pass on the Great Western Highway to Lithgow and Bathurst.

While sightings of the ghostly apparition, with her long dark hair blowing in the wind and her arms raised as if asking for help, have not been reported for years, the story that gave rise to the ghost is a lot more haunting.

Caroline James was born in April 1827, one of six children of William James and Mary Hopkins.

Her parents were reported to be frequently drunk; William ran a sly grog establishment at 20 Mile Hollow, now Woodford, and Mary committed suicide by hanging in 1835 when Caroline was just eight.

Her father, who was in the house at the time Mary hanged herself, was initially arrested, charged, convicted and sentenced to death for his wife’s death, but had the charge overturned and he walked free, and out of the lives of his children who were left destitute.

Caroline and her younger sister Mary, then aged 10 and 12, were sent as servants to the Collits family of Hartley Vale who were the well-known proprietors of a few inns.

In 1840, the girls met former convict John Walsh. He is said to have groomed and carried on a sexual relationship with both young girls.

Mary married him the following year when she was just 11 and Caroline caught the eye of William Collits, one of the sons of the family she worked for and the one his father called a “spendthrift idiot” according to a local paper.

Caroline and William married on November 18, 1840. Caroline was just 13.

The union was neither happy nor long lasting and on December 24, 1841 a newspaper advertisement appeared in which William warned the public not to extend credit to his wife who had left her home “without any just cause or provocation”.

He goes on to say: “I do hereby caution the public against harbouring or giving the said Caroline Collits any credit as I will not be answerable for any debts she may contract.”

Caroline escaped to her sister Mary’s house where it is believed the sisters resumed their sexual relationship with John Walsh.

A few weeks after William’s advertisement, on January 3, 1842, Caroline and William met, together with John Walsh, at Joseph Jagger’s Tavern near Hartley in an apparent attempt at reconciliation.

While William and John were both seen drinking rum and brandy, Caroline only drank “syrup” and at some time throughout the evening the three left the tavern together.

Court transcripts of the night would later recount that John attacked William and that Caroline pulled him off her estranged husband and told him “run, he has a stone and will murder you”.

William did just that, leaving Caroline and John alone.

Just after dawn the following morning, the postman delivering mail to Hartley found the battered body of Caroline Collits by the side of the road on Victoria Pass. It took a jury just 20 minutes to find John Walsh guilty of the murder. He was hanged at Bathurst on May 3, 1842.

Not long after, carriage drivers began reporting their horses would become restless and unsettled when they came near the spot where Caroline’s body was found and others reported seeing the ghostly apparition.

“People love a good ghost story,” says Robyne Ridge, vice president of the Blue Mountains Historical Society.

“And this one is enduring probably because Caroline Collits was also an interesting Mountains person.

“Her story has certainly endured, there was that poem by Henry Lawson in 1891, that I think was terribly inaccurate and I read once that his own mother didn’t want him to publish it.

“And a beautiful mural of Victoria Pass was drawn by Blue Mountains artist Lindena Robb on the side of a toilet block at Memorial Park in Mount Victoria.”

Got a local history story to share? Email mercedes.maguire@news.com.au

THE GHOST AT THE SECOND BRIDGE

Two of the 16 verses of Henry Lawson’s 1891 poem:

“You‘d call the man a senseless fool, — A blockhead or an ass, Who‘d dare to say he saw the ghost Of Mount Victoria Pass; But I believe the ghost is there, For, if my eyes are right, I saw it once upon a ne‘er-to-be-forgotten night.”

■ ■ ■ ■

“She‘ll cross the moonlit road in haste; And vanish down the track; Her long black hair hangs to her waist; And she is dressed in black; Her face is white, a dull dead white; Her eyes are opened wide — She never looks to left or right, Or turns to either side.”

DARWIN’S PRAISE FOR PASS

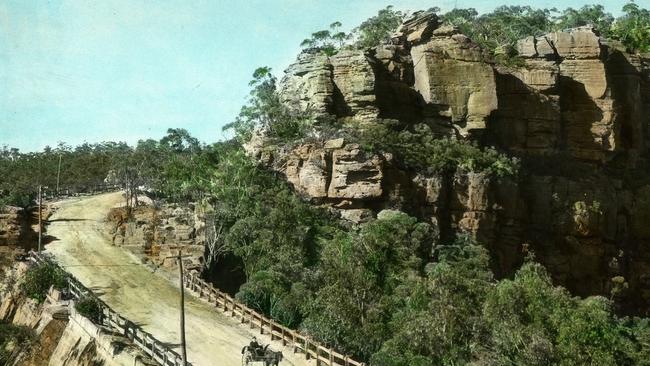

Mitchell’s Bridge is a stone causeway hand-built at Victoria Pass by about 400 convicts. It was named by the Surveyor General at the time, Thomas Livingston Mitchell, and was opened on October 23, 1832.

It was considered an engineering feat at the time, even celebrated by Charles Darwin who commented it was “worthy of any line of road in England” after he travelled it en route to Bathurst in 1836.

It remains part of the Great Western Highway and the main access route to Western NSW.

Family feud robbed former teen convict of her mansion

Margot Riley has spent much of her Covid lockdown walking the streets of Stanmore. And it was during one of these neighbourhood walks that she found a part of the area’s history she didn’t know.

The State Library of NSW curator has always presumed the historic Annandale House, which was demolished in 1905, stood in the suburb of Annandale to which it gave its name.

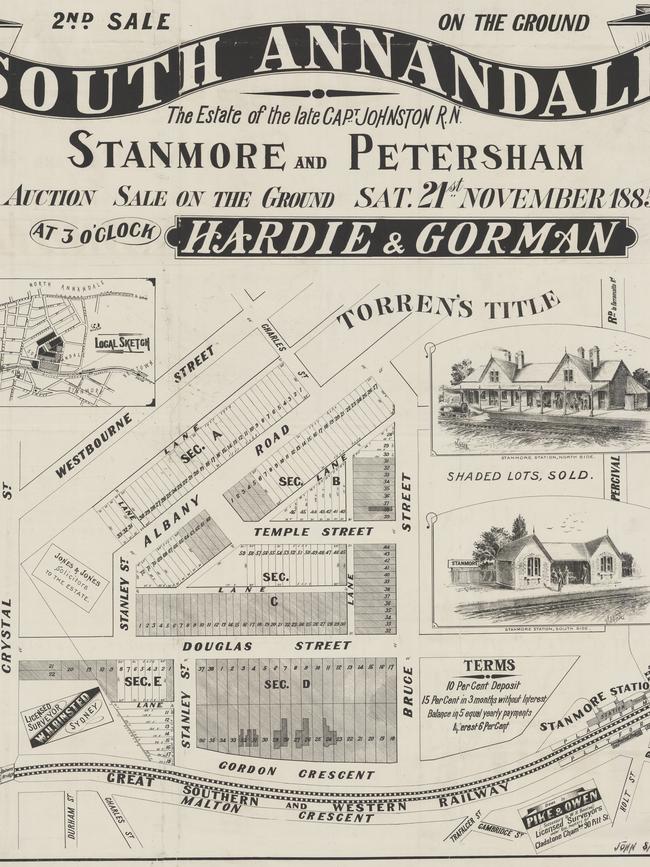

But, researching another topic unearthed historic maps of Stanmore and the fact Annandale House, which belonged to respected Lieutenant-Colonel George Johnston and his wife Esther, wasn’t in Annandale at all, but on what is now the other side of Parramatta Rd, just a few streets away from her home in Stanmore.

“This may be a fact that is known to people, but I never knew Annandale House was in Stanmore,” Riley says.

“I presumed it was located closer to the point in Annandale with views of the harbour, but after I found the map, I walked to the actual location — between Albany Rd and Macaulay Rd Stanmore — and I was so surprised, you would never guess a grand home had once stood there.

“The location was subdivided in the late 1800s and there’s nothing to suggest Annandale House once stood there.”

Annandale House was built in 1799 by Lieutenant-Colonel George Johnston on the 146 acres of land granted to him on the road to Parramatta.

He named it after his Scottish hometown and intended it to be the family home for his growing brood.

Johnston had come out to the colony of NSW on the First Fleet ship, Lady Penrhyn, and it was here he met teenage convict Esther Abrahams. She had been charged with stealing a length of lace from a London draper’s shop the previous year at the age of 15 and sentenced to seven years transportation.

Abrahams was travelling with her newborn daughter, Rosanna.

By 1806, Abrahams and Johnston would have six children together. But two years later Johnston returned to London, court-martialled for his prominent role in the Rum Rebellion and the overthrow of Governor William Bligh.

He would not return to Sydney until 1813. And the following year, he finally made his union with Abrahams official.

In 1820, the couple lost their eldest son, George Jr, when he fell from a horse on John Macarthur’s Camden property. And three years later, George Sr also died, but he bequeathed his estate at Annandale to his wife on the understanding it would transfer to their son, Robert, on her death.

For five years, Esther lived at Annandale House with Robert and two of her daughters, Julia and Blanche.

The family life of the Johnstons would become tabloid news a few years later when Robert tried to get his mother declared insane and incapable of managing the estate.

A witness for the prosecution, ex-convict-turned-physician William Bland, took to the stand to declare Esther “of rather eccentric habits, hasty in temper and with an abrupt mode of expressing herself”.

In an attempt to slam her character, he added it was difficult to “distinguish between excitement caused by drinking and that which is the effect of insanity”.

Esther’s defence countered with testimony from a friend of Esther’s, Jacob Isaacs, who claimed Esther had often sought refuge at his home bruised and beaten as a result of Robert’s violent temper.

In the end, Esther was declared by the court as being “insane but having lucid moments” but Robert was declared “not the heir at law” and so a trustee was appointed to manage the estate and Esther moved in with her other son, David, a pastoralist with an abundance of land in Bankstown and on the Georges River.

Esther died in 1846, aged 74.

From the mid 1880s Annandale Estate was being subdivided and sold off. When the house was demolished in 1905, a local paper described it as “a large cottage with a wide veranda and grand hall” and reminisced about the avenue of Norfolk Island pines which lined the carriageway from Parramatta Rd and which was a landmark of the area.

Got a local history story to share? Email mercedes.maguire@news.com.au

JOHNSTON’S WILD COLONIAL RIDE

George Johnston played a major role in the establishment of a colony in NSW after arriving on the First Fleet ship, Lady Penrhyn.

Shortly after arriving at Sydney in 1788, Johnston was put in charge of establishing a settlement at Rouse Hill and, as a member of the NSW Corps, he helped suppress the revolt of Irish convicts at Vinegar Hill in 1804.

But he is most remembered for his leading role in the overthrow of Governor William Bligh during the Rum Rebellion of 1808. He was sent to London to be court martialled as a result and did not return to Sydney until 1813.

CLOSE TO HOME EVEN IN DEATH

In the 19th century, it was common for the gentry to bury family members in vaults on their property.

When businessman Thomas Holt built his Victorian gothic mansion, The Warren, in Marrickville in 1857, he included vaults intended as a final resting place for his family, but they were never used.

The family vaults on the grounds of Annandale House were used, George Johnston Sr and Jr were buried there along with Esther and other family members before they were moved to a mausoleum at Waverley Cemetery in 1878. And Lieutenant Thomas Rowley was also buried on his estate, Rowley Farm at Camperdown, in 1806.

Riverwood’s link to injured US servicemen during WWII

If you live in Riverwood, you will have noticed many of the street names have an American origin – Washington Ave, Kentucky Rd, Wyoming Place, Roosevelt Ave and Truman Ave to name a few.

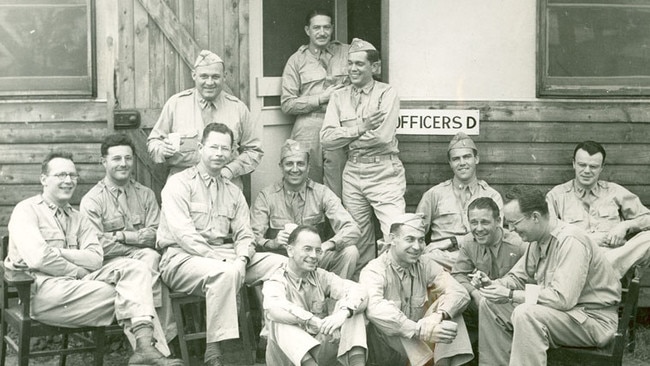

The street names are a modern-day link to a short-lived period in which injured American servicemen were treated there during World War II.

Before the suburb of Riverwood was given its name in the 1950s, it was known as Herne Bay. And during WWII, Herne Bay was the site of the largest military hospital in Australia at the time.

In the early 1940s there was a growing need for a US military hospital to be built in Sydney to treat injured American servicemen.

Before the 118th General Hospital – or the US Military Hospital – was built at Herne Bay in May 1943, injured US servicemen were treated in a section of Royal Prince Alfred Hospital in Camperdown and the Hydro Majestic Hotel in the Blue Mountains suburb of Medlow Bath.

Some were looked after at St Paul’s College at the University of Sydney.

The hospital was built by the Australian government’s Allied Workers Council, set up to organise military construction works during World War II, and was paid for under the Reverse Lend-Lease agreement, a system in which the allied forces supplied military aid to the US.

It was staffed by doctors and nurses from the illustrious Johns Hopkins University Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland.

A few months after it opened, there were 1700 patients being treated at the US Military Hospital but the facility – which had been designed to be used by five hospital units – had a total of 4250 beds in 490 barracks-style buildings. It was in effect a suburb within a suburb.

Herne Bay became the focus of several high-profile celebrity visits during the few short years the US Military Hospital occupied the site.

Then-first lady, Eleanor Roosevelt, visited US patients at the hospital on September 8, 1943, as did comedian and entertainer Bob Hope and the Artie Shaw Band.

General Douglas MacArthur, who was Supreme Commander of the southwest Pacific region from 1942, also paid recuperating US soldiers a visit at Herne Bay.

By October 1944 the main hospital unit left the facilities at Herne Bay bound for the Philippines but some staff and patients remained until January 1945, their use of the hospital precinct lasting less than two years.

The buildings were taken over by the Royal Navy for use by injured servicemen of the British Pacific Fleet and it was during this time, in July 1945, that Princess Alice – Duchess of Gloucester and wife of Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester – paid a visit to recuperating British servicemen at the hospital.

The Duke and Duchess had arrived in Australia earlier that year, with three-year-old Prince William and five-month-old baby Richard, to take up residence in Canberra following the Duke’s commission as governor-general of Australia. More than 9000 patients would be treated at the Royal Navy Hospital.

After the war, the site was taken over by the NSW Housing Commission and the hospital barracks were quickly converted to the Herne Bay Housing Settlement, to answer the urgent need for post-war housing.

The wards were partitioned to house several families in crowded conditions who would share use of the bathrooms and laundries. Over time, public housing apartment blocks and freestanding cottages replaced the former military buildings, mostly located on the northern side of the railway line, while privately owned homes were located on the southern side of the tracks.

In the 1950s, Herne Bay Businessmen’s Association claimed “the present name (of the suburb) has been made infamous by an “emergency” housing settlement bearing the same title” and argued the area needed to split from its public housing roots to help lift its reputation. A competition was held to find a new name and in 1957, the suburb was renamed Riverwood.

Got a local history story to share? Email mercedes.maguire@news.com.au

FROM WAR HOSPITAL TO HOUSING

In 2013 it was announced a $276 million residential project would be built on the site where the US Military Hospital once stood. The masterplanned community, Washington Park, would deliver 780 apartments in 11 buildings released in stages over the next five years. The developer, Payce, marketed the project as a connected community and promoted the fact it would have 11 parks within 1km of it as well as a marketplace with shops and cafes which would give it a village-like atmosphere.

The development was completed in March 2018 and one and two-bedroom apartments now sell there from $539,000.

HERNE BAY’S FLEETING STAY

The suburb of Riverwood has only been known by this name since the 1950s but its history goes back a lot further.

Today, split between Georges River Council and the City of Canterbury-Bankstown, the suburb is the traditional land of the Bediagal people. European settlement dates back to the early 1800s when land grants turned the area into a market garden and small farming community.

Herne Bay railway station opened in 1931, which established the suburb’s original name.

By 1957 the suburb was renamed Riverwood in a bid to distance itself from its post-war public housing past.