30 years on from her disappearance, we look at the full case of Samantha Knight - from the inmate who heard her murderer’s confessions in jail, to the friends and family left behind.

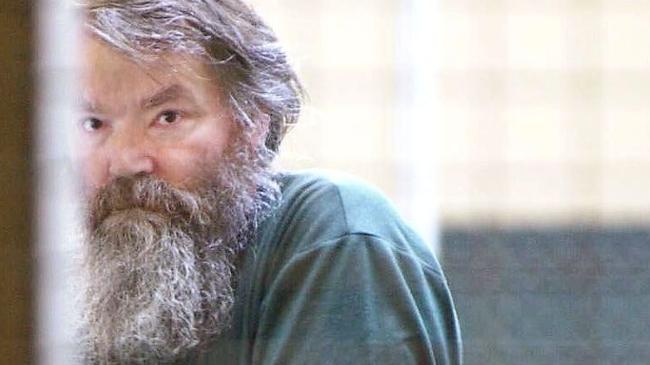

LOCKED in a protective prison wing with Michael Guider, the inmate did everything he could to block out the depraved stories from the ‘rock spider’.

Battling his own demons and struggling to come to grips with the realisation he was trapped in a cell thousands of kilometres from home, the Dutch national wanted nothing to do with the “sick puppy” and his evil ramblings.

But it was one of Guider’s stories that would help crack one of the most high profile missing persons cases in NSW history — the disappearance of Bondi schoolgirl Samantha Knight.

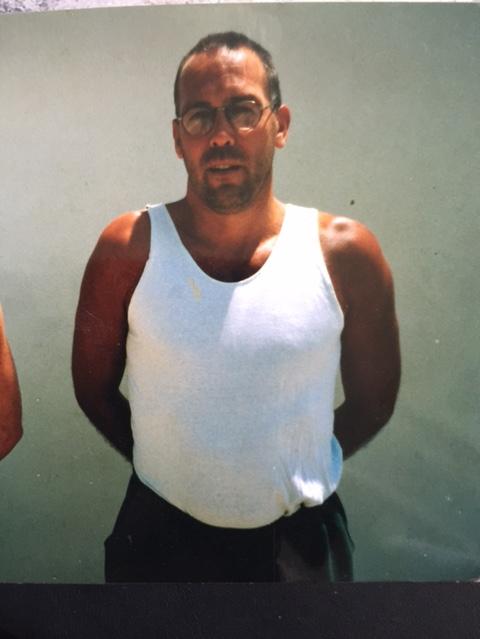

Previously known only as Witness O, the Daily Telegraph can now reveal that Frank Soonius, from Holland, was the prisoner who Guider confided in over his role in the death of nine-year-old Samantha.

Snatched from the streets near her Bondi home on August 19, 1986, Samantha’s disappearance and the mass search for her both captivated and terrified a nation.

Soonius was serving more than 10 years in Lithgow Jail in the 1990s for drug trafficking, having been caught when entering the country several years earlier, a crime he continues to deny.

Depressed and suicidal, Soonius had been placed in the protective wing for his own safety, while Guider was there to keep him away from other inmates who dished out prison justice to those who preyed on kids.

Guider would often talk about the young girls he had abused, but Soonius would block him out, not wanting to hear the boastings of a sick man.

“When I was in prison in 1998, I was so sick and all the things he was telling me I was always telling him to shut up,” Soonius told The Daily Telegraph from his home in the Netherlands.

“That’s why I never noticed he was telling me about more crimes and other things he had done.”

Soonius, now 58, then joined a prison bible group and when Guider asked if he could join, the foreign national and Christian took him along.

Most of the time they wake up (but) when I came home I went to the couch and she was cold. She was dead

“He really became interested in some parts of the bible I was reading about,” Soonius said.

After the classes, Guider began to become concerned with the horrible things he had done in the past and what that meant for his future and beyond.

“He said ‘Look Frank you will be forgiven when you walk away from here but I will always burn,” Soonius said, recounting one of their conversations.

“But I told him: ‘No, Michael because if you come clean and you do your 16 years in jail for the things you have done then you’ve also got a chance to start again.”

Soonius had no idea his fellow prisoner was involved in the death of Samantha Knight and thought Guider feeling remorse for the abuse he had inflicted on the children that led to his conviction.

But after some time, Guider came to him again and dropped the bombshell that would partly solve a mystery that had haunted the city for years.

“He said ‘I gave her something in the cola and some sleeping tablets and during what I was doing to her she became a little bit awake so I gave her another cola with a tablet in it and I went shopping,” Soonius recounted.

Guider continued to tell him: “Most of the time they wake up (but) when I came home I went to the couch and she was cold. She was dead.”

Samantha Knight’s body has never been found, but Soonius said Guider had told him in prison what he’d done with her remains after her death.

Two years after the she vanished another young girl is believed to have gone missing in the area. Not much is known about that case, but Soonius said Guider told him he was spooked by the police search and moved Samantha’s body from where he had buried it in Bondi.

“He was scared and before even the search started (for the second girl) he dug her up and put her in a container and made sure she went into where they burn all the garbage,” he said.

“Then he took her remains and made them so small and put them under all the garbage from the garden job he did and dumped it where the garbage goes.”

After he was charged with her murder — which would later be downgraded to manslaughter in a plea agreement — Guider told investigators he didn’t remember where he had buried Samantha.

But Soonius believes the killer was telling the truth when he recounted what he had done with her remains.

“That day for the first time I thought he was open and I thought he was telling the truth,” he said.

Soonius was released in August 2000 after giving investigators the evidence that would help be charged with murder and convince him to eventually plead guilty to manslaughter.

On returning to The Netherlands, he began the process of piecing back together his life, opening a tennis school and starting to write a book about his extraordinary time in Australia.

He also started the process of clearing his name of a crime he said he never committed - a fight he promises he will never give up on.

Instead of having to deal with the frantic pace of the city, Soonius bought a cabin in the woods outside of Amsterdam.

Coming to Australia was one of the worst decisions the Dutchman has made in his life, but he is comforted by the fact he was able to help close one of Sydney’s most horrible chapters.

When told of the possibility the killer could be released as early as February next year, Soonius said the thought terrified him.

“I’m scared, I’m really scared,” he said, obviously shaken at the prospect.

‘If you look into those eyes, they’re so horrible.’

“That scares the hell out of me. I hope they keep him under surveillance for 24 hours a day because he’s a really sick puppy, he really is.”

TIMELINE OF EVENTS

CHAPTER 2: ‘I WOULD PULL OVER AND CRY AFTER MEETING HIM IN PRISON’

IT was the phone call that changed the life of a Sydney school teacher forever and set her on a relentless path to bring a killer to justice.

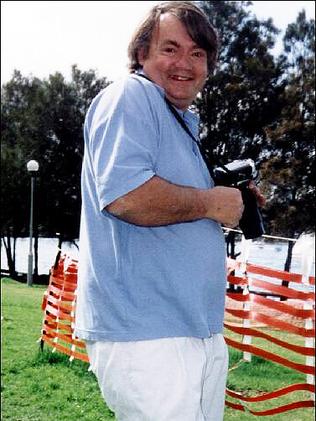

Mother of five Denis Hofman had just heard the shocking news that her friend Michael Guider had been arrested in March 1996 for the sexual abuse of children on Sydney’s Northern Beaches when her phone rang.

It was another acquaintance, a journalist who claimed Guider had confessed to her that he’d known nine-year-old Samantha Knight, missing for 10 years, and her mother Tess `quite well’.

Guider had confided in the woman that he often visited the site at Bondi where Samantha vanished and wanted to find the ‘truth’ about what happened to her.

The revelation immediately raised red flags for Hofman who begged her friend to go to the police.

But for reasons Ms Hofman still finds difficult to understand, her friend declined due to her friendship with Guider.

This sparked a near decade-long crusade to bring Guider to justice and one that would see her go head-to-head with some of the most senior police in NSW as she battled to convince them her former friend was a monster.

The pair had spent many days over the previous three years exploring bushland around Sydney and documenting significant Aboriginal heritage sites, especially in the city’s northwest.

Guider had snatched the nine-year-old off the streets near her Bondi home on August 19, 1986. He gave her a can of soft drink laced with drugs to render her unconscious while he took photographs of her. But when she began to wake he gave her another fatal dose.

He would eventually plead guilty to manslaughter and was jailed for 17 years.

Ms Hofman’s first step was to report the connection to police in Castle Hill. But when she wasn’t satisfied with her response she decided to take matters into her own hands.

Unbeknownst to her family, Hofman began visiting Guider in Lithgow Jail where he was serving a 16 year jail sentence for assaulting young girls.

Her aim was to subtly illicit a confession.

Such was his ability to manipulate people, Ms Hofman said she went away from those initial visits feeling like police may have the wrong man.

He would write to her in between visits and reminisce about their days in the bush.

“That’s all that keeps me going, locked in prison cells, the hope and faith that one day in the not too distant future I can go bush again with friends like you,” he wrote in one letter that Ms Hofman recounts in her book Forever Nine.

It soon became obvious that all this was part of his pattern of manipulation and deceit. He did consider Ms Hofman as a friend in the beginning, but he also understood those letters would be read by others.

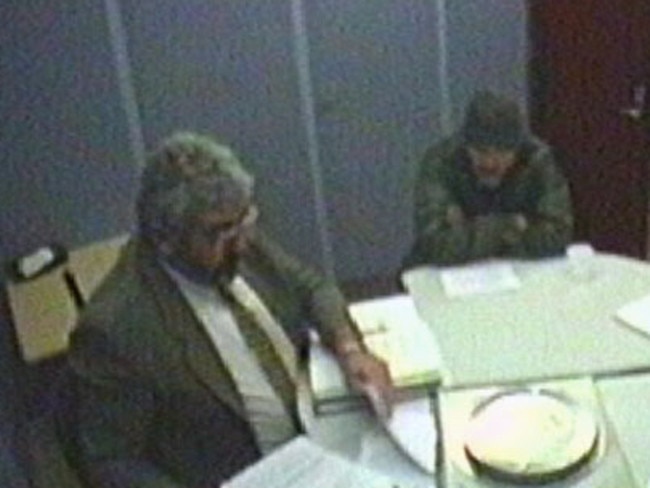

She kept visiting, more than a dozen times in total, but the man she describes as a ‘complete sociopath’ never gave anything away. He became aware of what she was trying uncover after a police officer mentioned her name while questioning him.

“I went to talk to Guider and I find out that two cops from Bondi had given him my name and the man who went along with me,” she told the Telegraph.

Ms Hofman claims investigators continued to brush her pleas aside. with one senior officers stating there was no Guider would be charged with Samantha’s disappearance.

“He said at that stage the Samantha Knight case and Guider was never going to go anywhere and we should just go on our way and forget about it,” she said.

It would take a further two years before police finally took Ms Hofman seriously.

Capitalising on the ongoing relationship she had formed with Guider, police secretly bugged the visitors room inside the Lithgow Jail and recorded the pair as they spoke.

But Ms Hofman also believes the police went a step further and bugged her own phones.

“We’d given my phone numbers - mobile and home - to Guider because at that stage we were encouraging him to ring me and he might say something on the phone and that’s all they were interested in,” she said.

Persistence eventually paid off. Further witnesses, including Guider’s own brother, came forward to testify allowing police to bring some closure to the 16-year mystery.

But Ms Hofman is convinced that her former friend is hiding more secrets and believes he should never be let out of prison.

During the investigation, hundreds of scrapbooks were found that had clippings from missing persons cases all across the country.

Ms Hofman has pleaded with police to examine these cases more closely as she believes Guider could hold the key to solving even more cases that have long gone cold.

Years spent chasing down a killer took its toll on the mother of five who wanted nothing more than to bring closure to a case that had haunted the city for so long.

“I would just pull over and cry after some of those meetings with him,” she said.

The endless brick walls she ran into with law enforcement also left a lasting impression on Ms Hofman.

“I’ve got no time for the police, they almost gave me a nervous breakdown, that’s for sure,” she said.

CHAPTER 3: THE LITTLE GIRL FROZEN IN TIME

“I WAS deeply affected and I still am.”

The loss of Tara Catsanis’ childhood friend Samantha Knight still haunts her 30 years on.

It’s not something she enjoys talking about. But she doesn’t want her friend forgotten either.

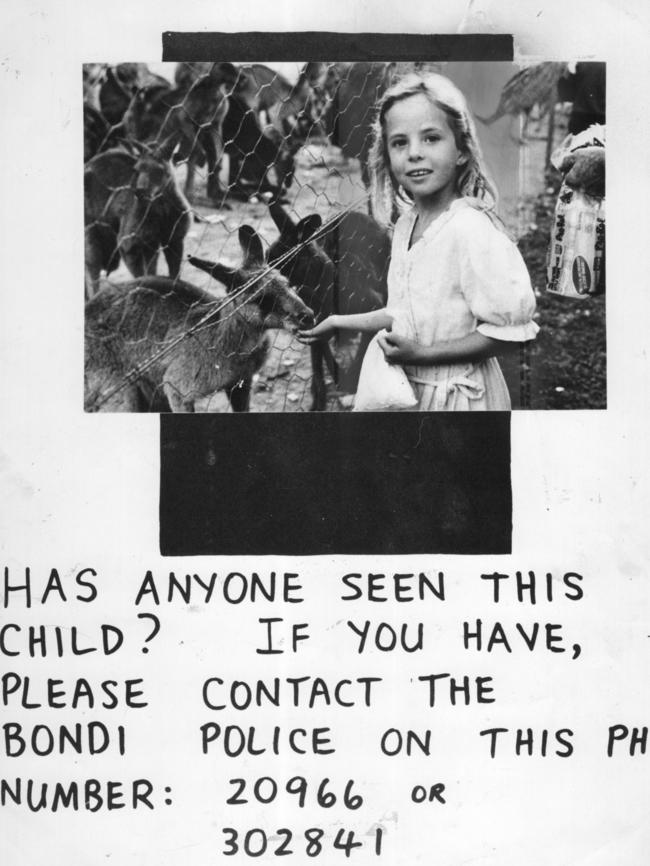

Samantha would have turned 39 this year but instead, she remains frozen in time, her nine-year-old face etched in the minds of Sydneysiders over a certain age — the little lost girl with the floppy hat and crooked smile.

When the Bondi schoolgirl vanished in 1986, it sent shock waves through Sydney and sparked one of the biggest police investigations for a missing person in NSW history.

At 4.30pm on Tuesday, August 19, 1986, she had simply walked out of her mother’s flat in Imperial Ave, Bondi, to go to the local shops. She never returned.

Samantha had been snatched by paedophile Michael Guider who gave her a fatal overdose of a sleeping drug in preparation of abusing her.

He would later plead guilty to manslaughter, despite the fact that he refused to tell the police where her body lay, and was sentenced to 17 years jail.

But without a proper burial, Ms Catsanis said the case wasn’t over for those who knew and loved Sam.

“I don’t have closure and won’t until she is put to rest the way she deserves,” she told the Telegraph.

“It changed me forever and I’m dreading the day they let him (Guider) out of prison.

“They should throw away the key. It’s not justice.”

A WAVE OF ANXIETY SWEEPS INTO BONDI

The abduction of Samantha profoundly affected her eastern suburbs community, not only because the family’s heartbreak played out so publicly, but because she could have been any kid.

Bondi was still a fairly close-knit community then, and although it had its share of transients, there wasn’t a local who wasn’t affected by her story.

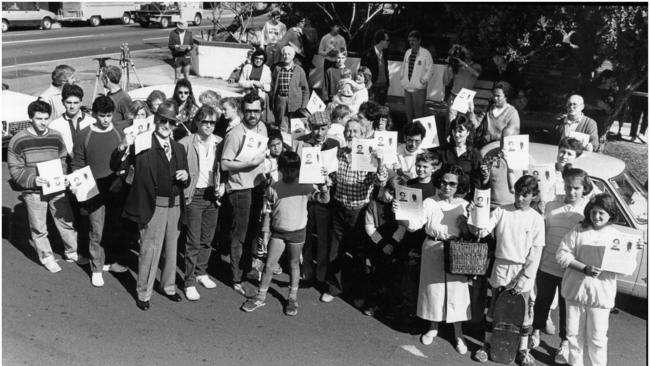

In the days and weeks after she went missing, the beachside suburb was swamped by police scouring the streets looking for signs of the missing girl.

Within 24-hours of her disappearance, it was the biggest story in town. Police enlisted the help of the media in an effort to throw up a clue. Parents Tess Knight and Peter O’Meagher gave interview after interview, hoping to jog someone’s memory.

Grandfather Bill Knight had thousands of posters distributed with his granddaughter’s face, and the little lost girl peered down at residents from every telegraph pole and bulletin board: “Have You Seen Samantha”, “Can You Help?”.

It was the days before social media, with only a handful of TV channels and radio stations, the wave of publicity didn’t rush up and fizzle out. It was relentless and inescapable.

A GHOST STORY OF STRANGER DANGER

False sightings and tips flooded in to police who pursued many avenues of inquiry but they ultimately failed to find Samantha — and the lack of progress wasn’t lost on local parents.

Many admitted feeling terrified for their children in the wake of the disappearance. The anxiety was tangible. Everyone knew it could have been their child.

“None of my kids will be going to the corner shop, or anywhere for that matter, that’s for sure,” one parent told a Daily Telegraph reporter days after the abduction.

“I’m using what happened to Samantha as an example to emphasise to my child how easily it could happen to them,” said another.

With school holidays approaching, the stranger danger message, with its flawed logic, was ramped up by police, who issued public warnings to children to tell parents where they were at all times. Small kids were told to learn their phone number and address. Safe Houses were pointed out.

By the end of the first week of her disappearance, three times the usual number of parents waited at the gate to pick up their kids at Bronte Public School, where Samantha had gone.

Talk revolved around precautions parents could take to protect their kids from strangers — the “sneaky, sly types” who snatched children out of the blue.

The overwhelming belief was that the greatest threat to their kids came from outsiders.

No one knew then that the man who snatched, abused and ultimately killed Samantha, wasn’t a stranger at all.

There had been a hidden connection between her and her abductor, Michael Guider, although it wouldn’t be revealed for a decade.

FEAR AND DISBELIEF HAUNT STUDENTS

While adults planned strategies to keep their kids safe, Samantha’s friends were struggling to make sense of her absence.

On their way to school, many would pass the life-size mannequin of the missing girl, placed by police near the corner of Imperial Ave and Bondi Rd, where she was last seen.

One student, 11-year-old Carolyn Sanasi, who regularly walked part way home with Samantha spoke of her own fear: “I’m scared now and I’ve cried about Samantha a lot since she went missing.”

Meanwhile, Ms Catsanis, one of Sam’s closest friends, had nightmares and was riddled with irrational guilt.

“For her mum to ring me first that day and ask if she was there, I felt guilt,” she said.

“I felt like she should have been at my house, and somehow it was my fault. I know it’s silly, but as a kid you don’t understand.’’

Inside the walls of her school, teachers tried to support Samantha’s classmates through their uncertainty and sadness.

“In the days that followed, it was very hard for anyone to think of anything else,” then principal Peter McCallum later told the Telegraph.

“Police were trying to retrace Samantha’s last movements — and because she was a child, that meant the search had to be conducted among children.

“Sometimes I would make the first contact (with families) because people were almost traumatised when the police identified themselves as being homicide branch.

“It was hard just to concentrate on ordinary school routine. There was a very hollow feeling.’’

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

Deer in the headlights or really good cop? Who is Karen Webb

Karen Webb has become our most divisive public servant since she was appointed NSW’s first female Police Commissioner in 2021. With her exit from the job looming, here’s the inside story of her time in the role.

Everyday heroes: Regional NSW residents land Oz Day honours

Not all heroes wear capes – and it couldn’t be more true for these everyday champions from Regional New South Wales who have been honoured this Australia Day. See the full list.