SEVENTY years ago, the final fight of World War II took place. You probably know it happened above Japan. But did you know it involved the British — and the famous Spitfire?

At 4am on August 15, 1945, pilots and aircrew of the Royal Navy’s Fleet Air Arm scrabbled onto HMS Indefatigable’s darkened deck off the coast of war-torn Japan. Assembled there were 18 of the most modern and lethal fighting machines in the world.

In the pre-dawn gloom on the last day of the war, one silhouette had been there the full six years since the first day — September 1, 1939: It was that of the Supermarine Spitfire.

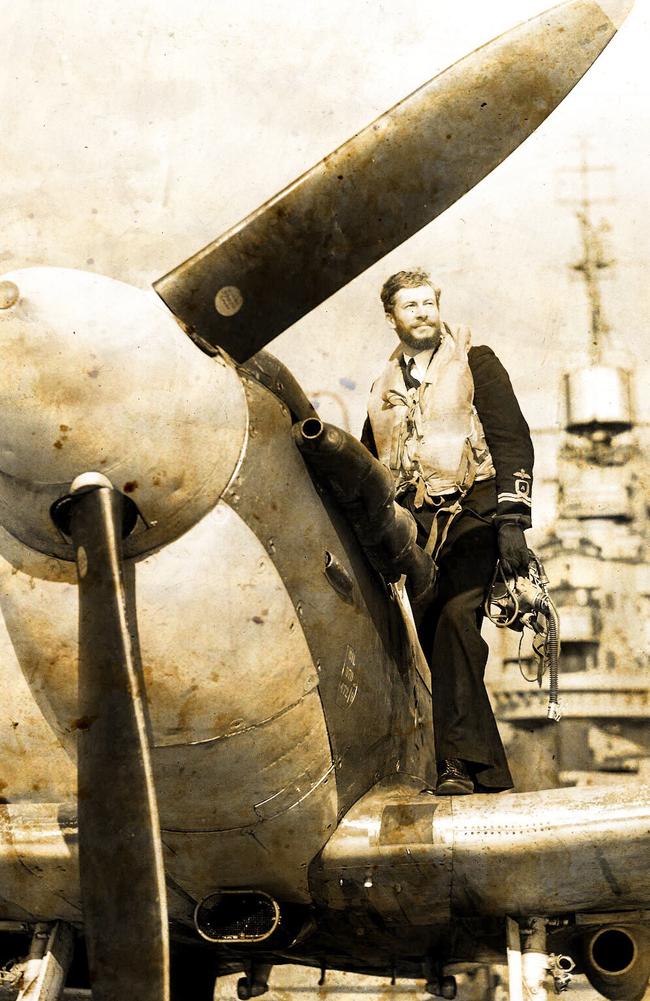

It wasn’t called a Spitfire anymore, though. It was a Seafire — a hastily adapted version of its famous Royal Air Force sibling, pressed into service aboard the Royal Navy’s aircraft carriers due to a desperate need for high-class fighter aircraft.

In truth the fighter was something of a compromise. Most of its pilots loved it. But many others loathed it. It lacked the strength and endurance to be a truly effective naval fighter. Once in the air, however, its foibles were immediately forgotten.

Commander R ‘Mike’ Crosley DSC RN, in his book They Gave Me a Seafire: “Once airborne, the Seafire responded with the sensitivity of a polo pony to nearly all our ignorant demands upon it. It behaved in its normal habitat with such unselfish grace and with such rapid response and power, that we knew we were being allowed to fly a thoroughbred. Once we were climbing away into the sky, all we had to do was keep our eyes open and the enemy could not touch us.”

It was just the landing bit that had everyone worried.

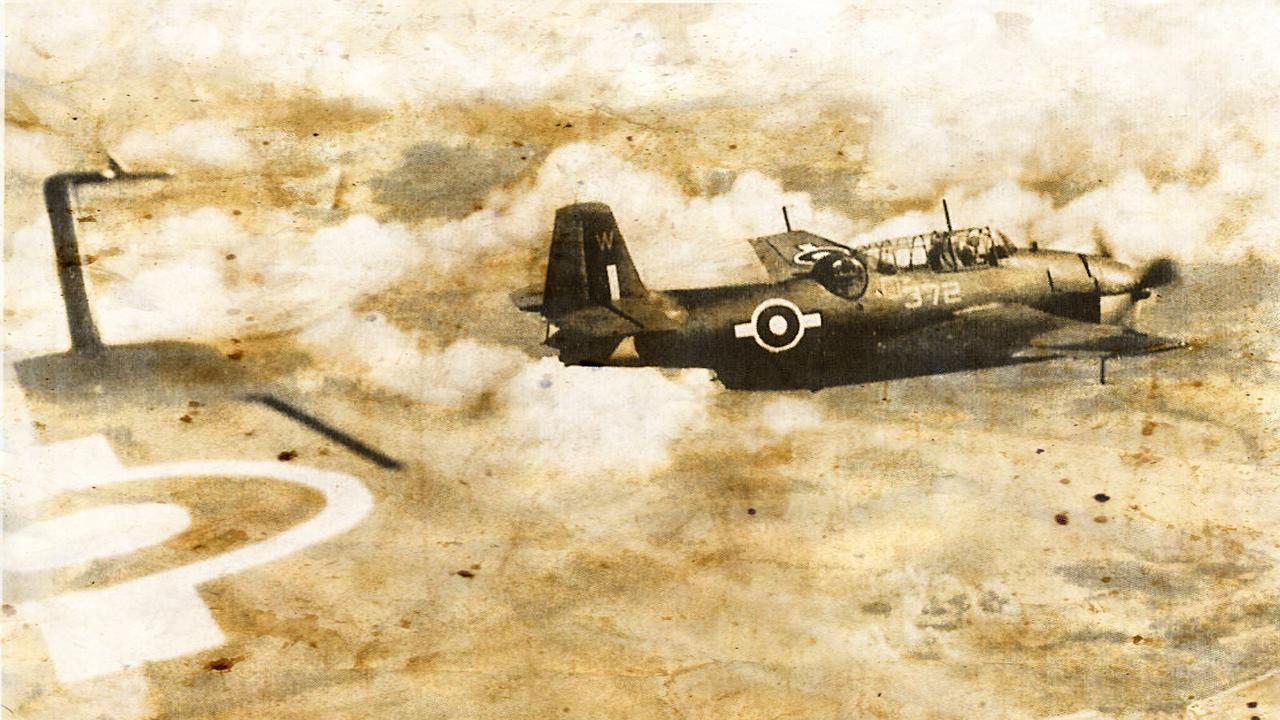

Eight Seafire interceptors of 887 and 894 Squadrons were arrayed on HMS Indefatigable’s deck that dark morning. So too were six Avenger bombers of 820 Squadron and four Firefly strike fighters of 1772 Squadron.

Their mission that day: To strike enemy airfields — but not to “unduly” risk life or limb.

Peace, after all, was likely just hours away.

Unfortunately, so too was a war crime.

Final fight

On Sunday, August 13, 1945, World War II was all but over. All knew it.

Word of Japan’s inquiries about surrender terms was well known.

The nation was on its knees. Nagasaki and Hiroshima had been blasted flat by an awful new weapon, the atomic bomb.

Tokyo was worse — charred to soot by firestorms that made those in Europe seem pale by comparison.

Now, the allies had agreed to Japan’s offer of surrender.

But Japan appeared wracked with indecision: Parliament was in deadlock. Final capitulation was yet to be formally declared.

HMS Indefatigable was only there due to pure bloody-mindedness on behalf of the British government. Many in the United States military wanted victory over Japan to be entirely their own doing.

Even since before the British Pacific Fleet had departed Sydney in February, the political machinations to sideline the force had been intense. But the US admirals on the front line were adamant: They wanted the experience and strength of the Royal Navy’s armoured carriers fighting alongside them.

But, now, victory was imminent. So excuses were made about fuel supplies and logistics — forcing much of the British Pacific Fleet to withdraw just as surrender was expected.

A token force clung on: The carrier HMS Indefatigable, the battleship King George V, two cruisers and their escorting destroyers.

Japan’s strange silence continued for two days.

So, before dawn on the morning of August 15, British and American pilots were once again ordered to take off from their dark, pitching flight decks with full loads of bombs to drop on the Japanese homeland. As encouragement.

Out of the sun

The decision to surrender was a hard one for proud Japanese nationals to swallow. But the atomic bombs — and the firestorms of Tokyo — had sapped the weakened nation’s will to fight on.

Long before August the Japanese military had virtually ceased to exist.

But remnants of Japan’s Imperial Air Force were determined to make a final stand.

They would use the last drops of their precious fuel and pull their few remaining fighters out from camouflaged hideaways for one last defiant fight.

The aircraft were the latest models of the infamous A6M “Zero” which had caused so much devastation during the opening year of the Pacific war. These were being flown by the 252nd Kokutai (squadron). Also active were a few of the newer J2M ‘Raiden’ fighters of the 302nd Kokutai.

At 5.45am, the British strike force crossed Tokyo Bay. The Avenger and Firefly strike aircraft prepared for their attack run on Kisarazu airfield.

Two Japanese Zeros were spotted below. The British strike commander hesitated: The Japanese had proven to be particularly devious. One such trick had been luring fighters away from vulnerable bombers by presenting what appeared to be easy targets.

A flight of 887 Squadron’s Seafires were in a high covering position. Several more Seafires of 894 Squadron were flying protectively above and among the heavily laden strike aircraft.

Moving either set of escorting fighters out of position prematurely would leave their charges vulnerable to attack.

His doubts proved well founded.

Shouts suddenly filled the airwaves: A dozen more Japanese fighters had now been spotted diving on the British from behind — their approach masked by the sun’s glare.

They were coming down in formations of four.

“It was the only day I saw a Japanese fighter,” Firefly observer Bennett is recorded as saying in the book The Kamikaze Hunters. “We were just about to go into the dive and I looked up and could see wings flashing and we could hear them saying, ‘look out’ over the radio.”

His strike fighter — in a steep dive to launch rockets at the airfield below — suddenly jerked. A defective windshield had fallen off. The crippled aircraft slunk away, unnoticed, at low level.

Dogfight

The fight was vicious.

The Seafires had reacted swiftly to the sighting report: Hauling their aircraft about to line up the Japanese fighters flashing past them in their gunsights.

One, however, remained on a straight and steady course. It was flown by 894 Squadron’s Sub Lieutenant Fred “Freddie” Hockley. He was in the lead of his formation: He did not see the Seafires peeling away around him.

Some accounts say his radio had failed. Others say he was slowing to release the heavy fuel tank slung beneath his aircraft.

Either way, the first Hockley knew of the approaching enemy was as cannon shells ripped through his Seafire’s thin skin from behind — shredding control lines and causing the massive Merlin engine to lose power.

Hockley retained enough control over his mortally wounded aircraft to roll it upside down, allowing him to unstrap his harness and “fall” to safety.

His parachute ballooned over Tokyo Bay.

By now the air battle was in full swing.

The lead element of Japanese fighters had blasted through the high-level Seafires and were charging towards the vulnerable Avengers and Fireflies below. Hockley’s flight — at a disadvantage as they were flying low and slow with the bombers — had nevertheless turned into the fight.

But now the second wave of Japanese fighters was also in sight. The high-cover Seafires approached in line-abreast.

Sub lieutenant Vic Lowden and a wingman of 887 Squadron had a Zero in their sights from 700 metres away. It was the second aircraft in the Japanese formation.

As the cannon shells from the two British aircraft struck, the Zero’s undercarriage fell away and the aircraft burst into flames. It tumbled towards the ground.

Aircraft tangled in a deadly dance to get into firing positions across the sky.

The Zero was nimbler: But the Seafire pilots knew that.

They also knew their famous aircraft was faster and could climb quicker.

They used this to their advantage.

Another Zero crossed into Lowden’s sights, this time only 180 metres away. He later wrote: “I closed to 100 yards at 11,000ft, kicking on the rudder to have a look at the markings, and then went back astern and fired two two-second bursts of machine gun fire — the cannon ammunition had already been exhausted. Following strikes all over the aircraft, the pilot bailed out. His fighter dived past him, smoking somewhat.”

Lowden, out of ammunition, was forced into a steep 425 knot (787km/h) dive to break away from the dogfight and return to the fleet.

Another 887 Squadron pilot, Sub lieutenant ‘Spud’ Murphy, had a lucky run. He had engaged in a “turning fight” with a pair of Zeroes — something he knew he wasn’t supposed to do. But his Seafire proved surprisingly capable of keeping the nimble ‘Zeroes’ in its gunsights.

He wrote: “Opened fire with my flight leader from the enemy’s port quarter. Saw strikes on fuselage of enemy, which was finished off by flight leader or No.3. Disengaged from above to attack another “Zeke” (Zero) to port and 500 ft below. Closed from above and astern, obtaining hists on belly and engine … but I was closing too fast and overshot. Pulled up nose to re-attack No. 2 and saw lone “Zeke” at same level doing a shallow turn to starboard. He evidently didn’t see me, and I held fire till some 100 yards away. Observed immediate strikes on cockpit and engine, which burst into flames.”

Down below, the US-built Avengers of the Fleet Air Arm strike were having a more difficult time.

The first wave of Japanese Zeros was among them: Their close escort of 894 Squadron’s Seafires doing the best they could to disrupt attacks. One, piloted by Sub Lieutenant Kay, set a Japanese fighter on fire and blew the tail off another in a remarkable 60 degree deflection shot.

Despite their efforts, some of the Zeros ignored the Seafires and opened fire on the lumbering Avengers.

One aircraft was seriously hit, suffering damage to its tailplane, elevator and starboard wing. The gunner, Petty Officer Airman A.A. Simpson, claimed to repeatedly hit and shoot down one of the assailants: A board of review did not confirm this “kill”, however.

The Avenger was struggling to remain airborne: Its observer electing to bailout over Tokyo Bay. The pilot and gunner remained with their aircraft until it could stay in the air no longer — ditching at sea alongside the fleet. Both were quickly rescued by an attendant destroyer.

In all seven Japanese fighters were claimed as victories by the British pilots. However, later assessment awarded only four “certain” kills with another four designated as “probable”.

It was by no means an entirely British affair: US navy fighter aircraft also reported clashing with the Japanese over Tokyo Bay that morning.

As the Fleet Air Arm aircraft turned for home, new orders flashed over the airwaves: Operations cancelled. Ceasefire to take effect 7am that morning.

Japan’s Emperor had finally formally surrendered. All that was needed now was for him to announce this final humiliation to his people.

Hostile territory

For Hockley, things could not get much worse.

Standing orders were to go as far out to sea as possible before ditching and bailing out. Submarines, destroyers and flying boats were on standby to snatch aircrew to safety.

The problem was the “as possible” part.

His crippled Seafire had plummeted over the coast, smashing into farmland near the town of Higashimura (now known as Chonan) on the Chiba Peninsula — east of the ruins of Tokyo — with a flash of fire and billow of smoke.

Hockley had drifted down nearby.

Residents quickly surrounded the downed pilot, who surrendered without resistance.

Resistance was futile.

The locals seemed reasonable enough: He shared with them the cigarettes and chocolate from his survival pack.

He was taken to the town’s school. It was being used as a staging post by the Japanese Army’s 426th Infantry Regiment.

Hockley was handed over to the soldiers there. He was blindfolded. Beaten.

He was dragged to a nearby farm house which had been commandeered by the Japanese regimental commander, Colonel Tamura.

The house-owner’s wife took pity on him. She gave Hockley a clean kimono to wear.

Hockley, in turn, showed her his necklace locket with a picture of his girlfriend inside.

It was noon on August 25 when Japan’s Emperor finally broke the silence.

His recorded voice was broadcast to the nation, reading the Imperial Rescript on the Termination of the War.

Hockley’s squadron mates back aboard HMS Indefatigable gathered on the vast flight deck to mark the historic moment: “Cease hostilities against Japan”.

The war was over.

But not for some.

War Crime

The commander of Hockley’s guards, Colonel Tamura, had also heard the broadcast. Uncertain of what this meant for his prisoner, he phoned divisional headquarters for advice.

Instead, he received an order: “Finish with him in the mountains tonight ... Do it in the dark so that no one can see it.”

About the same time, aboard HMS Indefatigable, those on the flight deck were watching the colourful hoisting of flags aboard the battleship HMS King George V to mark the momentous occasion. To those in the know, the flags read: “Cease hostilities against Japan”

It was now officially peacetime. Things could once again be done the traditional way.

Then a bomb exploded off the aircraft carrier’s stern. Then another.

A Japanese D4Y ‘Judy’ had slipped through the combined US and British air patrols and dropped two into the ocean alongside the Royal Navy carrier. But the aircraft soon joined them, “splashed” by US air patrol Corsairs.

Aboard the battleship the flags were quickly hauled down as another, more familiar, signal was rapidly raised: “Aircraft Warning Flash Red”. But no more attacks were to come.

Later that morning, American commander Admiral Bill Halsey, also in charge of the British fleet, broadcast a warning of further possible treachery: “It is likely that Kamikazes will attack the fleet as a final fling. Any ex-enemy aircraft attacking the fleet is to be shot down in a friendly manner.”

Back on mainland Japan, Sub Lieutenant Hockley was still restrained at the Japanese army camp. It had been his misfortune to parachute into a heavily fortified, secret facility. His captors already considered him to have seen too much.

Ten soldiers had been ordered to dig his grave nearby.

As dusk fell, Hockley was led out of his prison and into the countryside.

He was blindfolded.

His hands were tied.

He was made to stand before his grave.

Japanese Army Captain Masazo Fujino shot him twice in the chest from just one metre away.

Hockley did not fall.

Fujino fired again.

This time Hockley toppled backwards — into the grave.

Fujino later admitted to war crimes investigators: “He was still moving. He seemed to be in much pain, therefore I borrowed a sword …”

Three Japanese officers were tried as war criminals and found guilty of his murder. Colonel Tamura and Major Hirano, who ordered the execution, were hung. Captain Fujino, who carried out the order, was sentenced to 15 years in prison.

Sub Lieutenant Freddie Hockley, volunteer reserve, was the Royal Navy’s final casualty of the war.

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

Here’s what you can expect with today’s Parramatta weather

As winter sets in what can locals expect today? We have the latest word from the Weather Bureau.

Here’s what you can expect with tomorrow’s Parramatta weather

As winter sets in what can locals expect tomorrow? We have the latest word from the Weather Bureau.