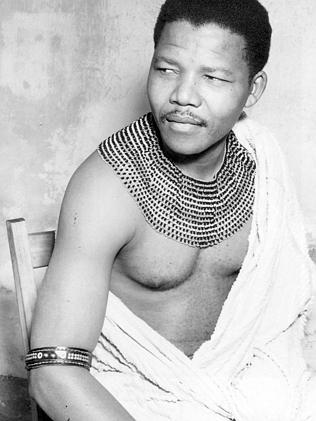

NELSON Mandela has begun another journey, back to the beginning, a place of open skies and valleys of South Africa's Eastern Cape, to where a baby was born in 1918 and named Rolihlahla.

Mandela's tribal parents knew something about destiny. Roughly translated, Rolihlahla means troublemaker. His final burial place, long a subject of conjecture, looks likely to be a thatched mansion that is the ancestral seat of Mandela's tribe.

It is where three of his deceased children have been buried and it is the site of a museum built in Mandela's honour.

It has been described as a 'remote" site. It won't be for long, not now. Mandela's resting place is certain to become one of South Africa's major tourist attractions. And not just for domestic visitors.

Mandela, who at 95 lived far longer than anyone could have expected, nestles alongside Mother Teresa and one of his own heroes, Mahatma Gandhi, in the international mindset as a keeper of wisdom.

He had promoted the ideal of his people's freedom ahead of his own freedom - indeed, ahead of his own life - in a court trial in 1964. Mandela chose to believe in what seemed at the time to be unbelievable.

His courtroom flourishes put Mandela beyond the usual roll calls for nation changers. He stood to be a martyr of unusual eloquence - the judge, within the swirl of a brutal and oppressive regime, had powers to sentence Mandela to death

Yet it was the next 27 years that cast Mandela in a Biblical light. He was jailed for sabotage and related crimes against the state. His mother died in 1968, then his son died in a car crash in 1969. He would break rocks and endure long stints in solitary confinement.

When he was released in 1990, he shuffled as though his joints had locked up. Here was a paradox, an old man and a fresh start, the kindly embodiment of a cruel society of which he had been removed for so long. Mandela was thrown by the media microphones pointed his way, the "long, dark furry object(s)", as he called them. He wondered if they were new forms of weaponry.

He had chosen to remain in prison for his politics, despite many conditional offers of release. His example grew, not despite his absence from public view, but because of it. His suffering became the foundation fable of South Africa's struggle against apartheid.

Throughout his public life, especially since his release in 1990, he never lost a charisma that defied the many privations of his struggle - that, and a gentle sense of fun.

Yet those looking for clues to Mandela's subsequent greatness in his childhood will find scant evidence. His village lay at the end of a 30km dirt road.

His parents could neither read or write, though they were esteemed among the Xhosa-speaking Thembu people. His father was an adviser to the Thembu royal family.

Mandela inherited some of his father's stubbornness, but he was not raised to question his nation's prejudices.

After his father died, he was placed in the care of the acting regent of the Thembu people. He was educated, as he put it, to become to a "black Englishman".

One day, as he detailed in his 1995 autobiography, Long Walk To Freedom, he hoped to attain the highest station a black man could covet - a clerk.

Once, when a friend dismissed a white strangers demand on the street to fetch some stamps, Mandela had watched on in awe. Such defiance.

At university he marvelled at fighting words, such as freedom, but he was slow to embrace the wisps of discontent. The rhetoric awoke something within, but it also frightened him.

He had listened to warnings against activism. It was dangerous, he was told. He'd end up broke and in jail. His family would suffer.

"It's nice that young people still come to see an old man who has nothing new to say," he greeted a visitor to his Johannesburg home in 2010.

In the early 1940s, Mandela was a lawyer in training. Once, he was dictating a note to a secretary in a Johannesburg firm when a client walked into the office.

The secretary gave Mandela some coins and pointedly told him to get her shampoo.

He went and got the shampoo. He didn't think to say no.

Nelson Mandela was black. The secretary was white. Doing her bidding, despite her subordinate role, was assumed in a society where white supremacy was enshrouded in law.

At the time, Mandela had other worries. His suit was more patches than cloth. He often walked six miles to and from work to save money on the bus fare. His weekday meals could be counted in mouthfuls.

Mandela was yet to connect - and subsume - his personal hardships to the poverty and discrimination inflicted upon millions of black South Africans.

There was no epiphany in Mandela's political awakening. His agitation was instead inspired by "the steady accumulation of a thousand slights, a thousand indignities and a thousand unremembered moments''.

"I simply found myself doing so, and could not do otherwise,'' he would say.

His aims would match those of many other political heroes. But few others were forced to persist for 50 years, for a cause that for most of that time appeared doomed. And few could persevere against such injustice with such unyielding grace.

Mandela wanted democracy and equality for all South Africans. His graduation to activism mirrored the South Africa states rise in oppressiveness.

After 1949, codes of segregation grew more strident. Mixed marriages were outlawed, as was interracial sex.

The Group Areas Act separated where blacks and whites could live, and legalised forced removals.

The State obsession with race extended to racial categories, with diabolical consequences. Siblings, for example, came to be classified in different racial groupings.

As a lawyer, and with a swagger, Mandela subverted principles of white supremacy, even while many white witnesses refused to answer questions from a black lawyer.

His activism, under the African National Congress umbrella, heightened as the ANC grasped that long-held legal efforts to wrench change had failed.

It understood that members must be willing to be jailed. It organised illegal strikes and demonstrations. The personal perils worsened.

In 1950, Mandela sheltered behind a wall being thumped with bullets. Eighteen people were killed in that Freedom March demonstration.

He attended activist meetings at night, debating the theoretical conundrums - and threats to safety - that always abounded.

Should the ANC unite with the Indians, who were persecuted but not as harshly as blacks? Should Communist sympathisers who shared the common white enemy be welcomed into the cause?

Mandela read political theories. Photos of Stalin, Churchill, Gandhi, Roosevelt hung on walls at his home.

And he continued to plot when he was banned from meetings (including his child's birthday party), and sometimes popped up unannounced to speak at public gatherings.

Mandela copped his first serious sentence in 1952. Riot deaths mounted, even though protesters adhered to peaceful principles.

State policies hardened in response to the protests. Edicts pronouncing on race defied all conventions of logic or human decency. Yet Mandela had stopped being overwhelmed by the State's seeming invincibility.

"Now the white man had felt the power of my punches and I could walk upright like a man, and look everyone in the eye with the dignity that comes from not having succumbed to oppression and fear,'' he said.

His rebellious streak extended to an acceptance that violence (without bloodlust) was the only strategy that could win freedom concessions.

Underground, leading a militant wing of the ANC, he was known as "Black Pimpernel" in the months before his arrest in the early 1960s. He wore disguises to elude capture: he was dressed as a chauffeur when he finally was.

Mandela's fighting rhetoric prior to his prison term didn't get aired much in his later life. It didn't suit an elder statesman who spoke of reconciliation: it did, however, suit an earlier era of killings and disappearances.

Mandela himself spoke of climbing a "great hill" when freedom was won - only to discover that more hills needed climbing.

He became the country's first black president in an era of drastic change. His grace alone did not unpick the knot of issues faced by South Africa, but it cooled outbreaks of violence and revenge attacks.

The prism of apartheid was a cover-all indictment of South Africa, but it hid social, economic and political challenges that continued to fester after its abolishment.

"I had come of age as a freedom fighter.''

Mandela was a better saint than politician. For one, he admitted that he too slow to tackle the health crisis (his own son died of AIDs in 2005) while in office. That his and nation's path was uncharted, and that he lost his best years to confinement, can't be overlooked.

His first wife, Evelyn, accused Mandela of abandoning his family.

"The whole world worships Nelson too much,'' she once said. ``He's only a man.''

His oldest daughter Maki Mandela resented her father while she grew up. He was never there, she said. Another child (of Mandela's six children from two wives) once said that Mandela was a father of a nation, but not much of a father to his children.

His esteemed mantle also shielded his mischievous way in private. Former US president Bill Clinton used to dread calls from Mandela. Clinton always hung up feeling compelled to obey the latest Mandela edict.

Mandela's greatness was cast before his presidency, within the confines of prison, where he did not succumb to despair.

After his release, he never sought revenge, but preached forgiveness against his captors - because it was for the greater good.

Now, pilgrims will trek a path to Mandela's home lands, where a nation's spiritual father rode bulls and played stick games, and where a boy dreamt of growing up to be a clerk, but instead embarked upon one of the most telling journeys of the modern world.

Here’s what you can expect with tomorrow’s Parramatta weather

As spring moves into summer what can locals expect tomorrow? We have the latest word from the Weather Bureau.

Here’s what you can expect with tomorrow’s Parramatta weather

As spring moves into summer what can locals expect tomorrow? We have the latest word from the Weather Bureau.