Colossal Laboratories says thylacine extinction could be reversed by 2028

The minds behind a project to reverse the extinction of the Tasmanian tiger expect to see success as early as 2028, and they’re already looking at places to release the creatures. Find out where.

Tasmania

Don't miss out on the headlines from Tasmania. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The thylacine could be resurrected as early as 2028, according to the team determined to bring it back, and the group are already looking at possible sites to release it.

Professor Andrew Pask, from the University of Melbourne, has been exploring the idea for 15 years, and now his vision has the backing of American company Colossal Laboratories and Biosciences.

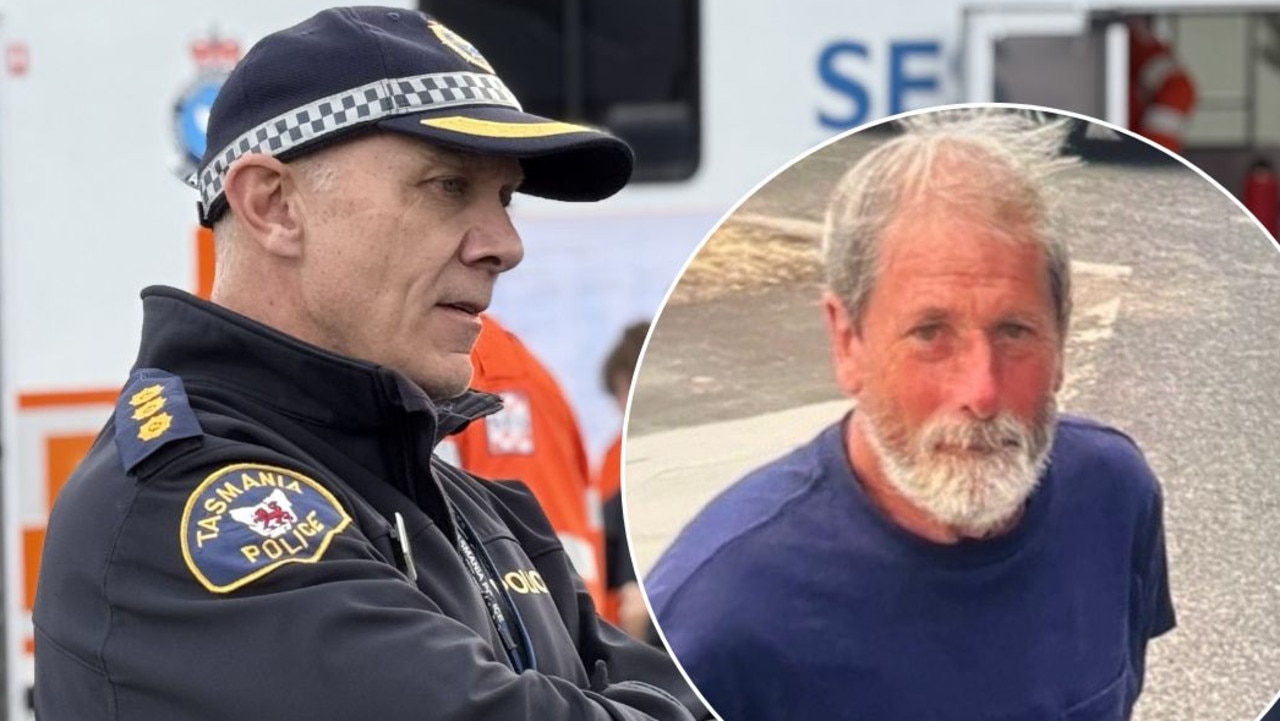

On Tuesday the pair took the idea to Tasmanians, meeting with stakeholders in Hobart to begin consultation.

“The feedback today was overwhelmingly positive,” Colossal CEO and co-founder Ben Lamm said.

“What we’re looking for from the Tasmanian people is collaboration, giving feedback, understanding what’s important culturally, what’s important ecologically.

“We just started engaging with the Australian government in the last two months.”

The group has not yet engaged the state government about the project.

It has begun consulting with landowners, including on locations the thylacines could be released to down the track.

“We work very closely with the team that runs London Lakes, it’s about 5000 acres in central Tasmania,” Mr Lamm said.

“They’ve been doing an incredible job of putting up camera traps, reintroducing wombats and quolls and building this incredibly diverse ecosystem and actually removing invasive species.

“London Lakes could be a really interesting potential location, there’s a couple of others we’re starting to look at.”

Professor Pask said the process of releasing the animal into the wild would be gradual.

“You would not release the first thylacines that we make,” he said.

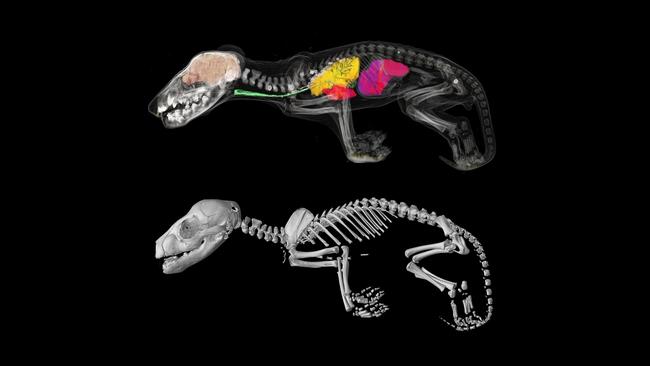

“You keep them in a confined area, you study very carefully the impacts they’re having on the species numbers within those particular numbers and then you progressively release into larger areas, keeping them contained until you’re really sure they would have that ultimate positive benefit.”

The team has also been in conversation with the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery to collect old thylacine teeth for the project.

“There’s really good DNA we’ve now discovered in teeth, before that we were using the skins,” he said.

“There’s also very few pups collected, preserved in ethanol … there’s one we call the miracle pup we found at a museum in Victoria, that has extraordinarily intact DNA.

“We’ve been able to get really good sampling from over 50 specimens.

How much will it cost and when will it happen?

The company says it’s not seeking funding from governments, because it already has the funds for the project.

Mr Lamm said Colossal had raised more than $225m for its extinction projects, to bring back the thylacine, the woolly mammoth and the dodo.

It’s estimated the thylacine part of the project will cost an “eight figure amount”.

“It’s the largest investment by anyone into marsupial developmental biology,” Mr Lamm said.

Mr Lamm said Colossal had set the target of 2028 for the woolly mammoth, and though that project began earlier, it was likely the thylacine would come first.

“The benefit with the thylacine is we’re looking at 13 and a half day gestation versus 22 months in an elephant,” Mr Lamm said.

“It’s likely you could see a thylacine before 2028 but we’re not committed to a hard timeline.”

The team will consult with Tasmania’s Aboriginal community

Aboriginal advocate Peter Rowe, who is also the Derwent Valley Council’s Indigenous adviser, will take the idea to Tasmania’s Aboriginal community.

“About a year and a half I’ve been involved, today’s the first time they’ve gone public, now I will go talk to Aboriginal groups and explain what’s happening and also take the feedback,” Mr Rowe said.

“I think [consultation] is important, the thylacine’s seen as such an iconic symbol and cultural item for all Aboriginal people, not just in Tasmania, it’s also throughout Australia.

Mr Rowe said he believed many in the community would supportive of the plan.

“It was the apex predator for the Tasmanian environment … losing the thylacine was a devastating impact and now we’ve got impact of other animals, like cats,” he said.

“We’re all about being part of the land and looking after the land and environment. To be able to restore some element of the natural balance is something all Aboriginal people are always concerned about.

“I think they’ll be very excited.”

What does the thylacine mean to Tasmanians?

Derwent Valley mayor Michelle Dracoulis reached out to the team and helped facilitate the first meeting with Tasmanians about bringing back the thylacine.

“I approached the group myself when I learned about the project, I recognised this was something that tied in closely with our identity as Tasmanians,” she said.

“My thinking was we need to be part of that story, it’s not something that needs to be done to us, we need to be a part of this story.”

Ms Dracoulis said the thylacine had a special place in the minds of many Tasmanians.

“It’s something that lives in our imagination, it’s something everyone can describe, even though there hasn’t been one in living memory,” she said.

“It’s devastating to think we lost that because of ignorance.

“I very much like the idea that one day we will have tigers back in the Derwent Valley.

“As many people would know, the last one was caught in the wild, near Maydena and it would be lovely to think they were back out there doing their job in the environment.”

Ms Dracoulis said many in her community were already curious about the project.

“In my region, it’s more a case of disbelief, not quite understanding how and if it’s going to happen, how it’s funded, what the intention is,” she said.

“I understand it’s going to raise a lot of questions, I understand that it’s going to raise a lot of emotion, it’s tied in very much with identity, it’s tied up with sense of place, I think if anyone does have concerns it’s important they voice that.”

More Coverage

Originally published as Colossal Laboratories says thylacine extinction could be reversed by 2028