WE are just above the Lebanese yard, on a walkway between the guard towers, when an apple, half-eaten, suddenly rushes past photographer Sam Ruttyn’s head.

Below us are 20 inmates roaring with jubilation and shouts of “Allahu Akbar”. They have a stockpile of apples that they’re launching missile-like toward us. One makes a high-arc over our heads. Another descends beyond the prison fence line, proving distance is no obstacle. These are long-range apples, it seems, heatseekers and sidewinders.

There’s not much we can do to stop all this; the walkway is narrow and there’s nowhere to go except the next guard tower. We know it, and they know it. A third apple lobs just as the riot squad arrives and against we’re forced to duck like a couple of idiots. When we finally reach the watchtower I ask the officer escorting us, only half-jokingly, why no one opened fire on the prisoners.

To be clear, those apples were meant for me, not for Sam: apparently I’d offended one of the inmates, an Islamic State supporter doing 18 years for a murder at Fairfield. For the record, though: he started it.

“Hey Yoni!” he shouted a few moments earlier, a big smile on his face. “Death to Jews! Death to America!”

So I smiled back and gave him the finger, double-barrelled, both hands. I’d had enough of being heckled. Barely an hour had passed since some Islanders in ‘Four Yard’ gave me stick about my skinny jeans.

“Oi bro,” one of them shouted through the hurricane fencing. “How do you fit into those?”

“Yeah, bro, those are girls’ jeans,” said another the size of an Easter Island statue. “They’re like stockings.”

All part of the experience, an official later tells me. Heckles and apple throwing, urine, faeces, spitting, boiling water — these are just a slice of what prison officers navigates every day, which is what’s brought us to Goulburn Correctional Centre in the first place.

We were invited by Peter Severin, the Commissioner of Corrective Services, ahead of the first annual Corrections Day to be held this Friday, an event that will honour the 7,000 prison officers, psychologists, counsellors, and numerous other correctional staff working across the state’s 35 prisons.

Goulburn has always been home to the state’s worst offenders: lifers like the Murphy brothers, whose slaying of Anita Cobby sickened the community; Ivan Milat, the backpacker murderer; Phuong Ngo, who orchestrated the assassination of Cabramatta MP John Newman; and Roger Dean, the mass killer who burnt down a nursing home, killing 11 people.

It’s a 19th century prison. Sandstone and red-brick. Concrete and steel. It’s brutal in summer and just freezing in winter. There are 558 inmates plus another 44 housed in the ultra-secure ‘Supermax’, better known as the High Risk Management Correctional Centre.

Our tour is an all-access showcase that few journalists or photographers have been granted in recent times. (The only condition placed upon us while we’re here is that we don’t identify the inmates we encounter, mainly out of respect to their victims.)

Roughly half of the inmates at Goulburn are housed in some form of protection or segregation, which is one reason why murders don’t happen anymore.

Years ago murders were routine, which is how the yards came to be dubbed the “Killing Fields”. Today, the murders have ceased, but assaults still happen and officers are constantly playing a shuffling game to ensure prisoners with beef are kept away from each other.

There’s a YouTube video of one former Goulburn resident, Rodney “Goldie” Atkinson, pummelling a fellow prisoner, a protected inmate in a caged yard, because the prisoner had murdered an elderly woman.

Officers are constantly playing a shuffling game to keep inmates with beef away from each other. But the big reason why murders don’t happen anymore is because of “racial clustering”, a policy that saw inmates segregated by ethnicity. Today there’s an Aboriginal yard, a Lebanese yard, an Aussie-Asian yard, and an Aussie-Islander yard. Goulburn is the only prison where this policy is enforced.

Far and away the most surreal stop on this tour is a building called Multi-Purpose Unit (MPU), a 57-bed protection facility where some intensely horrible people are kept behind 18-foot walls and lots of razor wire. These are major-league criminals.

It’s here where we meet a rapist with a household name doing 32 years for his crimes against women. He’s fat now, much paunchier since his mugshot was first taken. “Yeah, I’m good,” he concedes as we shoot the breeze. He invites me to come back for a one-on-one visit some day. “I’ll give you an exclusive story,” he says, “a real one; but only you, no one else from The Telegraph”.

A few metres away is a man serving three life sentences for slaughtering three relatives to access his inheritance. He looks nothing like the weedy kid the world remembers. Today he’s jacked with muscles, spends most of his time training, and remains pathologically determined to prove his innocence. He allows us to look around his cell while he waits for his rice cooker to boil.

Guiding us through all this is Senior Correctional Officer Barry Butterfield, an affable and instantly likeable 30-year veteran of the prison system who knows everyone here and works in the jail’s Reception Centre, the first stop for newly arriving inmates.

There, they get inducted into prison life: their mugshot is taken, they’re given a Master Index Number (MIN), an ID card, a meat pie if they’re hungry, a cup, a plate, and a ‘showbag’ of essentials — prison greens, a towel, shoes, a toothbrush, and a razor blade, which is sometimes combined the toothbrush to make a rudimentary shiv.

Weapons like these are routinely found here: just a few hours before we arrived at the jail a blade was pulled from an inmate during a strip search; when questioned, the inmate said it was to protect himself, not to assault staff, but the excuse was treated cautiously.

“These people can just turn on a dime,” Butterfield says, as we make our way towards X Wing, a medium security centre that’s tree-lined and shaped like the bottom half of the letter ‘H’.

It’s one of six units at Goulburn, but it’s located on the jail’s outer periphery, away from the main population.

It looks like a pretty typical government housing block; the only giveaway that it’s a jail is the mesh grating across each window, which some inmates use to hang their wet socks and underwear.

Inside, the place has the atmosphere of a boys’ home. Inmates move around freely and crack jokes with the officers. The median age is about 26. Most spend their days working in the prison workshops or cleaning up graffiti in the community.

At night they’re locked down in their cells, which have an inventory consisting roughly of a: calendar, crucifix, shoes (several pairs), cards, books, laundry sacks, numerous spray bottles with brightly-coloured detergent inside, hand sanitiser, plastic food containers, a mirror, safety razors, and a small reading light attached to one of those flexible wands.

Posters are banned, but photos are fine, and there are plenty of racy and motivational pictures of women posing in a kind of this-is-what’s-waiting-for-you-when-you-come-home way.

Fighting is rare in X Wing, but Butterfield says every prison officer at any jail will always be alive to the low-humming vibe of impending threat. Not too long ago, one of his colleagues in another part of the jail had his hand carved open while passing a meal tray to an inmate through a slot in his cell door, one of 240 attacks on officers recorded during the 2015/2016 financial year. Nine of those attacks happened at Goulburn.

What’s less common, however, are assaults on female officers, which are apparently are frowned upon.

“Most inmates still have a little bit of value,” says Larry Bolger, the Governor here. “If you put a male [officer] on his arse you’re seen as a bit of a hero, but if you smack a female officer it’s a dog act.”

Ironically it’s the lifers, Bolger says, who are less likely to start trouble. He’s been in charge here nearly four years and says it’s the ones who “blow in” for a few months and don’t really care who are generally problematic. “If you know you’re going to be here 20 years you’ve got to make the best of that,” he explains.

Most inmates do their time by working for the commercial arm of the prison system known as Corrective Services Industries (CSI), which pays between $20 to $55 a week. At John Moroney Correctional Centre the inmates make breakfast packs for jails across the state; at St Helliers in the Hunter Valley they grow vegetables which end up as inmate rations; at Glen Innes there’s a sawmill producing timber products for sale.

At Goulburn it’s a warehouse of factory floors where prison greens and furniture are made. There’s also a laundry. In the room known as ‘Textiles 1’ we find several dozen sex offenders sitting at banks of sewing machines and making jumpers, shorts, T-shirts, bras, and tracksuit pants for prisoners statewide. A few guys have a card game going as they wait for more fabric to work with. There’s a radio on. Nearby is a room filled with computerised machinery where desks, drawer units and kitchen cabinets are made for the Department. About 40 prisoners are entrusted to do this work using chisels, drills, and other tools that could potentially be diverted to make pretty serious weaponry.

“You can’t really trust any of them,” says Butterfield, “but their work ethic is quite good. Work is important to a lot of them because it breaks their time up a little bit.”

The most impressive weapon seizures are on proud display near the Governor’s office, a glass cabinet of shivs and knuckledusters, some of which look too well-crafted to have been fashioned by hand alone. They’re fascinating to look at, but also emblematic of prisoner resourcefulness; this is, after all, the prison where an inmate scaled a wall and briefly escaped in 2015 using nothing but bedsheets, a mop handle, and a pillow to avoid cutting himself on the razor wire.

The angles for mischief are everywhere: in the ‘Carp Shop’ where the furniture gets made, Butterfield watches an Asian inmate rubbing a rolling pin up and down his legs. The prisoner smiles as we try to figure out what he’s doing. “Massage,” he tells Butterfield, which sounds harmless enough, a bit of relief for a full day on his feet. Butterfield thinks he’s just making his legs fight-ready by “toughening up his shins”.

As we’re led inside the prison laundry, a small room lined with industrial-strength washers and dryers, we lock eyes with some very recognisable faces. There’s an inmate wearing a crucifix who happens to be one of Australia’s worst mass killers, a man who deliberately burnt down a building, killing several people. There’s a notorious killer doing life for the murder of a drug dealer. They now spend their days washing blankets and linen for fellow inmates at Goulburn and Berrima prisons.

Seeing these people is strange for obvious reasons, but it’s made stranger by the misplaced familiarity, the do-we-know-each-the sensation that takes hold whenever you see a high-profile person in the flesh. Except here, that sensation gives way to a dark and unsettling feeling, sometimes even a jolt through the body from shock when the person’s heinousness is realised.

This is celebrity spotting on a really macabre level, and it’s in these moments when the world of the prison officer becomes clear: it’s occluded and unsung, walled off from society. We applaud judges who hand down hard sentences, but they will never have to live with these people. Like the rest of the community, they will never have to witness or manage the slow decay of a person doing life in a cell.

“The staff work in a difficult environment,” says Vicki Walcott, one of the counsellors assisting inmates housed in Supermax. “They carry issues that worry them.”

Compensation claims are high among prison officers, according to Safe Work Australia figures, up there with police and paramedics, but lower than train drivers who often witness people committing suicide. They have an ally in the NSW Custodial Inspector. His recent report — The Invisibility of Correctional Officer Work — concluded that prison officers were judged unfairly by the media, did incredibly tough work, and were assessed according to bureaucratic metrics like assaults on staff, assaults in general, escapes, etc. — all of which comprise a fraction of their day-to-day reality.

“There’s a lot more to it than a bloke who comes to work and picks up a set of scissor keys,” says Butterfield. “You wear a lot of different hats, you know? You’re a welfare officer, a psychologist. Sometimes your job is to talk to people and stop them doing silly things. You’re someone who has to care for them when they’re banging their head up against the wall.” Then he rattles off a string of recent incidents. “Just the other day we had a bloke set fire to his cell and refuse to come out, so we had to go in and get him. There was smoke everywhere and we didn’t know if he had a weapon or not. We got him in the end, but you don’t hear about that.”

Instances like these happen from time to time, but in the event of a major incident there’s a dedicated riot squad — the Immediate Action Team — which can be anywhere in the prison complex within a flat 30 seconds. Their headquarters is a corridor of decommissioned cells set up for cell-entry drills and other training scenarios. Instead of firearms, they carry gas masks, batons, and work with high-powered ‘chemical munitions’ that come in varying grades of intensity — from a thick, disorientating smoke, to a membrane nuking compound that can put a man on the ground almost instantly.

“You feel like you’re choking up,” says an inmate who’s experienced the effects of this gas first hand, a killer serving life, a man whose crimes have been portrayed in an Underbelly series. “Your eyes are watering, your face is on fire, it affects your breathing — you go into panic mode.”

These measures are mostly saved for riot-style scenarios, which, when they happen, tend to break out in Goulburn’s yards, 12 cake-slice enclosures abutting each other in an arrangement known as ‘the Circle’. Cutting through this ‘Circle’ is a laneway dubbed the ‘Backline’ where the former Hey Dad! star, Robert Hughes, was famously pelted with urine and faeces on his arrival at Goulburn. Mesh fencing has since been added to the Backline to prevent a repeat of the incident.

But it does nothing to stop the hollering as we walk through the Backline towards the MPU past dozens of inmates shouting over each other. A Koori prisoner pulls off his shirt at the gate to his yard and says: “This is what a real n..... looks like.” Some ham it up for a group shots. We see a well-known inmate in the Aussie-Asian yard giving us the finger, subtly, as he considers a chess move.

The MPU is Goulburn’s fulltime protection and segregation unit, a dizzying place of notorious and psychopathic personalities who are housed on various decks. For some it’s been many years since they’ve been seen by civilian eyes. We see a man in one section stirring a cup of coffee, a double-murderer with a large build who decapitated his first victim and tortured his second. For his size, he seems a little nervous, almost timid.

“Behaving yourself?” Butterfield says to him.

“Yeah chief,” he says shakily. “I’ve got a job now, which is good.”

It’s a pretty social atmosphere in the ‘A’ deck and there’s patriotic feel to the place. The walls are decorated with NRL team decals and Australian flags. Two inmates are doing push-ups in front of a Boxing Kangaroo poster. A bikie holding a hand mirror is getting a haircut. The only person excluded from all this is shouting at us through the small Perspex window from his cell; the shouts are muffled, and there’s a tattoo covering half his face, from his hairline to his chin. There are numerous signs posted around his door saying ‘DO NOT LET OUT’.

“He’s the one Dutton’s trying to have deported,” a fellow prisoner reveals, referring to the Immigration Minister, Peter Dutton, who’s been deporting violent people on character grounds.

The sweeper here is serial killer doing four life sentences, two being for the murders of Victorian police officers. He’s a pallid and ghoulish-looking man who says “sorry” every time he ducks past us in the hallway, which is where we’re standing when an officer calls out “inmate coming through” as he escorts a jump-suited inmate towards an interview room. The prisoner is gaunt and catatonic-looking but instantly recognisable — he was once australia’s most wanted fugitive.

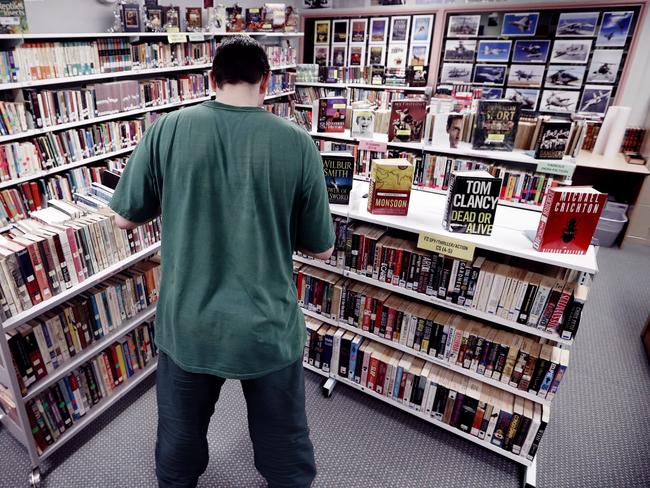

But it’s the privileges here that both surprise and catch us off guard. I came here expecting lair-like conditions, but on ‘B’ deck we see inmates having a sausage sizzle. On ‘A’ deck there’s a ping pong table. In the library are enough books — Tom Clancy to Haruki Murakami — to keep a man busy for three lifetimes.

And while these privileges might seem out of place in a maximum-security prison, the research shows they make a big difference to maintaining order. Lots of prisons use similar tactics: the informant wing of Long Bay jail was recently dubbed ‘Club Med Malabar’ during a gangland trial because some inmates were being fed steaks and ice cream.

Society expects its prisons to be miserable places, but studies show harder jails only create harder inmates who are more likely to assault staff, commit misconduct, and reoffend on release. As it stands, NSW already has some of the harshest prison conditions in the country: prisoners are locked down for more hours in their cells than in any other state, and we spend less dollars per inmate — $188.82, per day — compared with the national average of $221.92.

There’s only one lingering question as we part ways with Barry, and that’s why anyone would willingly sign up for this work, a job that even on a great day means interacting with society’s despicable few. Unlike police officers or nurses, there’s no obvious reward for doing it. So why?

“The people,” he says. “They go into work every day not knowing what might come at them. And what we do isn’t heroic, but we do our job exceptionally well.”

- Yoni Bashan

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

Inside the call that changed Hadley’s tune on Webb

Karen Webb has become our most divisive public servant since appointed NSW’s first female Police Commissioner in 2021. Supporters say she has been unfairly maligned in “misogynistic” attacks. Detractors say she’s not a natural leader. Here’s the inside story of her time as “top cop”.

Everyday heroes: Regional NSW residents land Oz Day honours

Not all heroes wear capes – and it couldn’t be more true for these everyday champions from Regional New South Wales who have been honoured this Australia Day. See the full list.