Death in custody: Children of Aboriginal elder Kenneth Ken sue South Australian government over loss of cultural knowledge

Six years after an Aboriginal elder took his life in prison, his grieving children have launched unprecedented legal action for the loss of his ancestral secrets and cultural knowledge.

SA News

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

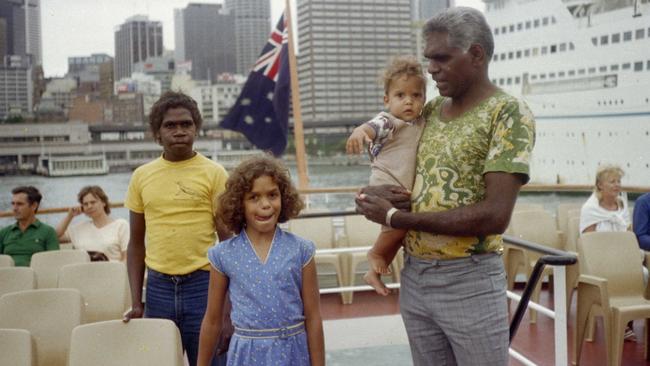

Aboriginal elder Kenneth Ngalatji Ken traversed two cultures for decades before his eventful life abruptly ended in a prison cell.

A committed Christian married to a white woman, he possessed vast traditional knowledge passed down from his ancestors across tens of thousands of years. He often would share his stories, family history and traditional practices with his two sons and two daughters, who were raised in the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) Lands before moving to Adelaide.

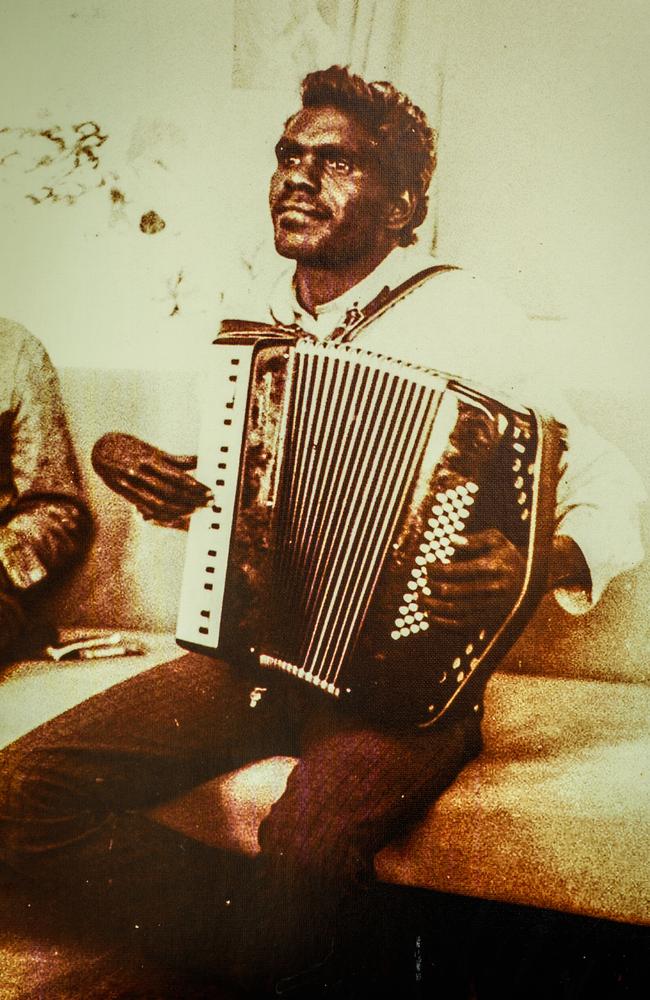

All of this came to a sudden halt when, at age 68, the music-loving Anangu man was arrested and put into prison for the first time in his life. Through an appalling set of circumstances later laid bare by a coronial inquest, Ken, who spent most of his life preaching the gospel in remote communities across Central Australia, the Northern Territory and Western Australia never left custody alive.

Instead, his four children are now suing the South Australian state government for $4.5m, not just for the neglect which saw their father take his own life but for depriving them and their children of his vast cultural knowledge.

Youngest daughter, Tjunkaya, says she and her siblings see the legal action as the only way they can hold the government to account and force changes to help other Aboriginal people avoid the same fate as their father.

“Our culture has never been broken before and now it has been,” she says. “It was preventable, very preventable.”

The Adelaide lawyer representing Ken’s four children, Joshua Michaels, says the case is a legal first for Australia. He is using 110 pages of damning findings by Deputy Coroner Anthony Schapel, to mount the compensation claim.

“Nobody has ever asked any Supreme Court to put a monetary value on an Aboriginal person’s culture and beliefs before,” he says.

In his comprehensive findings, handed down after an investigation which spanned four years, Schapel detailed a chain of events which began in mid-March, 2015, at Port Augusta and ended four weeks later with Ken hanging himself while suffering a heart attack at Yatala Labor Prison in Adelaide.

“It is no exaggeration to say that from the time Mr Ken was received into the custody of the Department for Correctional Services (DCS) in Yatala, the duty of care that is owed by DCS to prisoners in their custody was conspicuously neglected in his case,” he wrote.

“It is almost as if every historical and contemporary correctional failing of care was carefully assembled and visited upon Mr Ken.”

The lodging of the compensation claim last month in the South Australian Supreme Court came 30 years after an Royal Commission into black deaths in custody handed down hundreds of recommendations to prevent Aboriginal people committing suicide while behind bars.

One of the key recommendations was for hanging points to be removed from prison cells, exactly like the bookshelf which Ken used to tie a sheet around his neck while he should have been under continuous observation at Yatala following a previous attempt at self-harm.

How he came to be in such a predicament began with his arrest and court appearance over an alleged incident of domestic violence at Port Augusta, hundreds of kilometres from Ernabella in the APY Lands, where he was born in 1946.

As a young Anangu man, KennethNgalatji Ken had undergone a rich cultural education from his elders before he met young teacher Sandra Preisig at Amata in the late 1960s.

The adventurous 21-year-old churchgoer had driven to the APY Lands in a brand new Toyota Land Cruiser, which she had bought after spending her first year out of teacher’s college at Streaky Bay.

Sandra had become determined to work with Aboriginal people as a teenager. During her childhood she spent time at Indigenous campsites near her home in the Victorian town of Merbein South, on the banks of the River Murray. She jumped at the chance to work in the lands when its first school opened at Amata in 1968.

A talented musician, Kenneth would go to the school to play the guitar for Sandra’s pupils while she taught them songs. Over time, the pair became friends, with Sandra using her Land Cruiser to teach him to drive. They later were married at a church in Adelaide’s western suburbs.

The newlyweds spent four years living in Amata before moving to Whyalla, where Sandra continued working as a teacher. She then moved to Adelaide for two years to study theology while Kenneth went to the Aborigines Inland Mission Bible College in the Hunter Valley.

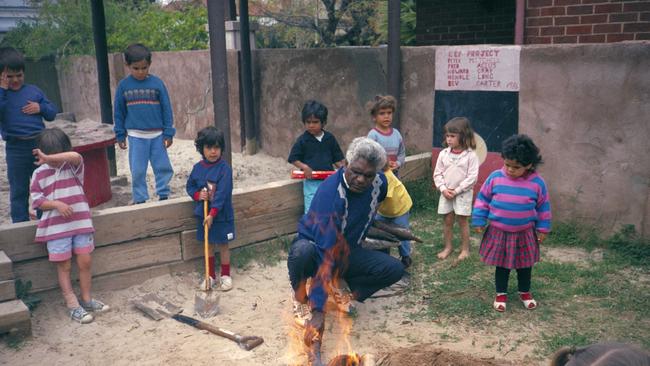

The couple returned to the APY Lands, where Kenneth took up evangelical preaching in remote communities across Central Australia, the Northern Territory and Western Australia while Sandra kept teaching and caring for the children of Anangu relatives brought home by Kenneth.

“He was a very studious, academic man who could spend the day reading the bible, taking notes and writing sermons,” Sandra recalls. “He went everywhere. He did it for quite a few years. He had a very good understanding of the bible.”

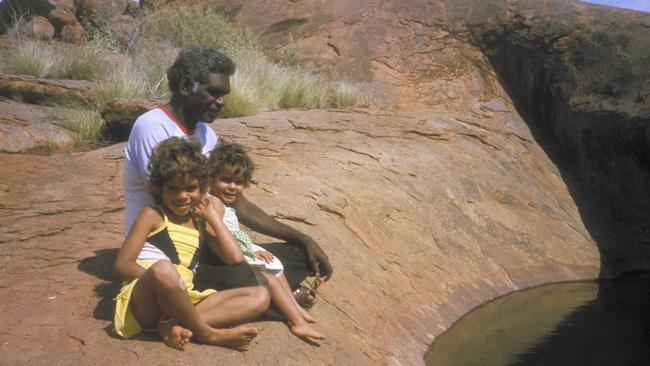

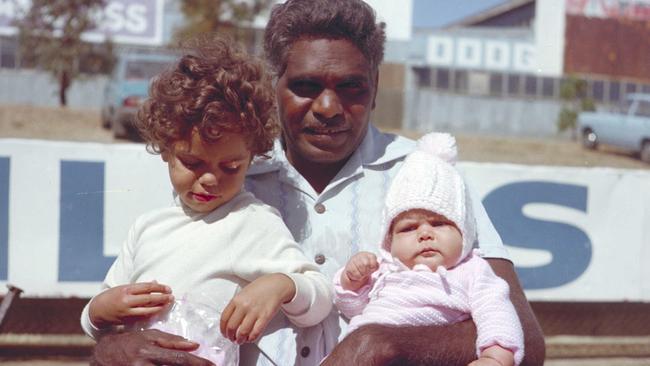

The couple’s first child was a girl, Rebekah, followed by another daughter, Tjunkaya, and two boys, Aaron and Joel. While growing up at Amata, Kenneth would talk to them about their ancestry, share Tjukupa (Dreaming stories) suitable for children and take them exploring, explaining the intense relationship between their people and the land which spanned centuries.

“Ken was a very loving father, a good father,” says Sandra. “He was a thoughtful, kind and generous man who loved his books, his reading and his music. He played the guitar, told stories, sang songs. He was fun when he was doing what he enjoyed.”

The family moved to Adelaide when Rebekah was 12 so she could complete her secondary education. Over the next decade, Kenneth and Sandra provided accommodation for other APY teenagers coming to Adelaide to study. Their relationship became strained when he began drinking heavily in his new urban environment. They separated in the late 1980s.

Kenneth returned to the APY Lands, where he continued to spend time while they lived at Ernabella with Sandra, who had moved back once her children had finished secondary school. He continued to share his cultural knowledge as an elder and recognised community leader who had been heavily involved in lands rights campaigns.

Sadly though, heavy drinking would remain an issue, and he was arrested on March 24, 2015, for allegedly assaulting his de facto partner, an Aboriginal woman from the Northern Territory.

Kenneth Ngalatji Ken appeared in the PortAugusta Magistrate’s Court charged with aggravated assault on March 25, 2015, where a young lawyer from the Aboriginal Legal Rights Movement did not apply for bail. He was remanded in custody and taken to the Port Augusta Prison.

Over the next fortnight, Ken became increasingly delusional and agitated, telling prison officers he was receiving threats and having visions of people from the Northern Territory making themselves invisible and coming through the walls to take revenge for the alleged assault on his partner.

Having suffered from high cholesterol, chronic renal failure and high blood pressure, Ken was not in the best of health, physically or mentally. He first came to the attention of prison medical staff when he tried to hurt himself by jumping from the top bunk in his cell on April 4, 2015, injuring his arm.

The inquest into his death heard Ken’s next attempt at self-harm was three days later, when he tied a shirt around his neck and tried to choke himself. This prompted the prison’s management to put him “on canvas”. This involves suicidal prisoners being given canvas smocks and bedding to minimise the risk of tearing up cotton sheets or clothing to use as nooses.

Port Augusta prison management issued a formal notice of concern declaring Ken a high-risk inmate. Under statewide guidelines, the prison’s doctor, Dr Lorelei Sabio, prepared a mandatory welfare plan. This included instructing nursing director Melissa Allen to request a transfer to Yatala Labour Prison in Adelaide so Ken could receive an urgent psychiatric assessment. Allen emailed her counterparts at Yatala on April 9, seeking an appointment.

She told them that Sabio wanted Ken to be kept under constant surveillance to ensure he did not make another suicide attempt. Allen said Sabio also suggested he should be put in a cell with a camera with another Aboriginal cellmate of similar age and kept away from the prison’s mainstream population. Allen recommended the best place for him was the prison’s infirmary where he could be kept under constant observation.

Ken was transported by road to Adelaide with his case file five days later on April 14, after Yatala staff sent an email confirming he would be kept in the prison’s “health centre”. Instead, upon his arrival, he was processed and put into a double-bunked cell without a camera with another inmate because he told staff he wanted to smoke.

His appointment to see a psychiatrist the following morning during a three-hour clinic did not proceed because of an administrative error. Ken was bumped to the bottom of the list and not seen by the consulting psychiatrist because of a daily lunchtime lockdown when prisoners were kept in their cells for two hours. Another appointment was made for him to see a psychiatrist the following week.

It was while he was in his cell later that day that Ken believed he heard other Aboriginal inmates shouting at him. He became distressed, prompting his cellmate to alert prison guards.

The inquest heard nurses Sylvia Mosey and Michelle Dunn were sent to check on Ken, who told them the other prisoners were threatening to kill him and members of his family. Mosey and Dunn recommended he should be moved to the infirmary so he could be properly assessed and watched. The pair’s supervisor, Sarah Legg, went to the cell and spoke to Ken through its trapdoor.

Legg decided he could remain there for the night, asking him to sign a form providing his written consent. The decision was later supported by the prison’s night manager, Oliver Goels.

The next morning, Ken was receiving a daily check up from another nurse, Duc Le, when he recorded a high blood pressure. The inquest heard he told Le that people “are trying to kill me tonight” and he had chest pains. Le decided to take him to the infirmary for an electrocardiogram (ECG) examination, which showed “borderline” readings between normal and abnormal. His file contained similar results from an ECG taken while he was in Port Augusta Prison.

Le took the ECG results to the infirmary’s doctor, Allan Moskwa, who was in another room. According to the inquest findings, he looked at the printouts, said Ken “was fine” and could be returned to his cell. Moskwa did not examine or talk to him before he was taken back. Before he left the infirmary, Ken told two prison officers he thought he should be taken to hospital.

It was almost lunchtime and time for the prison-wide lockdown when Ken was taken to a different cell. Despite the mandatory requirement to have a cellmate and being on a suicide watch list, he was left on his own because the other prisoner was making a video court appearance.

As Ken’s chest pains started to worsen he tied a sheet to a bookshelf, sat on a chair and hanged himself while he suffered a fatal heart attack. He was discovered when his cell door was opened two hours later. Attempts to resuscitate him were unsuccessful and he was pronounced dead at 1.55pm on April 16, 2015.

In his findings, Deputy State Coroner Anthony Schapel detailed a litany of systemic failings and circumstances which contributed to Ken’s death. The highly respected judicial officer did not pull his punches, describing the way Ken was treated in custody as “perplexing”, “puzzling”, “manifestly inadequate”, “nonsense”, “inappropriate” and “inflexible”.

Schapel said the “number of egregious circumstances that befell Mr Ken since his transfer from Port Augusta to Yatala” ranged from various managers and prison officers not following the mandatory requirement to keep him under constant surveillance to failing to read his file containing details of his two previous attempts at self-harm.

“It is my finding that the processing of Mr Ken upon his arrival at Yatala and the decision to not place Mr Ken in the infirmary was flawed,” he wrote. “The decision miscarried because important communications were either not passed on or acted upon.”

Schapel was particularly concerned about how various Yatala staff who gave evidence during the inquest told him they were unaware Ken was a suicide risk, despite the detailed file sent with him from Port Augusta. He described some of their responses to questioning as “rather lame”. “There was an almost universally asserted claim that nobody knew that Mr Ken needed to be doubled up at all times during lockdown,” he wrote. “This unedifying circumstance meant that it was virtually impossible for this Court to accurately reconstruct how it was that Mr Ken’s HRAT (at risk) status was overlooked and how the need for him to have been doubled up during lunchtime lockdowns was also overlooked.”

Mr Schapel saved some of his harshest criticism for Moskwa, describing the long-serving prison doctor’s clinical management of Ken before sending him back to his cell when he was suffering chest pains as “simply inadequate”.

“The circumstances that prevailed did not preclude Dr Moskwa from examining Mr Ken and asking him appropriate questions,” he wrote. “They did not prevent him from examining Mr Ken’s prison health service records or from establishing Mr Ken’s relevant medical history.”

Schapel found Ken should have been kept in the infirmary “at least for observation and not have been sent back” by Moskwa to his cell, where he was left unsupervised for two hours, during which he took his own life.

Ken’s family first learnt about his death not through official channels but from relatives at Amata, who received a call from police on April 16, 2015, informing them that he had died in custody earlier that day. This was despite his youngest daughter, Tjunkaya, being listed as his next of kin.

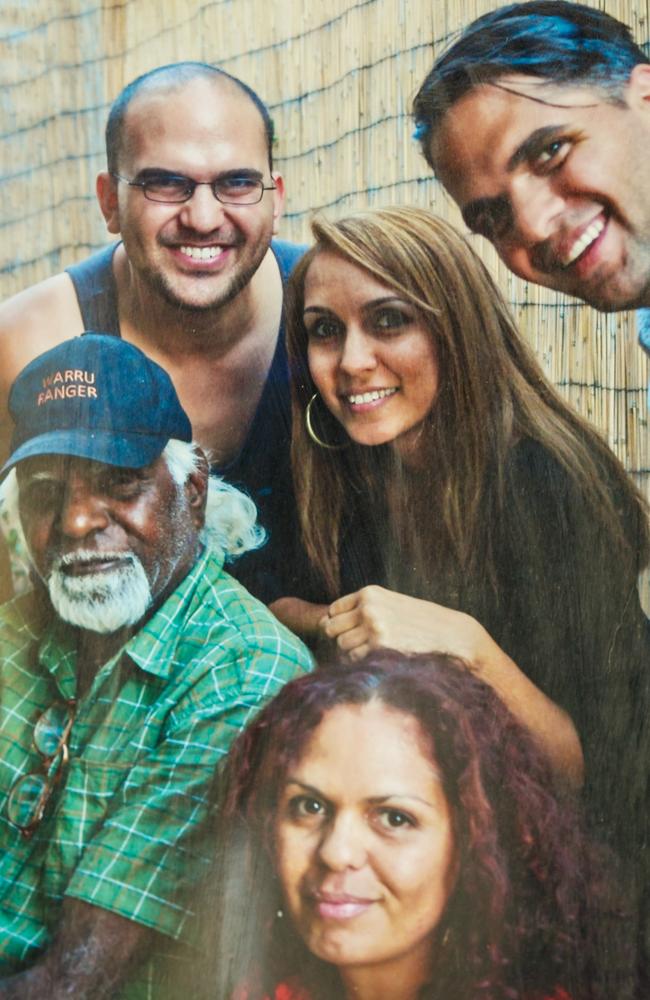

Tjunkaya, 41, was with her siblings Aaron, 37, Joel, 34, and Rebekah, 45, having dinner at their mother’s house at Queenstown, near Port Adelaide, when they started receiving the tragic news from the APY Lands, where Ken was a revered and popular figure.

“Everyone knew Dad had a family in Adelaide,” says Aaron. “We couldn’t believe they (the authorities) were ringing our relatives in Amata and not calling us first, especially when Tjunkaya was down as his next of kin. When we rang the prison chasing it up we spoke to them in good English. They sounded shocked and said they needed some identification. I truly believe that they thought we were white because of our voices.”

Sandra Ken says she remains upset that nobody from her family was contacted while her estranged husband was in custody, including when he twice attempted self-harm while at Port Augusta.

“You would think that when someone is suicidal, they would contact someone from the family in case they can help settle them,” she says. The family’s treatment by the Department of Correctional Services is part of the Ken children compensation claim, which not only seeks damages for the various procedural failings but also how the death of their father has caused them significant cultural loss.

Their statement of claim lodged with the Supreme Court says the four, all social workers, depended on Ken “not only as their father but culturally, in that Anangu elders take care of the community and hold the knowledge that all members seek to gain.”

“That knowledge is acquired through one’s lifetime, where individuals earn the right to progress through stages of initiation into ever more complex layers of cultural knowledge,” says the claim. “That means the cultural knowledge is learned slowly and over a lifetime. The applicants were dependent on Mr Ken to understand each Tjukurpa (Dreaming or Dreamtime to the Anangu people) as it is different for each maternal or paternal line.”

Because their mother was white, Ken had to pass his cultural knowledge to both his sons, daughters and grandchildren.

“The applicants were culturally dependent on Mr Ken, as he advocated his culture and practised his craft regularly with the applicants,” the statement of claim continues. “The applicants’ non-Aboriginal mother is unable to do that, and the applicants have been denied the opportunity of cultural knowledge which they would be able to pass onto their children.”

Joel Ken, who is a mental health worker in Ernabella, says his father was not only a Christian but a tribal elder who still practised his traditional beliefs and practices.

“With his loss we have lost a voice,” he says.

“We are not doing this because we are anarchists, or anti-government. We are doing this to try to stop it happening to other Aboriginal people.” Aaron Ken agrees, saying that while Aboriginal people living in urban environments largely have had their traditional practices crushed by colonisation, cultural law (Tjukurpa) remains an integral part of life in the APY Lands. “We still have our culture,” he says. “We still have our ceremonies and our Tjukurpa (Dreaming).”

Aaron, the chairman of Aboriginal community organisation Iwiri, says culture is “currency” for people from the APY Lands, not material assets such as houses and cars.

“Knowledge is your power, your wealth,” he says. “That wealth, that knowledge, is given to you. It is your identity. Elders are so powerful because they have the knowledge.

“Now our father has gone and is not able to pass on his culture to us anymore. That is why we are doing this. Our father used to take it to the government. He would be proud of what we are doing.”

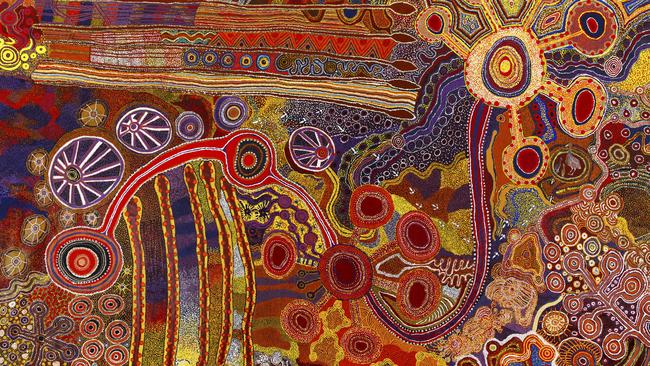

HUGE MURAL IS ELDER’S LASTING LEGACY

KENNETH Ngalatji Ken’s lasting legacy is a huge mural painted by dozens of Anangu people from the APY Lands. The 5m by 3m canvas artwork was conceived by Ken’s four children to draw attention to Aboriginal deaths in custody, including the suicide of their father.

It was started near Uluru at the Yulara Resort in late 2020, when Anangu from the APY Lands were invited to perform for guests.

“We took a whole bunch of singers and dancers up in a coach and worked on the mural between performances,” says Aaron Ken, the chairman of award-winning APY community organisation Iwiri. “We brought it back to Adelaide, and told family they could come and help finish it.”

More than 70 people contributed, many of whom had also been either affected by a death in custody or had a loved one in prison.

“It started as a tribute and became a catalyst for all of our family members in prison that we are worried about,” says Aaron. He says his family is looking for a permanent home for the mural, which tells Tjukurpa (Dreaming) stories about Anangu people who have lost their lives or been incarcerated.

Iwiri is based at the Taoundi College at Port Adelaide where Anangu people living or visiting Adelaide regularly gather to paint and provide support to each other. Art produced in recent years will be sold at a Port Adelaide market, Mixed Creative, on December 12.

■ The Advertiser and News Corporation was given permission by Kenneth Ken’s family to use his name and his photograph. If you or someone you know needs support, call Lifeline on 13 11 14 or visit lifeline.org.au

Originally published as Death in custody: Children of Aboriginal elder Kenneth Ken sue South Australian government over loss of cultural knowledge