The day the Wallal expedition of 1922 travelled to remote Western Australia to test Einstein’s theory

A REMOTE part of Western Australia became the most important place in the world for physicists for one brief moment in 1922.

Today in History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Today in History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

IN 1922 a remote part of Western Australia became one of the most important sites in the world for physicists. A solar eclipse was due to occur in September, which would provide a unique opportunity to test part of the Theory of Relativity, outlined several years before by Albert Einstein.

The optimum viewing point was an arid spot on the coast of the Kimberley region known as Eighty Mile Beach, but the only things nearby were a telegraph outpost and Wallal Downs cattle station. Many scientists were sceptical of whether the delicate equipment would survive being transported to this far flung shore, but thanks to the determination of an Australian academic and the help of indigenous Australians, the Wallal expedition of 1922 confirmed some aspects of Einstein’s theory. Photographs of the expedition are part of a new exhibition Gravity and Wonder, opening at the Penrith Regional Gallery tomorrow.

In his 1704 work “Opticks”, Isaac Newton predicted that light, any other particle, should be affected by gravity like and over the next two centuries scientists had been trying to accurately predict how much light would be deflected by gravity. Even Einstein tried in 1907 and 1911, laying down the challenge to scientists to observe and accurately measure how much the rays of starlight were bent around the sun, which should be possible during a solar eclipse, when only the corona of the sun was visible. Weather and the outbreak of war thwarted several expeditions.

But in 1915 and 1916 Einstein proposed his general Theory of Relativity, which provided the physics that allowed him to more accurately calculate the deflection of light around an object.

High hopes were held for a British expedition in Principe Island (in the Gulf of Guinea off Africa) and Sobral (in northeastern Brazil) in 1919. But clouds and problems with instruments interfered with results.

That is why scientists were so keen on heading to Australia to observe the 1922 eclipse. But when the ideal spot was determined as Eighty Mile Beach, a stretch of coastline and scrubby desert in the Kimberleys they were doubtful. Many thought it too far to transport the equipment and observers.

However, Alexander Ross, head of mathematics and physics at the University of Western Australia was far more enthusiastic. He could see that the location in the north of Western Australia was less likely to suffer weather problems so disputed claims that the area was inaccessible, pointing out the telegraph and cattle station.

Prime Minister Billy Hughes offered government support including rail transport for expedition members across the country, a naval escort, a donkey train and help with establishing a base camp. The team would consist of a group of scientists from Britain, Canada, India, the US and Australia, including Ross. Among them was esteemed American astronomer William W. Campbell, from California’s prestigious Lick Observatory, whose arrival in Sydney in early August was reported with some excitement in the papers.

A group of 20 sailed out of Fremantle on August 20, aboard the Charon. They landed at Broome where they picked up a party of Indian scientists, and sailed to Eighty Mile Beach on a schooner towed by a steamer. They arrived at the beach on August 30 bringing ashore supplies and equipment through rough surf. A large group of local indigenous people, the Nyangumarta, gathered to watch the spectacle and offered their help.

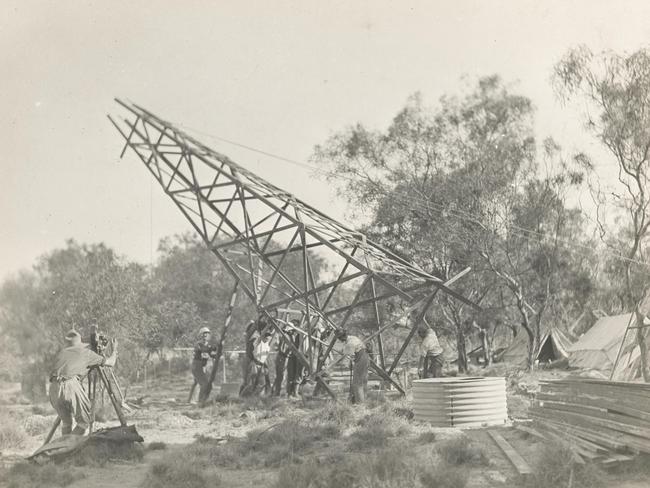

Wooden towers had to be erected to accommodate the large cameras used to capture the images of the eclipse. Again the Nyangumarta pitched in. It took several days to align the cameras, but all of the effort was worthwhile.

The expedition to Wallal was one of three mounted to Australia. A University of Adelaide team was sent to Cordillo Downs in northeastern South Australia while an expedition under the aegis of Melbourne Observatory, the Sydney Observatory, the University of Sydney and the Astronomical Society of NSW was sent to Goondiwindi in Queensland. Under a pristine sky, on September 21 the Wallal team was the only one to successfully capture the observations, despite the fact that the nautical almanac they were using was out by 16 seconds in predicting totality.

The results showed that Einstein’s predictions of light deflection had been very accurate, thereby providing some confirmation of his theories.

* Gravity and Wonder, Penrith Regional Gallery, 86 River Road, Emu Plains; tomorrow to November 27, free