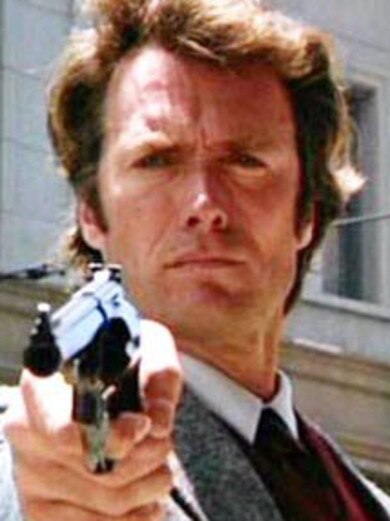

PART ONE: It was a baptism of fire. Roger Rogerson rode shotgun with the toughest and dirtiest at a time when Sydney was plagued by as many bank robberies as New York. It was the perfect time to be a cop.

He was armed and soon to be very dangerous.

Born in Sydney’s Crown Street hospital on January 3 in 1941, Roger Caleb Rogerson’s father Owen was a skilled boilermaker who worked on the construction of the Sydney Harbour Bridge and later at the Sydney Shipyards during the war.

A migrant from Hull in England, Owen met and married a 19-year-old dressmaker called Mabel Boxley from Bondi in 1939.

Despite Rogerson spending most of his police career dealing with inner city crime, he always lived in the Bankstown region.

He attended Homebush Boys High. And when he married, Rogerson moved to Gleeson Avenue in the neighbouring suburb of Condell Park. He was still living there with his second wife, Anne Melocco, when he was arrested for the 2014 murder of Jamie Gao.

His father was a committed Communist who didn’t like coppers’ and his mother was a regular churchgoer. She would drag her unenthusiastic son to mass every week, where he played the organ. His family and friends were surprised he wanted to join the force, but the idea seems to have germinated in his early teens after a cousin signed up.

In 1958, aged 17, Rogerson applied for a position as a NSW police cadet. The only real requirement was a minimum height of 174cm, not having a criminal record and being of “good character”. As a potential police officer Rogerson excelled.

As luck would have it — and Rogerson seemed to have a lot in the early part of his career — his first fulltime position at a police station was in Bankstown. He spent the next two years as a uniform officer in the area learning the ropes, locking up petty crooks and doing his share of the nightshift. He had the jump on his peers because he knew most of the “ratbags” from his childhood.

“No one could say they had finished a shift without a couple of good arrests,” he once said about life as a Bankstown copper.

“As soon as you left and got in a police car you had work to do — and it normally ended up in an arrest somewhere.”

But the drudgery of uniform police work wasn’t for the ambitious Rogerson. He had his sights set on being a detective.

In early 1962 he got his wish.

At the earliest possible time allowed, which was three years, Rogerson was out of the blue uniform and into the plain clothes of a detective. Within months he was attached to the famous 21 Division. Known as a “Flying Squad’’, it was a law unto itself. The division existed to target any crime the government or the police bosses wanted cleaned up. It was mainly made up of ex-soldiers suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder.

For a newbie, it was a baptism of fire. Rogerson was thrown into a squad with some of the toughest and dirtiest cops in the city. On the surface Sydney was a clean town, but in the backstreets of Paddington, Surry Hills and Kings Cross it was littered with sly grog shops, illegal casinos and brothels.

Rogerson spent two years with the 21 Division before moving on to the Special Crime Squad, stationed in the heart of the city where he worked on everything from petty crime to murders.

In 1964, he married a local girl called Joy, who he had met at church. The couple would have two children before they split in the 80s. In the late 60s and 70s there was nothing to suggest Rogerson was anything more than a hard cop who took delight in locking up crooks. There was no hint of the corruption and criminality to come.

Many of his colleagues believe he was “relatively straight’’ in those early years. Yet, others had doubts. Coincidence seemed to follow Rogerson. In 1963, as a 21-year-old detective, Rogerson was ordered to help local police and Homicide detectives investigate the murder of a would-be standover man called Robert James “Pretty Boy’’ Walker. He was machine gunned to death as he walked down the street in Randwick.

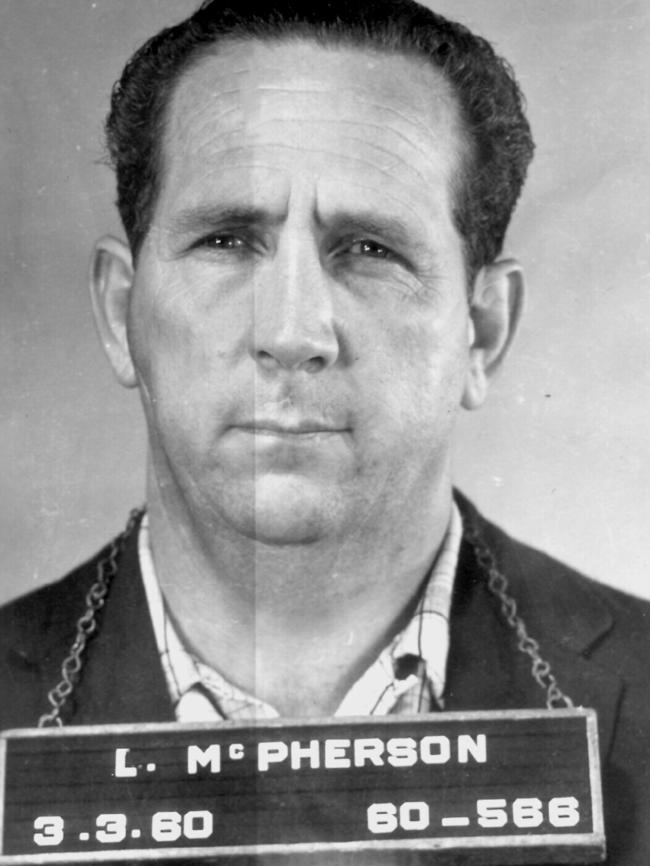

Rogerson somehow found the getaway car one week later. He says he did it by knocking on doors. But the prime suspect at the time was Lennie McPherson, soon to become the legendary “Mr Big” of Sydney.

No one was ever charged with the murder despite it becoming common knowledge Walker was killed for bashing one of McPherson’s minders, Stan “The Man’’ Smith. Rogerson would later admit that McPherson was one of his best informants. The two would often meet in “little joints” along Kings Cross at about 3am to trade secrets.

In 1970, Rogerson and his partner Noel Morey were asked to help work on the biggest robbery in Australian history at the time when Mayne Nickless stole from an armoured van at gunpoint in Guildford. The robbery was planned and carried out by three criminals from Melbourne with connections to the notorious Painters and Dockers gang.

During the investigation Rogerson would frequently go to Melbourne, using the case to come into contact with some of the city’s heaviest crooks. He also worked closely with Sydney’s infamous Toe Cutters gang, whose name stems from their go-to form of torture — cutting off a person’s toes one-by-one.

As a detective Rogerson had an impressive arrest record and worked on a number of high-profile cases.

He often talked about the murder of a 14-year-old schoolgirl Maureen Bradley, who was abducted as she walked home from school near Mt Ku-ring-gai in 1971. Her body was later found mutilated with a beer bottle at Brooklyn.

Rogerson and his partner were assigned the case. He has told the story many times of how he and other detectives worked from 5am until midnight hunting down her killer.

Rogerson also helped Brisbane detectives in the Whisky Au Go Go fire, where 15 people burnt to death. His work on the case was heavily influenced by information gleaned from McPherson.

After nearly a decade as a plain clothes detective, mainly working on homicides in and around Sydney, Rogerson was transferred to the Armed Hold-Up Squad.

It was affectionately called “The Stick-Ups’’.

One of his first arrests in the elite squad was of a young Melbourne armed robber called Christopher Dale Flannery, who came to Sydney while on the run.

In another one of those coincidences, it was Flannery who would later be named as the gunman behind the attempted murder of star NSW police officer Mick Drury. Rogerson would be charged over the shooting, but acquitted.

The Armed Hold-Up Squad officers were all highly trained in special weapons and considered absolutely fearless. Their best friends were their Remington 870 12-gauge shotguns and their sworn enemies were the many crooks who specialised in bank hold-ups and armoured vehicles robberies, which occurred daily in the 70s.

“It was dangerous work and Roger thrived on it,’’ one of his colleagues in the squad, Brian Harding, told The Daily Telegraph.

“Around that time we had as many bank robberies as New York and one year we had more.’’

From 1976-85, nine armed robbers were shot dead (two by Rogerson — and he was present at least one other, Gordon Thomas at Rose Bay). Four police officers from the squad were also shot, but survived.

The fit was right for Rogerson. He loved the adrenaline. He once described it as the perfect time to be a cop. There was no fancy technology like today and you didn’t “mollycoddle” the “jerks” you were after. Your weapons were “fast cars”, “shotguns in the trunk” and your wits.

“Cops are weak as water these days,” Rogerson would later say.

It was while in the Armed Hold-Up Squad that Rogerson received his highest accolade — the Peter Mitchell Award for locking up three desperate escapees and armed robbers who had shot and killed a young bottle shop manager. As Rogerson shot and arrested his way to glory he came across an up-and-coming career criminal called Arthur “Neddy” Smith.

Then the body count started to grow.

Here’s what you can expect with tomorrow’s Parramatta weather

As we move into summer what can locals expect tomorrow? We have the latest word from the Weather Bureau.

Here’s what you can expect with tomorrow’s Parramatta weather

As we move into summer what can locals expect tomorrow? We have the latest word from the Weather Bureau.