Mystery still remains over 1959 Richmond Base plane crash tragedy

Eight young, brave and dedicated family men lost their lives just minutes into a routine flight in 1959. And to this day, there is no conclusive cause of the crash.

Today in History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Today in History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Four minutes is all it took for the A89-308 Neptune bomber to crash in a paddock near Richmond in 1959 taking the lives of all eight crewmen on board.

Witnesses on the ground watched as the aircraft, which had been on a routine training flight, caught fire and crashed on a farm less than 3km from the RAAF Base at Richmond.

To this day a conclusive cause of the crash has not been established, despite a lengthy inquiry, but it is accepted that a fault within the engine, not human error, was the cause.

Days after the accident a full military funeral was conducted at the Richmond Base chapel to farewell the brave men of the A89-308 Neptune, complete with a guard of honour as Union Jack-draped coffins were transferred to their final resting place at Rookwood Cemetery.

RAAF historian Martin James says the eight crewmen who boarded the aircraft shortly after 11am on February 4, 1959 would have been a close bunch having flown together on several occasions.

The pilot was Geoffrey Cullen, 35, who was one of the specially-trained men who flew the Neptune from America to Australia eight years prior when the Australian Air Force bought the aircraft. He was married and had two sons and the young family lived in quarters on or near the base.

His young co-pilot was George Holmes, a single man in his early 20s from Warwick in Queensland, whom Cullen had been mentoring.

Robert de Rusett-Kydd was a navigator from Newport on the northern beaches and not long out of training.

Second navigator, John Rock, 24 of Asquith on the Upper North Shore, had lost his mother at a young age and his father less than two years prior to the accident. He had stepped up as the head of his household, which included his two younger stepbrothers Michael, 14 and Peter, 13.

Joseph McDonald was the senior signaller on board that day. He would have worked closely with fellow signallers Frederick Wood, a married man who went by the nickname Andy; Terence O’Sullivan, a married man from Tamworth; and Vincent McCarthy, 35 of Coogee who was the main carer for his disabled mother, Margaret.

It’s easy to imagine that on that sunny summer morning, this crew boarded their flight in good spirits, pleased to be part of the team that would soon escort a squadron of fighter aircraft to the new air base in Malaysia.

On this day, they were testing the Electrical Counter Measures (ECM) equipment and also giving their aircraft an in-air test as it had just come out of routine servicing.

The third task that morning was to conduct currency training, a routine element of all aircrew operations which involved training for events such as typical in-flight emergencies.

Little did they know their simulated emergency would soon turn tragically real.

At about 11.13am pilot Cullen became aware of an issue and called a ‘mayday’ call, alerting the tower at Richmond they would be returning to base. Just a few minutes later he radioed again informing the tower there was an engine fire and he would make an emergency landing at a nearby farm.

Coming down fast, the fire spread to the right wing and it detached, sending the plane into a roll.

The aircraft appeared to bounce a few times along the Hawkesbury River before crashing into the south bank and exploding in a ball of flames.

The crash landing took out some power lines, throwing the local community into a blackout and flinging debris so far it threatened nearby cottages and a local farmer who suffered minor burns.

“This was a big event at the time, it was the first loss of a Neptune aircraft and its entire crew,” James says.

“But the ripple effect the loss of those men caused cannot be underestimated. It also had a ripple effect across the world as a clear cause was never established and that same engine was also used in some commercial airliners at the time.”

A memorial at Rookwood Cemetery and a stained-glass window at the Richmond Air Base chapel honour the memory of these men.

Got a local history story to share? Email mercedes.maguire@news.com.au

BABY TRAGEDY IN DISASTER TOLL

Sadly, there have been several air disasters in Australia’s history, the worst in terms of death toll being the June 1943 crash in which 40 military personnel were killed on a US Air Force B-17 Flying Fortress at Bakers Creek near Mackay in Queensland.

One which may not have resulted in as many deaths but is remembered for its delicate cargo is the Lincoln A73-64 disaster in April 1955 where the crew of four plus a civilian nurse and a two-day-old baby died when their plane crashed into Mt Superbus near Brisbane.

The flight had been a mercy mission to get a lifesaving blood transfusion for the newborn baby on board.

AIR ACE’S HAPPY LANDING AT BASE

The RAAF Base at Richmond, on Sydney’s northwestern fringe, has the distinction of being NSW’s first Air Force Base and the second in the country.

Established in 1925 on a site previously known as Ham Common with the formation of the No.3 Squadron flying unit, it has also been the site of some historic landings, with Charles Kingsford Smith landing the famed Southern Cross there in 1928 after his Trans-Pacific flight.

It was also the location where Jean Batten landed her solo flight from England in 1935.

Today, it is best known as the home of Lockheed C-130 Hercules medium transport aircraft.

BALMORAL’S STAR ATTRACTION FAILED TO LIVE UP TO ITS DREAM

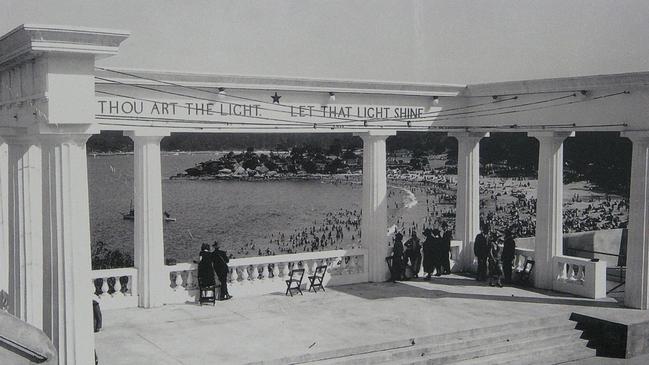

Chris Borough learned to swim in the shadow of the Star Amphitheatre at Balmoral and often played among the ruins of the once-impressive white structure.

He also remembers being on the bus to school and watching a family he thought were “gypsies” emerge from the structure to get the bus to Middle Harbour Primary School.

The Star Amphitheatre, built above Edwards Beach at the northern end of Balmoral, didn’t just fill young Borough’s imagination, it was often whispered about by the locals.

“It was built to witness the second coming of Christ,” people would say.

“It was owned by a cult,” others gossiped.

Borough hasn’t lived in Balmoral for a long time now, but the mesmerising structure that dominated his childhood memories stayed with him and last year he released a book about the Star Amphitheatre called The Light That Never Shone.

“I have such vivid memories of crawling through it as a child,” Borough recalls.

“It was in a state of decay and various bits were crumbling but large parts of it were fairly intact. It was a real feature of the suburb, it stood out from miles away.”

Star Amphitheatre was built by the spiritual group, the Order Of The Star In the East, in 1924.

The Order, which was established in 1911 in India by Annie Besant and Charles Leadbeater to prepare the way for a new ‘world teacher’, was an offshoot of the international Theosophical Society.

But the building of the Amphitheatre was marred by difficulty from the very beginning.

The site chosen for the Amphitheatre was three blocks that sloped down from Wyargine St to Balmoral Beach and was expected to cost around £16,000.

“The cost was meant to come mainly from selling seats in the Amphitheatre from £10 to £100, which back then was a year’s salary,” Borough says.

“It was not so long after the end of World War I and they just couldn’t raise the money and so a loan was taken out to try to complete it.”

The Amphitheatre was eventually finished in 1924 and was perfectly positioned to get the best view out through Sydney Harbour towards the Heads, a fact that could have given rise to the stories about the Amphitheatre being so positioned to witness the Messiah walking on water towards it.

As late as the 1950s newspapers reported it was “built by a religious sect to provide a venue for the second coming of Christ” but such commentary was routinely dismissed by the Order as “fantastic” and “absurd” claiming their real objective was simply to provide a suitable

place for “The Teacher” to address his audience.

It was an impressive Greek Doric structure three storeys high with a stage that overlooked the beach 21m below.

On the beach level there was a library, meeting halls, meditation and tea rooms and it could seat 2000 people with a further 1000 standing.

The structure was meant to be officially opened by their spiritual leader, Jiddu Krishnamurti.

Krishnamurti was a 13-year-old boy whose father was employed as a clerk by the Theosophical Society in India when he came to the attention of Leadbeater who was convinced the boy had a wonderful aura.

He and Besant took the young boy under their wing, educated him in London and groomed him for his role as the spiritual head of the Order.

Krishnamurti did eventually come to Australia in 1925, but rather than give a stirring spiritually uplifting speech, he focused mostly on the Order’s financial woes. He officially disbanded the Order in 1929.

The Star Amphitheatre did hold some performances, plays and lectures mainly, but it never lived up to its anticipated potential.

In 1931 it was sold to Vaudeville promoter George Humphrey Bishop and five years later it was bought by the Catholic Church and it fell into disrepair.

In 1951 it was demolished — less than 30 years after it was built.

Today a block of flats, appropriately named Stancliff, remains on the site.

Got a local history story to share? Email mercedes.maguire@news.com.au

RISE AND FALL OF NEW WORLD ORDER

The Order Of The Star Of The East was established in Varanasi, India, in 1911 by Theosophical Society members Annie Besant and Charles Leadbeater who wanted to prepare the way for a “world teacher” — 13-year-old Indian boy, Jiddu Krishnamurti, who was embraced as the Order’s spiritual leader in 1909.

Despite being well-received in lectures around the world, Krishnamurti began to doubt his role as world teacher and in 1929 he officially disbanded the Order, less than 20 years after it was established.

In Australia, the Order numbered a few hundred who were mostly Theosophical Society members.

TRAM BROUGHT FAME TO BEACHSIDE

A locality in the suburb of Mosman, Balmoral didn’t prosper until the late arrival of the tram line.

Established in May 1922, the Balmoral line was one of the last established in Sydney and linked the community with Wynyard, Chatswood, Lane Cove and Athol Wharf (Taronga Park Zoo).

With the tram line came visitors and this brought about the creation of the popular Promenade, which was completed in 1926.

Balmoral is today famous for its harbour beaches — Balmoral and Edwards beaches — and, along with Promenade, the Esplanade, the Rotunda and the Bathers’ Pavilion, is registered as a conservation area.

DIVORCED MUM’S RADICAL CURE FOR POVERTY

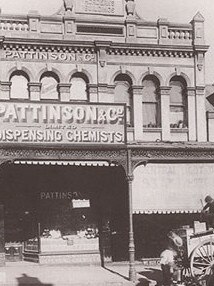

The schoolgirls, men and women who go into Sephora’s flagship store on Pitt St in the Sydney CBD might be surprised to learn that their grandmothers and great-grandmothers probably visited the same building to buy their own cosmetics and more.

Back in the late 19th century and early 20th century, the Victorian Italianate building housed the Washington H Soul Pattinson and Co dispensing chemists. And back then it was so much more than a pharmacy. There was an American-style soda fountain and a “ladies department” run by a nurse.

It was sold by Soul Pattinson in 2018, refitted and opened as Sephora in mid-2020, with retail space on the ground floor and ‘Sephora University’ on the upper floor.

In 1906, Helena Rubinstein opened a salon on the upper floors of the Washington H Soul Pattinson building with chemical manufacturing carried out on the upper floors and a retail space for her skincare line, which included her signature Valaze face cream which she promised could “improve the worst skin in one month”, on the ground floor.

In the days before the internet, sales outside of cities were carried out predominantly by travelling salespeople. And Eliza Elgar, a divorced mother-of-five aged in her early 40s, became one such salesperson.

“The building was quite revolutionary for its time, it had a soda fountain and milk bar with marble top tables and they sold Souls Spartan tonic, which many of the ladies came to drink not knowing it was alcoholic, even the teetotaller ladies,” says historian and author Caroline Hardie, who researched the life of Elgar.

“It was quite the place for women to go and was a respectable meeting place for the suffragettes.

“They also employed a female nurse that women could go to for advice, which in those days was likely code for contraceptives.

“This was the fertile ground that Eliza came into after her divorce in 1910. She had seen women like Rubinstein and suffragettes like Louisa Lawson, Maybanke Anderson and Mary Windeyer around and she wanted to work towards owning a home and escape the poverty she had lived in with her abusive husband.”

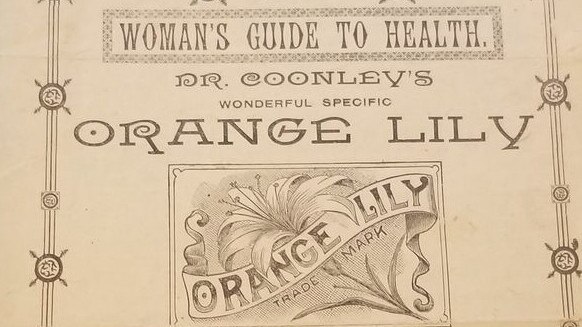

In 1914, Elgar joined the Ladies College of Health and became a women’s health expert travelling to country towns to sell “Dr Coonley’s Wonderful Specific Orange Lily” — marketed as a radical cure for all sorts of female ailments from headaches and backaches to nervousness and languidness.

She also dispensed advice. Ads would run in local newspapers calling Elgar “the skilful lady specialist in women’s ailments” announcing her imminent arrival and the availability of “private” consultations for women.

“She had an amazing itinerary, travelling by train and staying at local country hotels in Cooma, Goulburn, Albury, Wagga Wagga, Moss Vale, Gundagai, Yass — you name it,” Hardie says.

“It must have been exhausting, the ads said she was available for private consultation from 10am to 9pm, and I imagine women were coming to see her for issues they couldn’t see their regular doctors for.

“After these consultations, she would stay up writing romantic short stories which she sold to newspapers under a pen name.”

The advertisements dried up after a few years, possibly indicating Elgar retired from the heavy burden of life on the road. She was into her 50s by this stage.

On her return to Sydney, she bought an acre of land in Carrington St, Wahroonga and her two sons-in-law built her a three-bedroom double brick house.

She was an eccentric older lady who once threw herself in front of a bulldozer to prevent her bush-like streetscape being altered.

She lived out her years writing her stories and growing strawberries that she took to a market-seller in King St.

Elgar died in 1952, aged 87, as a result of burns she suffered from a beauty concoction she was cooking up on her stove.

Got a local history story to share? Email mercedes.maguire@news.com.au

FROM MELBOURNE TO PARIS

Born Chaja Rubinstein in 1872 in Krakow, Poland, Helena was the eldest of eight daughters but immigrated to Melbourne in 1896 where six years later, she opened her first beauty salon.

Her initial skincare line included face cream, a soap, face powder, skin lotion and hair tonic, but she later added questionable products like an electric massager to treat obesity, a vacuum suction to remove wrinkles and a ‘hair destroyer’ as an early depilatory treatment.

She expanded first into Sydney, then New Zealand, London, Paris and the US and died in 1965 of natural causes. The company she started in Australia in 1902 is now owned by L’Oreal.

MIRACLE CURES IN A BOTTLE

Dr Coonley’s Wonderful Specific Orange Lily which Eliza Elgar sold on the road promised to help sufferers of “headaches, backaches, pains in the side and abdomen, rheumatism, nervousness, poverty of blood, languidness etc” but it wasn’t alone in making outlandish promises.

A London ad for Joy’s Cigarettes heralded they’d “afford immediate relief in cases of asthma, wheezing and winter cough”, while an ad for Mendaco Tablets promised to curb asthma in three minutes.

Cod liver oil was marketed as helping “a sickly girl gain 3.5lbs in three weeks” and even Milo was promoted as “tonic food”.

AUSTRALIA’S FIRST SUPERMODEL

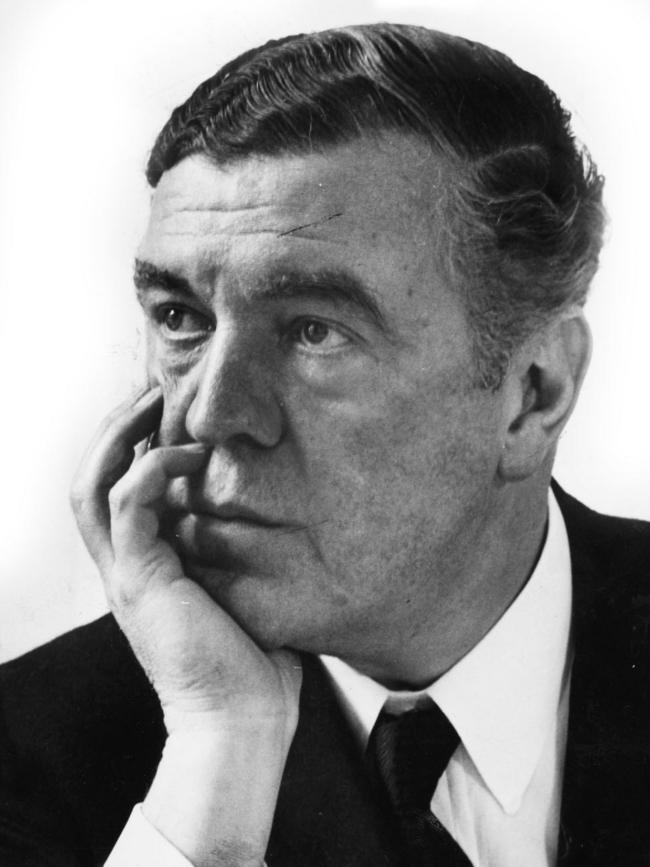

Long before Elle Macpherson was labelled The Body and Lara Bingle asked “Where the bloody hell are you?” there was Margaret Vyner.

You may be excused for asking “Margaret who?” as the blonde beauty from Armidale is all but forgotten these days. But after she made her debut on the Paris catwalks in the 1930s she became a household name in Australia and across the world.

Vyner would go on to star in movies, co-write West End hits and fill the pages of the gossip magazines for her love affairs with famous Hollywood actors.

Michael Adams, author and creator of the podcast, Forgotten Australia, in which he covers Margaret Vyner’s story over two episodes titled Australia’s First Supermodel, says it’s a shame she is not remembered today.

“What fascinated me the most about this story is that most mannequins – as models were called then – were generally anonymous, but Margaret Vyner had a career beyond modelling clothes and was our very first celebrity model,” he says.

“It’s a real shame she is not remembered today, by all accounts she was an amazing woman who led an amazing life.”

Margaret Leila Vyner was born in 1914 to Robert Vyner and Ruby Nicholson. The wealthy family split their time between Armidale in the NSW Northern Tablelands and Sydney’s eastern suburbs and Margaret was educated at the exclusive Ascham School in Edgecliff and later went to the equally exclusive Doone Ladies Finishing School.

After school, she worked in the frock department of David Jones, appeared in some advertisements in local papers and performed in some amateur plays. But she soon realised that if she was to make her mark on the acting world, she would need to head overseas.

On March 31, 1934, she boarded an ocean liner with a friend bound for London.

“They only made it as far as Italy where they got off the ship to make the rest of the journey overland,” Adams says.

“In Paris, they met a client of fashion designer Jean Patou – a prominent couturier who is also largely forgotten today but who was a great rival of Coco Chanel’s – who asked her if she had modelled before.

“He took her on and trained her and in August 1934 she made her debut on the Paris catwalk where she quite literally became an overnight sensation.”

Australian magazines and newspapers heralded “Sydney beauty captures Paris” and “Great triumph of Australian girl in Paris”.

But her working permit was not renewed as the French government wanted to protect the few jobs available throughout the Great Depression for French workers and Vyner went on to London where she worked for Norman Hartnell, the celebrated designer of Queen Elizabeth II’s wedding gown.

Vyner returned to Australia on December 3, 1935 – her 21st birthday – every inch the international model.

British actor and producer Miles Mander was in Australia filming The Flying Doctor starring Hollywood leading man Charles Farrell and Australian actress Mary Maguire.

Vyner was cast in the supporting role of Betty, a society lush, and soon she and the married Farrell fell in love. But the relationship was doomed as Farrell could not secure a divorce from his Catholic wife.

Back in London, Vyner continued to secure successful movie roles and she was cast in a role on Broadway in New York. It was there she met British actor Hugh Williams and the pair married in 1940.

Williams enlisted in the British army during World War II and their finances suffered heavily. By the 1950s Williams declared bankruptcy and it was Vyner who encouraged him to write a play.

In fact, together they collaborated on several plays and at one time they had three in production on the West End at the same time. Their biggest hit was The Grass Is Greener, which they sold to Cary Grant for a small fortune.

In the 1960s they semi-retired to a coastal village in Portugal and, in 1969, Williams died of throat cancer. Vyner succumbed to emphysema in 1993, aged 78.

Got a local history story to share? Email mercedes.maguire@news.com.au

BIRTH OF A CREATIVE DYNASTY

Margaret and Hugh had three children – Hugo, Simon and Polly – who all went on to make names for themselves in the creative arts.

Hugo Williams, born in 1942, became a celebrated British poet, publishing his first collection in 1965. His 1999 book, Billy’s Rain, won the prestigious TS Eliot prize and in 2004 he received the Queen’s Gold Medal for Poetry for his Collected Poems.

Simon, born in 1946, became an actor, best known for his role as James Bellamy in the 1970s television period drama Upstairs Downstairs.

And Polly, born in 1950, followed in her mother’s footsteps as a model and actor.

JEAN PATOU’S ELEGANT LEGACY

Jean Patou was once described as the most elegant man in all of Europe and his designs were innovative. In the late 1920s, he reinvented the popular “la garconne” look that had dominated throughout the decade by raising the dropped waistlines and simultaneously dropping hemlines to the ground.

He was also an innovator in the fragrance world, his perfume Joy once named the most expensive in the world. After his sudden death in 1936 the House of Patou lived on with designers such as Karl Lagerfeld, Jean Paul Gaultier and Christian Lacroix at the helm until it closed in 1987.