Yoni Bashan takes readers on a gripping journey with the Middle Eastern Organised Crime Squad in his book The Squad, revealing the inside story of the dangerous operations to combat organised crime families. In this extract a rocket launcher is discovered in Sydney.

Bankstown, Saturday, 30 September 2006

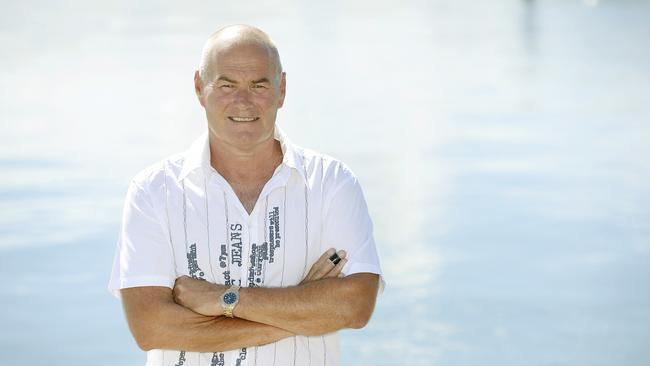

KEN ‘Slasher’ McKay, Commander of MEOCS, stepped out of his car onto Stacey Street and walked towards the two shady-looking men standing in a driveway across the road.

If McKay was nervous, he didn’t show it. There was a loaded gun down the back of his footy shorts.

In his shirt pocket was a mobile phone, its line open for detectives nearby, ready to broadcast any signs of distress.

It wasn’t the world’s most sophisticated body wire, McKay thought, but it would have to do. Flanking him as he crossed the street was Mark Wakeham, a gifted 20-something-year-old detective and the architect of this gathering. Wakeham was very familiar with the men they were meeting.

He’d studied them, knew the dangers; there was no way he was letting McKay meet them on his own. They were leaning against a car and popped the boot as McKay and Wakeham got closer. Inside was a torn-up garbage bag with an olive-coloured tube sitting on top of it.

The tube was about one metre long with capped covers on both ends and had a shoulder strap that hung loose. On the side were helpful, illustrated, step-by-step instructions: pull pin, remove rear cover, extend, release safety, aim and fire. McKay looked at the tube then back at the men.

‘Is that it?’ he asked.

They said nothing, just nodded. It was a rocket launcher, one of an untold number that had been stolen from the army and, as the lore suggested, sold into the underworld. It was a one-shot device, light enough to hold up with one hand and capable of causing heavy casualties in a civilian setting.

In policing terms, this was the Holy Grail, El Dorado and the lost city of Atlantis rolled into one: after years of conjecture and fruitless searching, McKay was finally looking at something the Australian Defence Force (ADF) insisted had never gone missing from its stockpiles, and from what he knew there were others still out there.

Military brass had been adamant that all their rocket launchers were accounted for – either secured in their armouries or destroyed via decommissioning. The notion that even one device, let alone several, had made it into the hands of a criminal was scandalous. McKay probably should have called the Bomb Squad on the way out to Stacey Street, but he didn’t. Too much fuss, he thought.

Protocol would have called for the street to be shut down and homes to be evacuated, but McKay, an old-school type, couldn’t be bothered. He didn’t have time to organise all those ‘bells and whistles’, as he called them, and it wasn’t his style anyway. He was a larrikin, a swashbuckler, a throwback to a time when the rules were bent just enough to get the job done, a larger-than-life character who could have stepped right off the script of a 1970s cop show, the ones that open with a montage.

Detectives still trade Ken McKay stories, passing them around like football cards, each time embellishing them just a little more in his favour.

In this one he’s chucking a live rocket launcher into the boot of his car, ignoring every workplace safety protocol imaginable; in another one he’s being demoted to the Property Crime Squad as punishment for telling his boss – who had pulled the plug on one of his more ambitious investigations – that he was the ‘best f**king friend organised crime ever had’; and in yet another one he’s being presented with a bottle of Chivas Regal by Phillip Bradley, head of the NSW Crime Commission, who had lost a bet that McKay couldn’t lock up Tony Vincent, an untouchable Sydney crime figure of his day.

Friends called him ‘Slasher’, a nod to the 1950s and 1960s Australian cricketer with the same name and, aptly, a wink to his management style – he was a chainsawer of red tape, a commander with a never-ending budget allocation.

One time a federal police counterpart confided in McKay that he didn’t have the money to keep an investigation going. McKay just laughed and said: ‘It’s the government, mate, it’s never gunna run out of money.’

His journey to Stacey Street that afternoon had started an hour earlier at the Cronulla Hotel, a pub about forty minutes’ drive from Bankstown. The sky was overcast and strong offshore winds had killed off his plans to go sailing, a favourite off-duty pastime. He pulled up a bar stool and resigned himself to an afternoon of drinking with a few buddies. He was either on his first beer or fourth, depending on who’s telling the story, but just after midday his phone started vibrating. Private number.

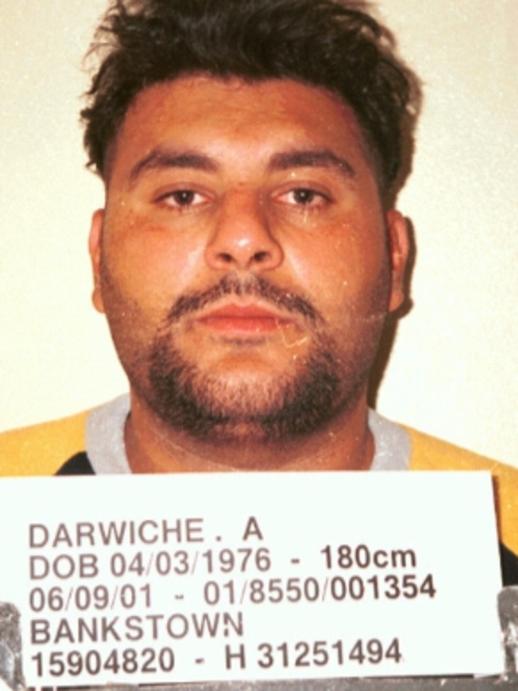

‘I’ve got that thing,’ the voice said. It was male and vaguely familiar, a call McKay had been told was coming, part of a secret deal that his detectives had hashed out with Adnan ‘Eddie’ Darwiche.

Housed behind the five-metre walls and concertina wire of Lithgow Correctional Centre, Darwiche had first revealed in a series of clandestine meetings with detectives Mark Wakeham and Jenny Nagle that he was prepared to hand back several rocket launchers in his possession if he could get a reduction on his murder sentences. They hadn’t been handed down yet, but he was facing life for the 2003 Lawford Street shootings that killed Mervat ‘Melissa’ Nemra and drug boss Ziad ‘Ziggy’ Razzak.

Nearly three years to the day after the incident, Darwiche had been convicted of the shooting by a jury. Aware that he may never see daylight outside of a prison, Darwiche was weighing his options. In that sense, the rocket launchers weren’t just a bargaining chip, but also a ransom demand, a pressure point not just for the police but also the national security services. Darwiche knew damn well they wanted those weapons back. If nothing else, he had everyone listening.

Wakeham and Nagle’s work had drawn out his first and only admission that he was currently storing, somewhere in Sydney, a number of rocket launchers that had been taken from the army.

Never made clear

Previously, this hadn’t been clear. The army denied that any were missing. McKay had joined the dialogue with Darwiche a bit later as these negotiations escalated. He had the rank and pull of a superintendent, and could make these sort of deals possible; but he wouldn’t be held hostage by big talk.

He had laid things out plainly for Darwiche, telling him his admissions meant nothing without some kind of proof. If he wanted to talk deals, he’d have to hand back one of the launchers to get the ball rolling. As a goodwill gesture, Darwiche said he would deliver one rocket launcher through an intermediary, who would call in good time. Deal, McKay said, and he would find a way to return the favour in kind.

And so it went: that afternoon at the Cronulla Hotel, the call came through. McKay hung up the phone, set his beer aside and started dialling numbers, putting together a team to head out to Bankstown to meet his mystery caller. First he called Detective Sergeant Belinda Dyson, a trusted colleague. Dyson was home, off duty, doing the washing.

‘What are you doing?’ McKay asked.

‘Nothing. Why?’

He asked if she had a gun.

‘Yeah, it’s in the safe,’ she said.

‘I’ll pick you up in ten minutes,’ McKay said. ‘Bring your shooter and your bullets.’

They took the M5 out to Bankstown, calling Mark Wakeham and Mick Adams along the way and arranging to meet them at Punchbowl Park. Adams, Wakeham’s team leader at MEOCS, had been pivotal to the Darwiche negotiations; a lateral thinker and a problem solver, it was his idea to get McKay to use his mobile phone as a makeshift listening device. He’d even had a warrant typed up at the office before arriving at Punchbowl so any admissions recorded over the line could, potentially, be used in a courtroom.

At Punchbowl Park they formulated a plan. Dyson would drive with Adams and provide security from a distance. Wakeham would stay with McKay and shadow him at the meeting. Their biggest concern was an ambush.

To let an unguarded commander walk into the heartland of Middle Eastern gang activity and pick up a rocket launcher linked to Adnan Darwiche seemed like an unwise move, especially without appropriate security precautions, of which they had none.

It was a five-minute drive from Punchbowl to the townhouse on Stacey Street where the two men were waiting. McKay picked up the launcher with a towel to avoid transferring any fingerprints onto it, then he walked back to his car and carefully rolled it into the boot.

‘That wasn’t too hard,’ he said, getting into the passenger seat.

They drove slowly back to the MEOCS HQ, careful not to let the device roll around too much in the back. No one knew the capability of the thing – would it go off if another car bumped into them?

Could it be activated just from rolling around? McKay knew the weapon had a safety catch, but he was damned if he knew where it was. He’d never seen a rocket launcher before. No one had. Tailing them close behind was Dyson and Adams who provided a buffer from other cars.

Back at the office they all posed for photographs with the launcher, hamming it up for the camera, gathering around it like a trophy. Naysayers had said this day would never come. Bets had even been taken around the office on how quickly this mission would fail. One guy had said he would run naked down George Street if they recovered it successfully.

Dyson called the Bomb Squad and explained the situation to an on-call supervisor: they’d just picked up a rocket launcher from a community source and needed an expert to come out and pick it up. The supervisor laughed. It was an obvious joke.

‘You’re geeing me up, aren’t you?’

‘No,’ Dyson said, deadpan. ‘It’s sitting here in the middle of the office.’

The supervisor’s tone darkened. He ordered her to evacuate the building as a matter of urgency and set up a clearance zone. Dyson said that wasn’t possible; the building shared its real estate with a police station that couldn’t just be cleared out. ‘There are guys in the cells downstairs,’ she said.

Another, unforeseen logistical problem soon emerged. In something of an ironic twist, the Bomb Squad was not equipped to store a live rocket launcher at its depot in Zetland. The same problem arose at every police station across the city as Dyson tried to find a suitable gun safe. No one, it seemed, had the capacity or willingness to babysit the rocket launcher they’d just recovered.

Normally, she would have just called the army, but that wasn’t possible either; giving back the weapon could tip off the person who had stolen it, and therefore jeopardise enquiries into how it went missing.

As a last resort Dyson called the Forensic Services Division. But they also refused to take the device for safety reasons. As the minutes ticked by, McKay began running out of patience. Sure, there were safety issues, but the meddling bureaucracy of it all gave him the shits. His team had just brought home the most sought-after weapon in the country and suddenly no one wanted to go near it.

‘Well, where the f**k are we going to put it?’ he asked, loudly. ‘We can’t just leave it in our office.’

He called back the Bomb Squad and pulled rank with the supervisor, coming up with a deal to reach a compromise – if their people could just pick up the launcher and store it for the rest of the weekend, then the Australian Federal Police would take it into their charge on Monday. Fine, said the supervisor. A forensics officer tried to examine the device when it arrived at the Bomb Squad’s depot but was so nervous about touching it that only a few surfaces were given a dusting.

That Monday morning it was taken from the Zetland depot to the AFP’s headquarters in Sydney’s CBD. Forensic technicians went to work on the device. They pulled it apart until it was in pieces on the floor, removing its wings and examining its panels for any serial numbers. Each component was run through an X-ray machine to find any details that might have been scratched off. Envious types in the MEOCS office joked that the weapon was probably a dummy, nothing more than a tin tube handed over by a scheming criminal wanting a discounted prison sentence.

When the AFP was done with its examination they sent a 24- page report back to Detective Sergeant Mick Adams with their findings, concluding, in no uncertain terms, that the launcher was not a fake. A full profile of the weapon followed. The device was an M72 Light Anti-Tank Weapon, model number L1A2-F1, assembled using imported parts (the ‘M’ in M72 denoting manufacture in the United States) at an ammunition-filling factory in St Marys, a suburb of western Sydney. The launcher had been fitted with a high-explosive, Norwegian-made A3 warhead that had detonated on impact during live test firing in Adelaide. These tests showed the missile had been capable of penetrating twenty-eight centimetres of steel plate, seventy-five centimetres of reinforced concrete or 180 centimetres of soil.

Records suggested the weapon had been brought to Sydney around 1990 or 1991 for assembly, had a lifespan of about a decade, and was one of several devices scheduled to be destroyed on 8 June 2001 at the Myambat Ammunition Store near Muswellbrook, an army outpost several hours north of Sydney. Somehow this had never happened.

Whoever stole it seemed to have a thorough working knowledge of where the important serial numbers were located, because they were all scratched off. But they were sloppy with the warhead itself. Its unique identifier, RAN90, was still intact on the side of the rocket fuse, allowing a trace to begin.

As McKay noted in a memorandum to superiors much later, the recovery represented a reality check for law enforcement, proof of the raw power at the fingertips of some MEOC identities. It was also a massive coup for the fledgling Squad; barely five months after its formation its detectives had not only recovered a weapon of enormous significance, but they had also confirmed that a much larger stockpile was still in the community, somewhere. Most concerning of all was the people with access to the devices, jihadists looking to cause heavy casualties in a civilian setting.

‘For a number of years there had been talk within the criminal community of the existence of rocket launchers,’ McKay wrote in his memorandum, a circular that went high up the chain of command.

‘The validity of the information was difficult to judge. As a result of this investigation we now know for a fact that this weaponry exists and is [in] the possession of criminals/terrorists.’

- The Squad by Yoni Bashan is published by HarperCollins.

- This extract was first published by The Daily Telegraph in July 2016.

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout