Sydney’s shameful asylums: The silent houses of pain where inmates were chained and sadists reigned

TORTURE, murder, beatings, sexual abuse and death. The stories behind some of Sydney’s best-known asylums uncover the institutionalised horror that shamed the city for decades.

News

Don't miss out on the headlines from News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

SYDNEY’S asylums are haunting monuments to a shameful chapter in our criminal and medical history.

Shut away from a public that was fearful of the “wild-eyed lunatic”, the city’s poorly-funded asylums became a dragnet that would catch the forgot, the poor, the criminal and, of course, the mentally ill.

But it would also catch unsuspecting, otherwise sane people in its web. People who were officially stamped lunatics because of ‘domestic trouble’, ‘religious excitement’, ‘love affairs and seduction’, ‘nostalgia’, ‘sun stroke’, ‘overwork’ and ‘sexual intemperance’.

Download The Daily Telegraph and Sunday Telegraph app for your smartphone or tablet to get the full story.

APPLE: DOWNLOAD THE APP FOR iOS

GOOGLE PLAY: DOWNLOAD THE APP FOR ANDROID

And once a patient was admitted, their complaints about grave injustices were often simply noted by doctors as further evidence of their delusion and insanity. For many, there was no escape.

There were plenty of success stories, but for many others primitive electric shock therapy, murder, rape, neglect and outright sadistic brutality on the part of staff made Sydney’s asylums nothing more than silent houses of pain.

GLADESVILLE MENTAL HOSPITAL (FORMERLY TARBAN CREEK LUNATIC ASYLUM)

ANY place built on top of more than 1000 anonymous corpses would send a shiver up anyone’s spine.

Tarban Creek Lunatic Asylum was Sydney’s first purpose-built asylum, opened in 1838 at the aptly named Bedlam Point, on the shores of the Parramatta River.

It was hoped the asylum doctors would befriend their patients, not chain them up, and help them become normal citizens once more.

But the end of transportation between 1839 and 1840 meant the aged, infirm, invalid or lunatic convicts, who had no means of support and had been in chains most of their adult lives, were sent to asylums like Tarban Creek. Built for 60 patients, by 1844 there were 148 inmates.

On July 1, 1850, a Medical Board of Inquiry convened to investigate the deaths of two patients.

“In this instance, on May 23, 1849, a maniacal patient fractured the skull of another patient with a chamber pot,” Dr Terrence Smith writes in a 2005 University of Western Sydney study.

“The injured patient died six or seven weeks later.

“The Medical Board of Inquiry’s Report laid the blame for the deaths of the two patients squarely on conditions at the asylum.

“Another serious incident occurred during 1843 when (it was) discovered two of the male convict keepers were sexually abusing female patients, which resulted in the keepers’ imprisonment on Cockatoo Island.”

The 1000-plus corpses under the asylum illustrated the stigma that mental health had at the time.

Families refused to pick up their relatives’ bodies when they died, forcing the institution to create mass graves. Other deaths will forever remain a mystery, with many patients having no relatives or friends to speak of.

MORE NEWS

PERSON OF INTEREST DRIVES PAST WILLIAM TYRELL BUSH SEARCH

Employee deaths were also common. In 1884, Senior Attendant Robert Colvin died of peritonitis caused by being kicked in the abdomen by a patient.

In 1889, Attendant Hubert Small died when his skull was fractured by a patient wielding a broom.

When Turban Creek changed to Gladesville Mental Hospital in the 20th century there were still problems.

A doctor resigned in 1954 after being spotted smoking a cigarette while delivering electric shock therapy to a patient.

Nurses referred to the shock treatment as “being put on the Bunnerong”, a reference to the now closed Bunnerong power station at Matraville.

Another 1954 report accused staff of burning the head of one female patient after zapping her with too many electric shock treatments.

“While perfectly sane, only suffering from depression and too many sleeping tablets, she was subjected to so much violent shock treatment which frightens her so badly, like others she tries to resist,” a newspaper article from November 24, 1954 read.

“On one occasion three men patients were brought in and nearly strangled her, tearing her clothes badly.

“She was later thrown in the refractory block and is there at present forced to sleep in a straitjacket at night the same as others in that part, many times strapped to a seat in the daytime.”

CALLAN PARK — ROZELLE

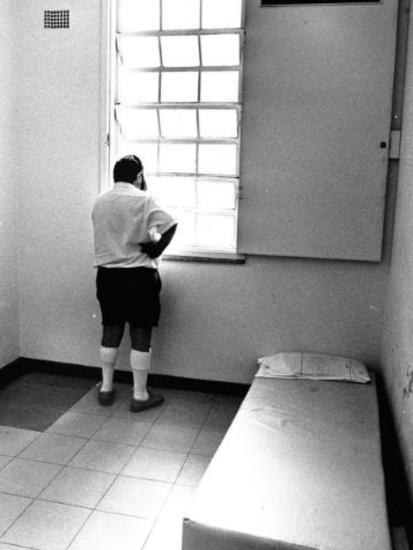

WITHOUT the luxury of antipsychotic drugs, Sydney’s early asylums were designed to keep the “lunatics” out of the public eye.

Callan Park was opened in 1878 with the desire to do just that, but also with the hope of improving patient’s lives through the relatively new medical discipline of psychiatry.

“In the pre-asylum, pre-19th century situation they used to chain these poor devils up and they were like wild animals,” Sydney University medical historian Dr Milton Lewis said.

“The early view of them was that they were not really human beings, but half animals.”

Despite the organisation’s best efforts, Callan Park soon became overcrowded, underfunded and forgot, creating a toxic climate where sadistic nurses thrived and good souls suffocated.

“These so called nurses treat patients most cruelly. They are mechanical, inhumane creatures,” one ex-patient wrote in the newspaper Truth on July 29, 1900.

“I once had my hair pulled until my nose bled. I have seen the nurses twist patients’ arms behind their backs until they cried out in pain, and bump their heads against the stone wall.”

Throughout the years there were accusations of elderly patients bashed with a leather strap filled with studs, patients forced into straitjackets for more than five days at a time, and pills being forced down patients’ throats with the full knowledge they would have a severe allergic reaction.

Perhaps one of the saddest stories is that of 40-year-old Phillip Bowman, admitted in 1900.

Bowman was an unemployed father suffering financial problems and found by local authorities to be “labouring under the hallucination that his children were going to starve.”

Authorities said his stay would be short, but three days into his stay his jaw was shattered in “a most mysterious manner”.

An independent post-mortem found “the fractured jaw had never knitted and the jagged ends of the bone were in a state of decay”.

He had the injury for more than two months before he died, with no proper medical treatment given. It was concluded that starvation hastened his death.

“This poor unfortunate being must have suffered the most agonising torture during that time until death came to terminate his misery,” the article said.

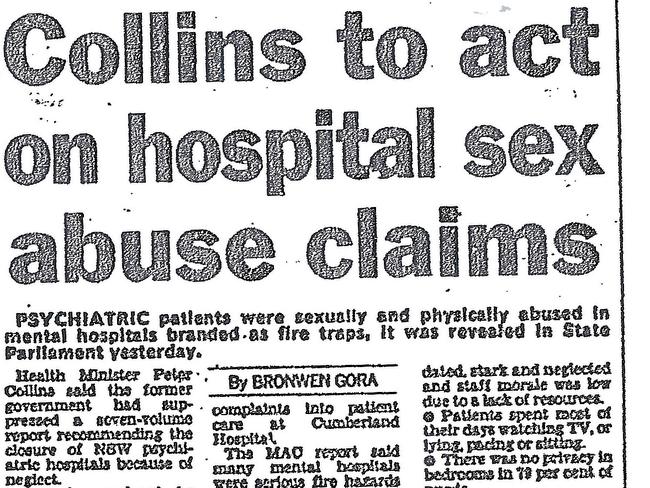

The 1961 Royal Commission into Callan Park Mental Hospital found there was a group of male staff who were bashing, starving, verbally abusing and failing to clean patients.

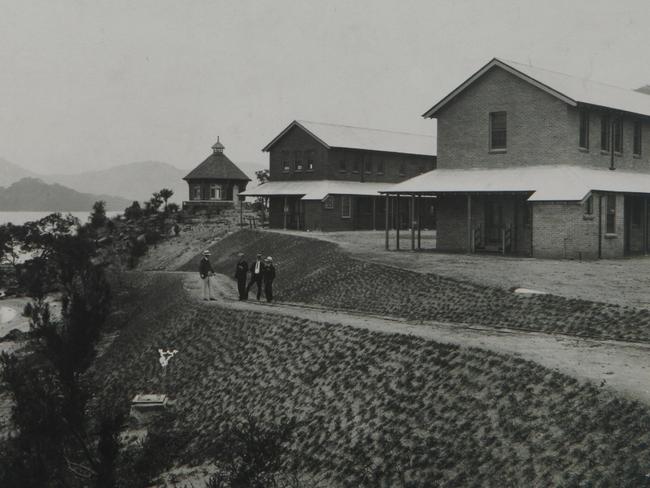

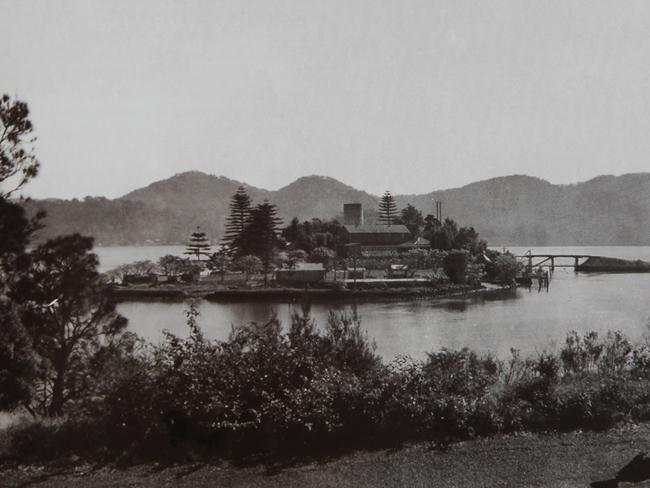

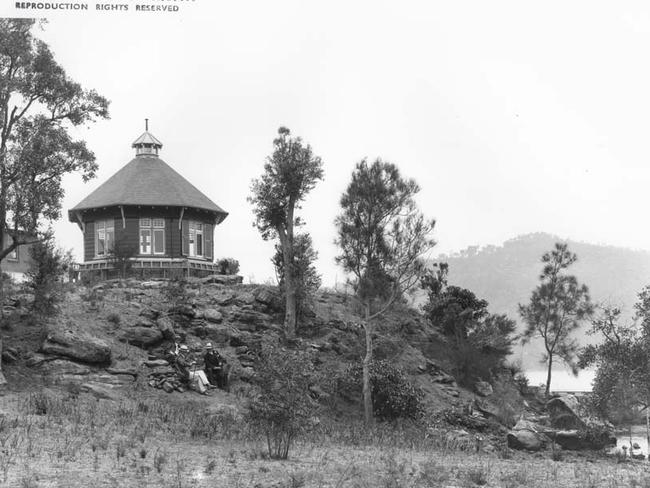

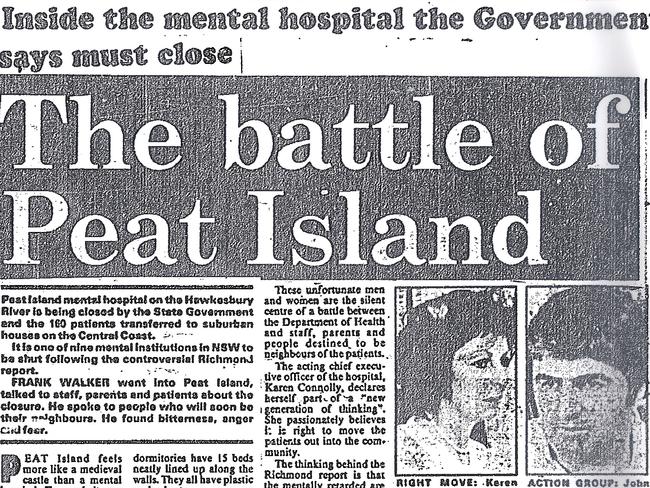

PEAT ISLAND — BROOKLYN

TORTURE, murder and mass graves made this island for the intellectually disabled an isolated place of horror.

Since this tiny speck of land on the Brooklyn River took its first 20 patients in 1911, it has seen a string of mysterious drownings, sexual abuse allegations and murders.

With archaic attitudes towards mental health and disability, many young boys were abandoned on the island after WWI and forgot by their relatives.

Those boys died as old men having never left the island.

In 1924 reports surfaced that inmate William Pfingst admitted to killing another inmate, Harold Besley, by hitting him with a stick, tying him up with a bag over his head before dropping him in the water where he eventually drowned.

Sixteen years later an eight-year-old boy was found floating in the Hawkesbury River in 1940, and an 11-year-old boy asphyxiated inside a linen bin made of iron.

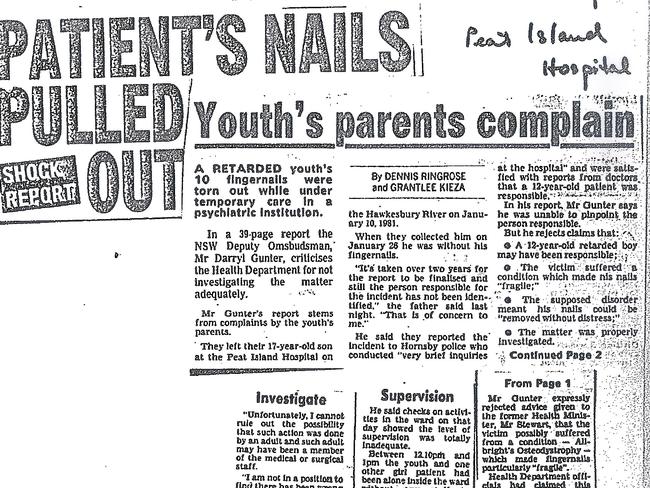

In 1981 a 17-year-old male patient had all of his fingernails brutally ripped out. Health authorities were later slammed for not properly investigating the matter.

But local historian Tom Richmond said there are many unexplained deaths that will remain that way because of a cone of silence that existed around the island and the wider Brooklyn community.

He said many of these people’s stories will be forgot by history.

“It’s horrendous when you look at the number of burials in Brooklyn Cemetery,” he said.

“There is about 300 people were buried there, but only two headstones. They were burying them on top of one another.

“These people, whose families had abandoned them, are all buried in unmarked graves.”

Mr Richmond said before the island was closed in 2010 many inmates came to love it.

CUMBERLAND LUNATIC ASYLUM — PARRAMATTA

CRIMINALLY insane patients were a big feature of this asylum, with its location near the now-decommissioned Parramatta Gaol.

One of Australia’s most notorious serial killers, Albert “Mad Mossy” Moss was housed at Parramatta Asylum for seven years until 1933.

It is believed the career criminal carried out his first murder in January 1933, shortly after he got out of the asylum.

He killed swagmen who were travelling through the bush and on unpopulated roads. When in prison, Moss claimed he had killed at least 13.

Moss was prone to feigning insanity in order to avoid prison and instead go to an asylum.

The state psychiatrist who examined him said that Moss was “the most brutal and cunning’’ killer he had ever examined.

Moss died in Long Bay Penitentiary hospital on January 24, 1958.

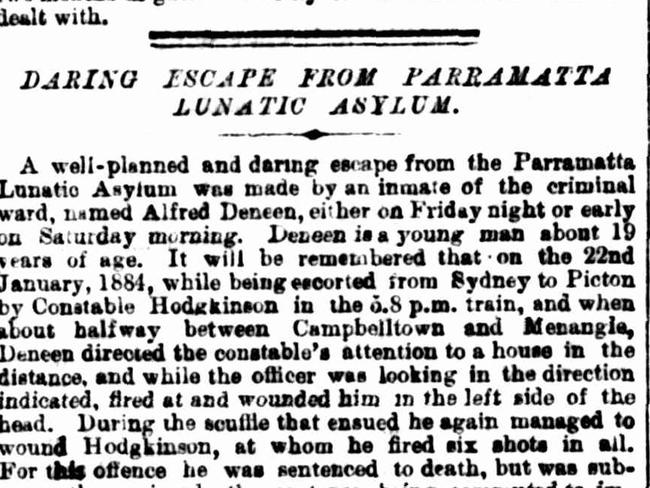

Parramatta Lunatic Asylum was also the site of one of the great escapes from an asylum.

On Tuesday 17 March 1885 newspaper articles collected by the National Library reported that Alfred Deneen escaped from the asylum.

Deneen had been sentenced to life imprisonment for attempted murder of a police officer.

He cut through the bars of his cell and squeezed between 10 inches of bar and stone.

He made a 20ft rope out of strips of sheet, dropped them from his second-storey cell to the ground outside, scaled two walls, and was gone.

But the most famous inmate was Arthur Augustus Oakes, the ‘honeymoon killer’ who murdered his new wife, Mona Beacher.

Newspaper Truth, in an article from January 26, 1936, tells the story best.

“Tortured through the slow-passing years by the nightmare torment of his ghastly crime, Arthur Augustus Oakes, the honey moon murderer, has at last gone out of his mind and has had to be removed to the Parramatta lunatic asylum,” it reads.

“Eleven years ago Oakes perpetrated one of the most fiendish and cruel deeds in the history of criminality.

“He committed bigamy with a pretty Newcastle girl, laughingly took her from her parents on a honeymoon.

“Then he killed her and slept with the corpse. No wonder the memory of that blood-chilling night drove him mad!

“Subsequently he cunningly hid his trail. But he was just as cunningly tracked and trapped by Detective-sergeant Fergusson, an episode of real detective work.

“During the past twelve months, during which his mind has steadily become more and more unhinged, Oakes has caused warders anxiety at the Goulburn and Long Bay jails.

“His screams during the night were reducing the warders and prisoners to a state of nervous torment so that there were nights during which the whole jail would be awake.

“Above the uproar would be raised the shrill, terrified cries of Oakes ... ‘Mona; Oh, Mona, forgive me, let me die ... M-o-n-a!’”

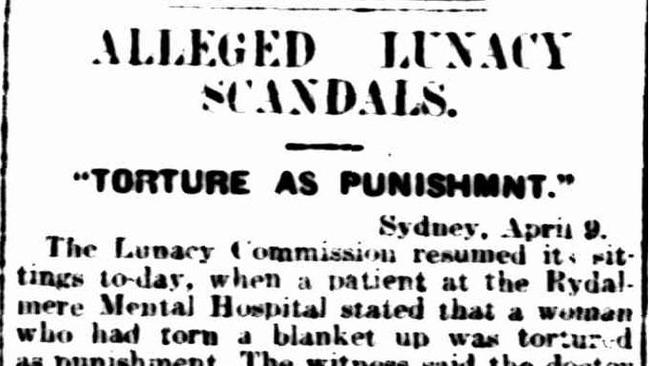

RYDALMERE PSYCHIATRIC HOSPITAL

ELECTRIC shock treatment was a common practice in Sydney asylums, but sometimes workers used electricity for torture not treatment.

Two ex-patients told the Lunacy Commission in 1923 that they had seen electric batteries applied to the feet of patients at Rydalmere Psychiatric Hospital.

The patients couldn’t speak or walk afterwards, so the doctors then decided to “stimulate the patient with an electric coil”.

Another article stated the coils were applied to the patient’s feet and ears as punishment for tearing a blanket up.

Rydalmere was established as an asylum in 1888 in the old Protestant Orphan School building.

About 17 per cent of deaths in Rydalmere were due to an unexplained disease described as ‘maniacal exhaustion’, according to the University of Western Sydney.

There were plenty of deaths, however, that were brutal in their simplicity.

Rydalmere asylum patient Mary Masterton, 50, was found lying in her room bloodied, battered and bruised on January 8, 1925.

It was found fellow patient Alice Perrin had dragged Masterton around by the hair before repeatedly smashing her head against the floor.

Perrin was said to be “suffering from acute mania” when she carried out the killing, and therefore was found not guilty of murder by way of insanity.

Another patient also met a violent end at the hands of a fellow patient. Cecil Crouch, 23, was strangled in his bed by an inmate on January 16, 1928.

In a chilling postscript, the patient who killed the young man was believed to have said after the killing: “I settled the boy”.

The inmate then attempted to commit suicide by cutting an artery in his arm.

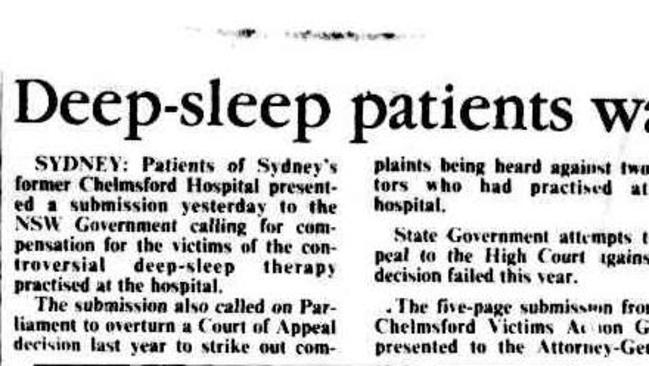

CHELMSFORD PRIVATE HOSPITAL — PENNANT HILLS

CHELMSFORD will forever and always be remembered as the site where more than 20 patients died and countless others’ lives were ruined under the watch of chief psychiatrist Dr Harry Bailey.

Dr Bailey administered “deep sleep” therapy at Chelmsford between 1962 and 1979.

In order to supposedly cure depression, addiction, blindness and other conditions, he would put patients into a coma for up to 39 days via a cocktail of barbiturates.

Then he would administer electro-convulsive therapy — often without patient consent, anaesthetic or muscle relaxants — with devastating outcomes.

Mainly because of the barbiturates, fit and healthy patients would leave either dead, or with pneumonia, kidney damage, bowel haemorrhages, deep vein thrombosis and other ailments.

Daily Telegraph journalist Janet Fife-Yeomans covered the story at the time and co-authored Deep Sleep: Harry Bailey And The Scandal Of Chelmsford.

She said the most terrifying thing about Chelmsford Hospital was how ordinary it all looked. “It was not an asylum behind high walls; it was an ordinary-looking former house in a suburb,” she said.

“The treatment there also sounded so simple, along the lines of how a good sleep does you good. They were the days when nurses were not expected to question doctors — the doctors were always right.”

Ms Fife-Yeomans said a nurse, Rose Nicholson went into the hospital undercover to work and secretly photocopied documents which revealed what was going on, including that patients were not giving informed consent.

“The medical authorities began investigating and professional charges were laid and Bailey was criminally charged,” she said.

“But it all came to nothing in the courts. No-one was disciplined and Bailey killed himself.”

After a chorus of public outcry about the mental health system, the NSW Government eventually closed the state’s large asylums in favour of smaller, more specialised services.

The 1982 Richmond Report was the beginning of the end for the asylum, ending a painful chapter in Sydney’s history.

LISTEN TO AUSTRALIA’S No1 COLD CASE PODCAST

Eight Minutes is a special investigation podcast series into the cold case murder of David Breckenridge. Listen to it on your smartphone now

► CHAPTER ONE: WHO KILLED DAVID BRECKENRIDGE?

► CHAPTER TWO: WHO WAS DAVID BRECKENRIDGE?

► CHAPTER THREE: WHY POLICE STOPPED DAVID’S CREMATION

► CHAPTER FOUR: LOVE TRIANGLE EXPOSED DURING INQUEST

A toxic climate where sadistic nurses thrived and good souls suffocated

A toxic climate where sadistic nurses thrived and good souls suffocated