Two new books highlight Australian women’s war efforts

Dispensing cakes and cracking codes, the Wasbies and the Garage Girls went to war for Australia. Now two new books are shining a light on their stories.

Today in History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Today in History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The 1945 newspaper advertisement simply read “Seeking Burma Volunteers”. And for hundreds of Australian women it marked the start of their service during World War II.

The ads were looking to recruit a certain kind of woman, one who had some experience living in the Far East and who had a certain “get on with it” attitude to life.

These women would make up the little-known ranks of the Women’s Auxiliary Service in Burma, or the Wasbies as they were affectionately known.

It’s a story that captured the imagination of NSW author Kayte Nunn, who writes about them in her latest book, The Last Reunion.

One of the women who inspired Nunn’s story was Elsa Hatfield, who at 97 is one of Australia’s last remaining Wasbies.

This unit was formed predominantly from British and Australian women to do ciphering and secretarial work in 1942, but they were disbanded and reformed as canteen workers.

On the outside they ran the mobile canteens which served sandwiches, tea, cake and cigarettes to the frontline soldiers, making them the women closer to the frontline than any other females at war. But their most important role was to lift the morale of the soldiers.

“I was living with my friend Margaret Tilley in an apartment in Elizabeth Bay and working as a cipher clerk in Potts Point when we heard of the Wasbies,” Hatfield recalls of the time she volunteered in 1945.”

“Margaret and I joined, we had to go to Melbourne to do fitness tests and be interviewed and then left pretty quickly after that. We went to India where we were drilled and got our uniforms and then sent to Burma.”

Hatfield has a very matter-of-fact way of telling her incredible story, made more so by the fact that by 1945 the plucky young woman, who was born in Shanghai to British parents, had been a prisoner of war since their evacuation from Shanghai in 1941.

After her liberation in 1945, she sailed to Sydney at the urging of a friend and before long was returning to the war, this time as a Wasbie.

“Most of the work I did in the canteen was a lot of fun. We were two or three in the canteen and we would sell baked bean sandwiches and what we used to call ‘char and wads’,” she says, using the slang to mean tea and cakes or sandwiches.

“The soldiers were wonderful, they made a fuss of us all, it was a lot of fun.”

Nunn says she wanted to celebrate female friendship during the war in her book because such a lot is made of mateship among the servicemen but rarely about women.

“There was one story I read in the diary of the women; they arrived somewhere to set up but it was too wet for them to even put up a tent for them to sleep in,” Nunn says of her research.

“They spent the whole night sitting on these tin boxes they put all their personal belongings in with a rain cape over them shivering until morning. But these women had to be so incredibly chipper and cheerful because they had an important morale-boosting role.”

Another recent Australian book release that covers Australian servicewomen during World War II is The Codebreakers by Alli Sinclair.

Her book focuses on the top-secret work of the Australian women of the Central Bureau in Brisbane, which was the Australian arm of the Allied codebreaking unit known as Bletchley Park in London.

“I was doing some research into women, World War II and the Australian Women’s Army Service and a little article came up about a female codebreaker and I thought ‘Wow, how come we don’t know more about these women?’,” Sinclair says.

“I made contact with some of the female codebreakers and their stories, in part, inspired my book.”

One of those inspirational women was Coral Hinds, now 96, of Melbourne. She joined the Army and was posted to Brisbane to work for the Central Bureau.

“We didn’t really know what it would entail but we were told it was very hush hush, and we couldn’t speak about our work to anyone, not even family,” Hinds recalls of the strict command to not speak of their work for up to 30 years after the war ended.

“My parents went to their graves not knowing the real work I did during the war, they just thought I was in signals.”

The Central Bureau worked to decode messages intercepted from the Japanese who were bringing the war closer to Australian shores.

The female unit worked out of a garage on the grounds of Nyrambla House in Brisbane and as such got the name The Garage Girls. The important work of the Central Bureau was credited with ending the war sooner, by up to two years.

But for Hinds, her memories of the war are filled with meeting Alexander ‘Sandy’ Hinds, or the man she still calls “my sweetheart” although he passed away in 2007.

“I went out with him twice but then he was posted to New Guinea and Malaysia,” she recalls.

“But we would write to each other and got to know each other through those long letters. Sometimes though, we would send each other little lines hidden in the encoded messages.

“We had to use ‘padding’ in these messages in order to put interceptors off the real message and when Sandy sent me a lovely letter asking me to marry him, I wrote him back (in the coded message) to tell him ‘yes!’ ”

The Last Reunion by Kayte Nunn is out through Hachette; The Codebreakers by Alli Sinclair is out through HarperCollins

HOW PLUCKY FRESHWATER TEEN RODE WAVE INTO LEGEND

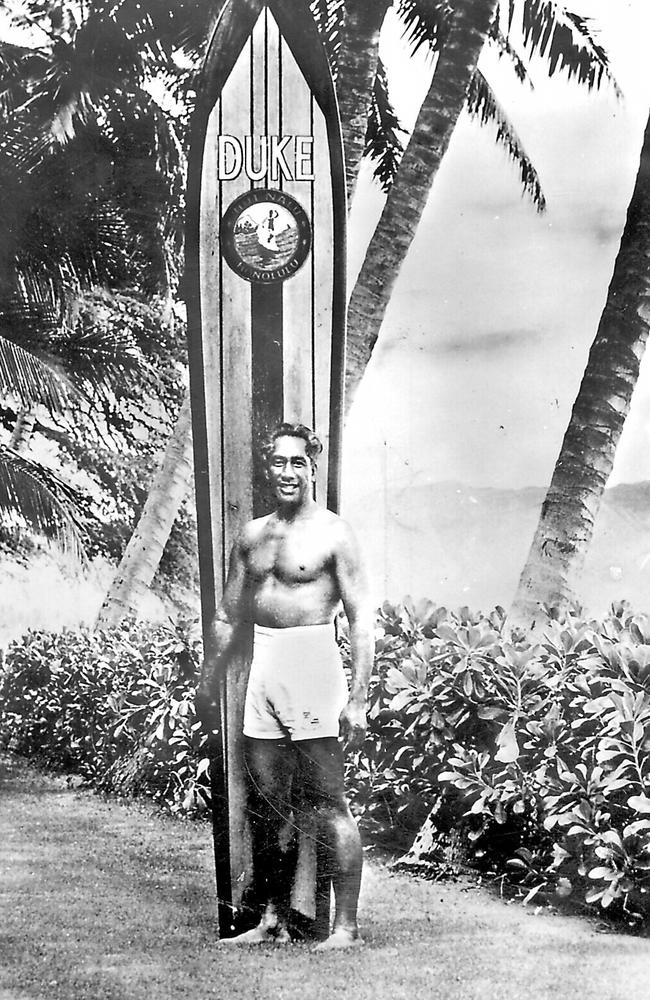

If you live on Sydney’s northern beaches, you have likely seen the bronze statue of Duke Kahanamoku that looks out over the headland at Freshwater.

Whether you know who he is or not, you can presume he is associated with surfing, his statue strikes a legendary pose.

You may even know that it was erected in front of the Harbord Diggers Club to commemorate the Hawaiian man’s summer on the northern beaches in 1915 in which he performed several jaw-dropping displays of surfboard riding.

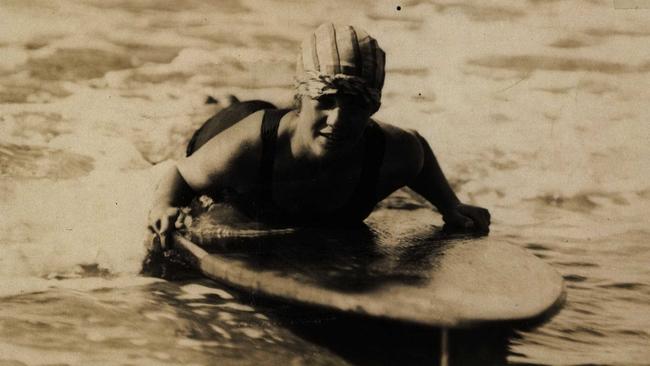

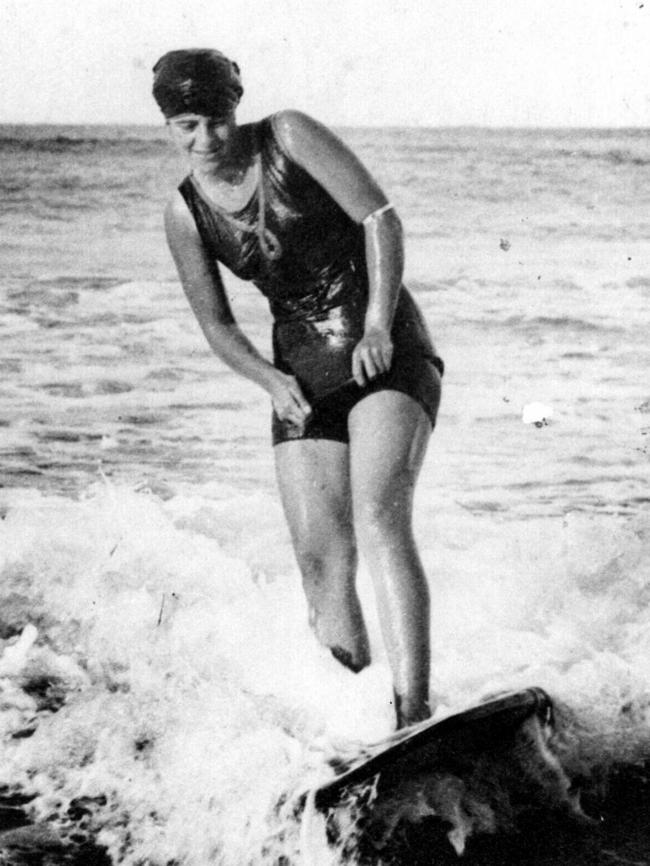

But you may not know the story of the young Sydney teenager, Isabel Letham, who at the age of 15 was plucked out of the crowd that gathered on Freshwater Beach by Kahanamoku to ride tandem on his board.

The plucky young teen, a Freshwater Beach local who was a proficient body surfer — or surf shooter as it was called then — is often mistakenly called the first Australian to ride a surfboard.

She was not, but her few associations with Kahanamoku in the summer of 1915 would go on to shape her long life.

And the legacy of that day can also be seen this weekend just a little further up the Sydney coastline at Narrabeen Beach, where the world’s best male and female surfers are going head to head in the Rip Curl Narrabeen Classic.

Letham was born in Sydney’s north shore suburb of Chatswood in 1899 but her father moved the family to Freshwater while Letham was still a young girl.

Author Phil Jarratt, who wrote That Summer at Boomerang in 2014 about Kahanamoku’s 1915 visit, says the details around Letham’s part in the famed surfboard rides were never properly established and are a matter of great debate.

“She very likely surfed with Duke at Freshwater and maybe even Manly,” Jarratt says.

“But we know for sure she surfed with Duke during a media demonstration at Freshwater Beach on December 24, 1914 and on two occasions later at Dee Why Beach on tandem rides.

“She became a minor celebrity from these few, short associations with Duke and this early media attention certainly helped her get a foothold in the surfing and swimming worlds.”

What is certain is that Letham was not the first Australian to ride a surfboard. That honour likely goes to merchant seaman Tommy Walker, who in 1909 brought back to Sydney a redwood surfboard he purchased in Honolulu.

He likely used it along the NSW coast on his return but in January 1912, he came in on a breaker standing on his feet and on his head at the second annual Freshwater Surf Carnival.

The meetings with Duke in the summer of 1914/15 may have compelled young Letham to seek adventure because later that year, she left school and got a position as the sports mistress at the exclusive Kambala school for girls in Rose Bay.

Unable to join a surf club because she was a woman, Letham would regularly drive to the more obscure beaches of Bilgola and Bungan with her friend Isma Armor and spend weekends surfing and camping together.

But in 1918, she boarded the ship Niagara bound for California and Hawaii, no doubt to look up her schoolgirl crush, Kahanamoku.

They would not meet on this trip but it marked the start of a decade-long career for Letham in the US where she worked as a nanny, learned hairdressing and even had a go at acting, possibly trying to emulate Annette Kellermann a professional Sydney swimmer who became a Hollywood celebrity.

She took a position as a swim mistress at the University of California, Berkeley and later at the exclusive Women’s Swimming Club in San Francisco.

It may be here that she met Kahanamoku briefly as he swam at the baths in San Francisco. They would meet only one more time, in 1963, when Kahanamoku returned to Sydney for a book launch.

Letham returned to Sydney in 1929 after she fell down a manhole and injured her back. She fell into suburban anonymity over the decades caring for her sick mother, teaching swimming and synchronised swimming.

And she continued to surf, well into her 70s. In 1993 she was inducted into the Australian Surfing Hall of Fame and two years later, at the age of 95, she died.

Her ashes were scattered off Freshwater and Manly beaches.

Got a local history story to share? Email mercedes.maguire@news.com.au

RISE OF THE SURF CLUBS

With the daylight public swimming ban repealed in the summer of 1902-03 drowning deaths on Sydney’s beaches spiked.

In response, Bondi Surf Bathers Life Saving Club was established in 1906, followed by Bronte in 1907 and Manly later that year.

Author Phil Jarratt says Manly pioneered the surf rescue boat in 1903 when the Sly Brothers used their boat to rescue swimmers in trouble in the surf.

Bondi redesigned the Life Saving Society’s rescue reel in 1906 and used it to rescue two young boys from the surf that year. One of them was Charles Kingsford Smith, who went on to become a pioneer of flight.

MILLION DOLLAR MERMAID

Annette Kellermann was born in 1886 in Sydney’s inner west suburb of Marrickville.

At six, she learned to swim to help strengthen a weakness in her legs, for which she wore braces. By 15 she had mastered all strokes and she went on to become a champion swimmer, racing in England and France.

She also gave swimming displays and performed a mermaid act and in 1906 at the age of 20 she began performing her act in the US where she became a vaudeville headliner and made several films.

She was a lifelong vegetarian and proponent of swimming for health and fitness. She died in Queensland in 1975, aged 89.

THE ROCKS AXE KILLER’S TRAIL OF BLOOD

Three men struggled with a large wooden sea chest at the edge of Sydney Harbour on a November night in 1844.

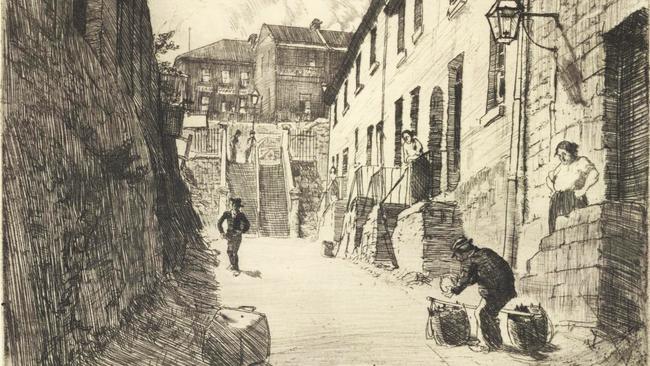

It wasn’t unusual to hire someone to take you across the Harbour from the new Waterman’s Wharf and Stairs in front of Cadman’s Cottage in The Rocks. But something didn’t seem right with these men.

Only one of them could speak a little English and he communicated to the waterman that they wanted to take the chest to the north shore, though exactly where they were going, they didn’t know. They also claimed not to know the contents of the chest.

But the waterman agreed, for two shillings, and they awkwardly manoeuvred the chest down the stairs and on to the boat.

At this time, the waterman caught a strange smell coming from the chest. And then the waterman saw a pool of blood where the chest had sat at the top of the stairs and observed that the threesome were acting increasingly agitated.

The waterman ordered the chest off his boat and called over a constable walking nearby.

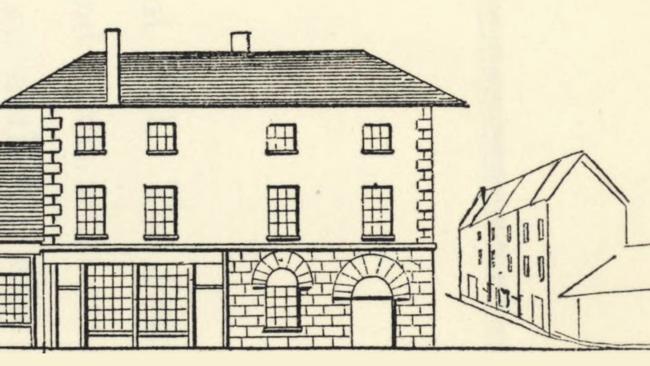

The three French men — John Vidall, James Duval and John Wilson — went with the constable to a residential property called the Terry Hughes Building on the corner of Essex and George streets, where the old Sydney Gaol stood before Darlinghurst Gaol was built in the late 1840s.

They needed to retrieve a key to open the chest.

The constable followed Duval, who had the best English of the three, to the top floor of the building unprepared for the full extent of what he was about to see in the apartment, which stood roughly where the Four Seasons Hotel is today.

“They immediately see signs of a murder,” says Max Burns-McRuvie, historian and creator of walking tours company, Journey Walks, who has been researching this case for a series of talks at Sydney’s Since I Left You bar on April 20 and 27.

“The floor has bloody drag marks across it, there’s a huge pool of blood which has been hastily and poorly wiped with a cloth and there’s a handsaw, a small tomahawk and an American felling axe, all with little bits of flesh, blood and hair attached.

“The fireplace had also been recently used and there was the putrid smell of rotting or burned flesh. Articles of clothing splattered with blood are found hidden away.”

Meanwhile, down by the Harbour, the chest is cracked open by the waterman and water police, and inside they find a bloodstained sack with a human torso and head smashed beyond recognition. The remains were terribly scorched by fire and two legs sawn at the hip were also found.

It was believed to be the body of eccentric debt collector Thomas Warne, who lived in the Terry Hughes building. It was also revealed Vidall was his manservant.

All three men were arrested and taken to the Harrington Street Watch House, the predecessor of The Rocks first police station which wouldn’t be built for almost 40 years.

“The next day the story appears in the papers and it’s huge,” Burns-McRuvie says.

“There are headlines like ‘murder so cruel and so cold-blooded the colony has never seen anything like it’ and the rumours start to circulate.”

The three Frenchmen were revealed to all be whalers who came to Sydney aboard various vessels.

Vidall was rumoured to have been involved in a murder in New Zealand and had been in service to Warne for six weeks. Duval was Warne’s servant before then. Wilson was simply a man recruited to help carry the chest to the Harbour from a pub along the way.

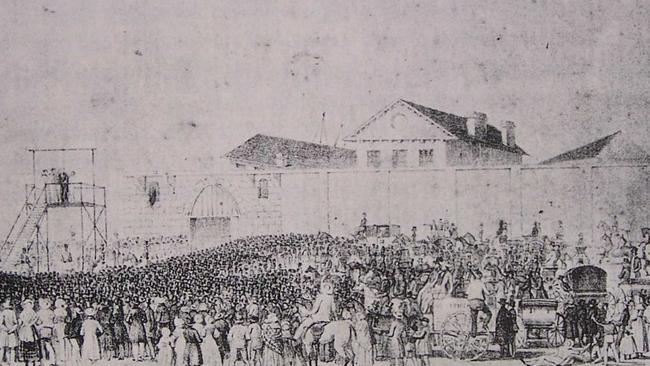

Both Duval and Wilson were acquitted but Vidall faced trial at which he was found guilty of murder and sentenced to death.

A clear motive was never established but in January 1845, weeks before his hanging, Vidall confessed and revealed a heated argument led to the killing.

Vidall was hanged at Darlinghurst Gaol on February 7, 1845 before a crowd of several thousand, including women and children.

Got a local history story to share? Email mercedes.maguire@news.com.au

BRITISH NAVY’S KILLER CAPTAIN

The same year John Vidall butchered Thomas Warne to death, another murder filled the daily newspapers.

Captain in the British Navy, John Knatchbull was sentenced to 14 years transportation for armed robbery, arriving in NSW in 1825, but got his Ticket of Leave in 1829.

In 1832 he was sentenced to seven years at Norfolk Island for committing fraud and again got his Ticket of Leave in 1832. But just two years later he killed single mother-of-two and shopkeeper, Ellen Jamieson with a tomahawk.

Described as a “wretch of the most abominable description” he was hanged at Darlinghurst Gaol on February 13, 1844.

STAY AWAY FROM THE BLACK DOG

John Wilson was drinking at the Black Dog Hotel on Brown Bear Lane, (later Little Essex Lane) when he was recruited by Duval and Vidall to help carry the wooden chest.

This lane was notorious as a magnet for the growing number of whalers and sailors in Sydney.

The Brown Bear pub later became the Black Dog pub, which had the reputation for attracting the worst elements of The Rocks.

It was said sailors even died there from alcohol laced with opium and tobacco and by 1840 the NSW Coroner warned patrons about the Black Dog where 18 inquests into alcohol-related deaths had taken place.

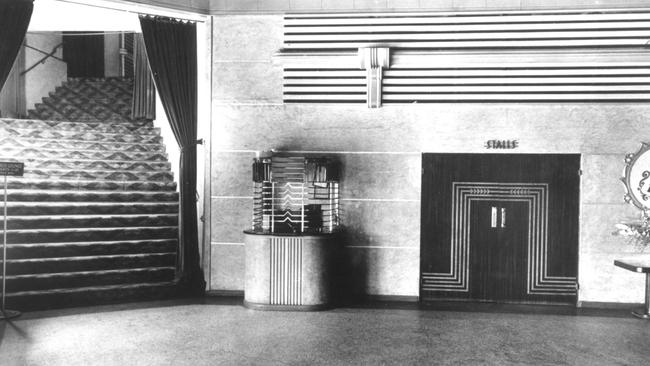

ENMORE THEATRE’S REVAMP DURING SPANISH FLU PANDEMIC

On July 1, 1920, the Enmore Theatre in Newtown reopened its doors with grand fanfare.

The celebrated suburban theatre, where patrons had lined up to catch the latest silent movies starring Mary Pickford and Charlie Chaplin, had undergone a six-month renovation which cost around £30,000. Balcony boxes had been installed, said to be the first in Australia, and seating expanded to 3000.

The theatre owners, brothers William and George Szarka, had used the repeated closures forced on the theatre in a bid to stem the spread of the Spanish flu as an opportunity to renovate their theatre.

Almost 100 years later, the current owners of the Enmore Theatre, Century Venues, did the same.

Sydney’s longest running live performance venue was closed last year as the COVID-19 pandemic forced us all into lockdown and again, the owners used the time to restore the art deco venue just as their predecessors had. The refreshed theatre reopened its doors on February 22.

The side wing balconies were reinstated in accordance with its 1936 architecture and a full renovation of the art deco ceiling was carried out.

It’s a preservation project local historian Chrys Meader feels would get the nod from the original owners, the Szarka Brothers.

“In 1910, the brothers bought an old theatre where the modern-day Enmore Theatre stands today but it was nothing more than a tin shed with logs as seats,” Meader says.

“They were not in the business of running theatres, but they must have seen an opportunity, despite the fact the guy who owned it told them ‘Don’t buy it, I never made any money from it.’ The Szarka Brothers were showmen, they would have refreshment stalls and boxing tents at places like the Royal Easter Show, they were entrepreneurs.”

On October 3, 1912, the old tin shed had been transformed into an imposing structure and was officially opened by the Newtown mayor.

A few months later, the publicity savvy duo took the opportunity of a visit from the NSW governor and his wife, Lord and Lady Chelmsford, to Newtown for the council’s jubilee celebrations, and invited them to the theatre.

More than 5000 schoolchildren crowded the street to catch a glimpse of the event.

“They were never at a loss to make a show and promote themselves, it was quite a thing to have such a visit,” Meader says of the brothers.

“After the visit from the governor, they claimed to be under vice-regal patronage.

“They knew their community, they were born and bred in Newtown and William was an alderman from 1914. And they certainly knew how to build on an opportunity.”

Throughout World War I, the Enmore Theatre prospered but the philanthropic brothers also used it as a source to raise money for the wounded and the Red Cross through benefit performances.

But all that ended in 1919 with the full effects of the influenza pandemic.

In February 1919 all theatres, churches and schools were closed to stop the spread of the flu but an advertisement by the optimistic brothers proclaimed they would soon return with the best pictures on Earth and “meanwhile be inoculated, wear a mask and be cheerful”.

They reopened on March 2 but were quickly closed again on April 6.

“William Szarka led a deputation to the NSW chief secretary, who was also the health minister, with an argument that the opening of the theatres would help allay people’s anxiety,” Meader says.

“And he wouldn’t have been far wrong. Imagine the fear and concern in the community who had survived many years of war just to be dumped into a global pandemic.

“The result is that Szarka got compensation from the government for NSW theatres. It’s my opinion that had Bill not led that deputation they would not have been as successful.”

The Enmore Theatre’s Szarka era ended in 1927 when they sold to Hoyts for more than £100,000, which many saw as a smart move with the Great Depression looming.

Got a local history story to share? Email mercedes.maguire@news.com.au

WILLIAM’S CROWNING GLORY

Im 1917, in order to raise funds for the Newtown School of Arts a competition was held to crown the King of Newtown. You could nominate people as often as you liked, as long as you paid for each nomination.

It’s no surprise William Szarka won and, ever the showman, was carried on a litter from Newtown Town Hall to the Enmore Theatre where he was officially crowned on his stage.

The Sydney entrepreneur was also said to have friends in high places, staying with silent era stars Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks at their Beverly Hills estate Pickfair and enjoying a friendship with superstar Charlie Chaplin.

GEORGE’S HEROIC FINAL SACRIFICE

Just three months after the grand opening of their renovated Enmore Theatre in July 1920, George Szarka was tragically killed by a car.

The story goes that he went to the post office in King St, Newtown to post some letters and he saw a car swerve towards a woman stepping out of a tram.

Szarka ran to push the woman out of harm’s way and was himself struck. News quickly travelled to the nearby Enmore Theatre where his brother William, patrons and workers of the theatre raced to RPA where he was taken to donate blood.

But it was too late.