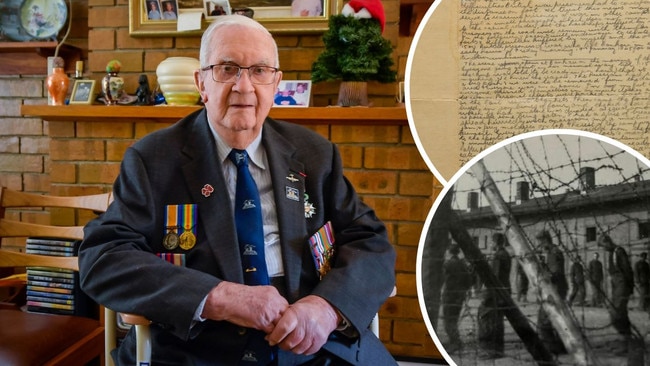

Angus Hughes survived a Nazi prisoner of war camp – and kept a secret diary to remember the horrors

When Angus Hughes’ plane was shot down, he spent days dodging the Nazis with the help of a compass hidden in his tunic button. But Germans caught him – and the true horrors began.

SA News

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

When it comes to an unassuming war hero with an extraordinary story, it’s hard to go past Adelaide man Angus Hughes.

The gentle, quietly spoken retired accountant celebrated his 100th birthday last October and is believed to be the state’s last living survivor of a WWII German prisoner of war camp.

Days before his 21st birthday, he was captured after his plane was shot from the air over Germany by the Rhine River.

He would first spend three days by himself, trying to find his way across the river to safety in Switzerland.

Mr Hughes enlisted to serve his country on his 18th birthday but wasn’t called up to join the RAAF until he was 19, in July 1942.

He completed navigation training at several South Australian RAAF bases, including Mt Gambier and Port Pirie, before being deployed to the UK in July 1943 where he completed heavy bomber conversion training and joined 467 Squadron, stationed at RAAF Waddington in Lincolnshire.

From here, he’d serve as a navigator and bomb aimer, in air operations lasting up to eight hours at a time.

It was on his 32nd mission in late September, 1944, that his crew’s Lancaster aircraft was hit by enemy flak forcing himself and his five fellow crewmen to “bail out”.

“We were just flying along getting close to the target and we got hit out of the blue ... there was no warning and no way of knowing because we were that high you couldn’t see the flash,” he says.

“The pilot couldn’t put it out with his fire extinguisher and we just had to bail out – it was just automatic, what we’d been trained to do.

“I had to jump out the front hatch, but it was jammed, so I had to kick it out.”

Sadly, one didn’t make the more than 3500m drop to the ground – the mid-upper gunner was last seen at the rear escape hatch – with the other four captured on landing.

“I was just fortunate, when I came down I landed through a tree, close to a little creek,” he says.

“I buried my parachute and jacket and took off all my insignias, as we’d been instructed to do. I just stopped there until it started to get light and I could get my bearings.

“We had a safety packet that contained nearly everything, there was money – German and French – as well as a map, very hard compressed food, a water bottle and a tablet to purify the water.”

A compass was set in a tunic button and his boots were designed to look like civilian shoes when the tops were cut away.

“I started to head down towards the Rhine, picking up bits and pieces (of fruit) from an orchard on the way but I had a terrific headache,” he says.

“There were some French (workers) doing some gardening under instruction from the Germans and one gave me an Aspirin-like tablet to help with my headache.”

He spent a second night sleeping on the ground before making his way to the river border only to find it was flowing too quickly to cross.

“There was a series of canals and a pumping station … I swam across one of the canals but then didn’t know what to do, so swam back to the pumping station and slept there the night,” he says.

The next morning, after swimming back across the canal he was caught by a German guard and taken to a prison where he spent about a month before being moved to an interrogation centre in Frankfurt and later to the first of two prisoner of war camps he would spend the remainder of the war – Bankau in Poland.

When asked about this time and the treatment he received, he’ll quietly admit to being “knocked around a little bit” but is stoic in his response.

“It was just a matter of living, that was all … I was just trying to keep alive, that was it,” he says.

For him, the hardest challenge was surviving a more than 200km forced march which lasted for 21 days in the most bitter of European winters, traipsing through frozen countryside in the clothes he’d landed in – being fed a single piece of bread a day.

A decision had been made to move the POWs to Germany – Stalag Luft VII at Luckenwalke – as the Russians advanced.

“It was absolutely freezing cold,” he says.

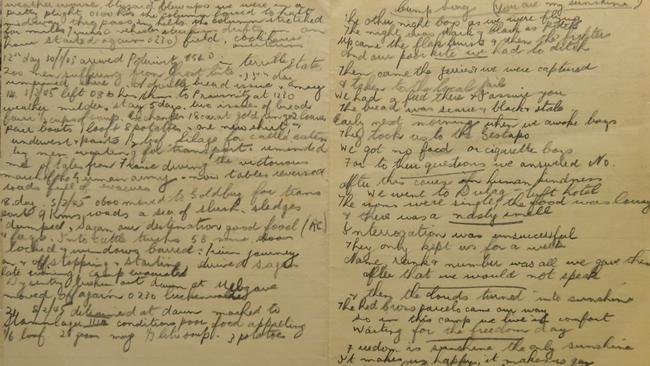

He kept a diary of the unimaginable walk, secretly detailing the daily events on a piece of paper he kept hidden from his captives.

“Arrived in terrible state, 200 men suffering from frostbite,” he writes at the end of the 12th day.

There’d be more uncertainty, even after surviving the gruelling trek to the German camp he describes in his diary, noting “conditions poor, food appalling”.

“It was a hard camp and nothing like the 1960s TV show Hogan’s Heroes ... I sometimes wonder if that show is the reason why people think it wasn’t as hard for us (as those in Japanese POW camps),” he says.

“Hitler at one stage apparently made a statement that all the POWs had to be shot, or killed … we were marched out to this big long trench – we were on one side and the machine guns and all that were on the other – and we were there for about a quarter of an hour before we were abruptly taken back to our quarters.”

While they were never given an explanation, he believes they were saved by the knowledge the British and American armies “were very, very close”.

Still, after being liberated by the Soviet Army in May 1945, the POWs were held by the Russians for a month before they were released with Mr Hughes snatching the files his German captives had on him, as well as photographs from the camp’s records office.

Almost eight decades on, the moment of youthful rebellion still brings a smile to his face, revealing a glimpse of the cheeky young man who went to war.

He’d finally get home to Australia in December 1945 after several months recuperating in the UK.

“We had to recover ... we’d all lost a lot of weight and they wanted to make sure we were fit,” he says, recalling the utter joy of “a good bath and clean clothes”.

On his wall, in pride of place, hangs a framed letter of gratitude from the French Government issued when he was awarded a Royal Order of the Legion of Honour, the highest French order of merit, both military and civil.

It is memories of the friendships and bonds he formed – “some of the British fighter pilots were pretty good blokes” – that the gentle man who lost his childhood sweetheart wife, who was also a member of the Women’s Auxiliary Australian Air Force (WAAAF), in 2002, focuses on most.

But he admits he remains haunted by the experience of war.

“Oh yes, even now I will get nightmares … not every night but occasionally I will wake up (in a sweat) … thunder will do it to me if I am laying in bed and wake to it,” he says.

“I don’t think the people today realise what (war) is actually like ... it’s surprising how old a few years like that make you.”

He shuffles through the documents he retains from those days, including the words of a “camp song” that refers to keeping tight-lipped during interrogation and the comfort in “Red Cross parcels”.

Included in the handwritten lyrics: “The rooms were simple, the food was lousy and there was a nasty smell; freedom is sunshine ... it makes us happy; despite the hardship ... our mates will win the day ... when the day comes we are free, dear, I’ll come back home with you to stay.”

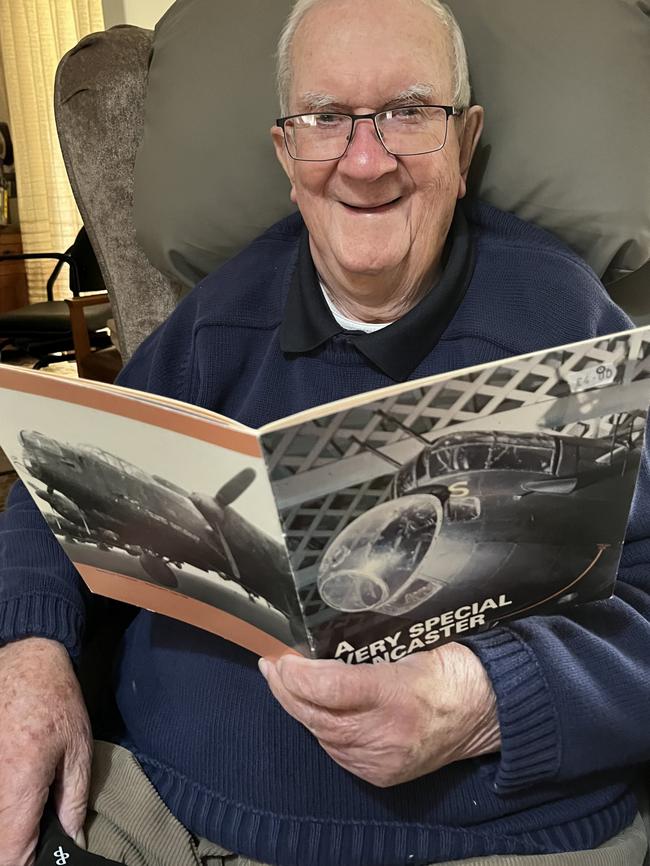

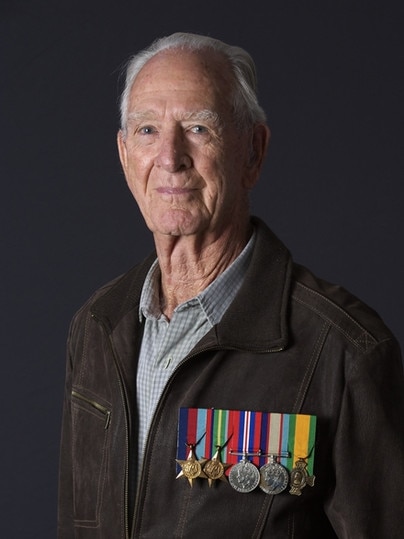

Lyall’s the last man standing from his squadron

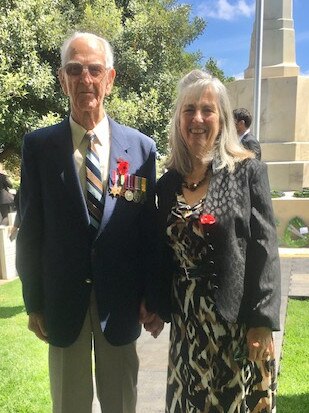

There’s one annual event World War II veteran Lyall Ellers holds above all others – Anzac Day.

This year he’ll be at the Adelaide parade with his Melbourne-based son Grant, himself a 30-year RAAF veteran and former squadron leader.

“It will be pretty special to attend with Grant, who is coming over especially for it,” the 100-year-old fighter pilot and last living member of his Royal Australian Air Force squadron says.

“(I’ll be thinking) about all my mates that aren’t here.”

Born in Perth, he enlisted at 18 in the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF), along with his older brother, John.

“Our father was a Great War veteran – he saw another war on the way and the idea greatly worried him,” Mr Ellers says.

“Our eldest brother, Frederick, had already been serving in the RAAF for a year … sadly, Fred was killed in a RAF Bristol Blenheim crash in India just as we came out of training, ready to play our part.

“After completing our flying training in Western Australia, I was chosen to go into fighter aircraft, and was posted to Deniliquin, New South Wales, to fly Wirraways.

“At 188cm tall, I was one of the tallest fighter pilots!”

Mr Ellers went on to fly in Squadron 4 in Papua New Guinea, and later Squadron 78, where he supported military forces by providing close air support, in 1942.

He also flew in other squadrons and various planes, including Kittyhawks and CAC Boomerangs, which were the first combat aircraft constructed and designed in Australia and used mainly for home-based squadrons to free up other fighters to go overseas.

“My service in 78 Squadron continued through to 1945, by which time I was stationed in Borneo,” he says, describing his fighter pilot days as “rewarding”.

But the role, which extended to the Solomon Islands campaign, wasn’t without its challenges and included navigating “risky, low-level flying” among the mountainous terrain and Japanese air defences of New Guinea, operational flying in the Dutch East Indies, and also an emergency landing in a Wirraway in Victoria.

After the war ended, Mr Ellers returned home to WA, discharged from the RAAF in 1946 as a Flight Lieutenant.

In 1954, he and his family moved to South Australia, settling in Seacliff.

The family flying legacy has been passed down with the four children of Mr Ellers and his late wife Pat – Christine, Maria, Grant and Allen – all working for a time in the RAAF.

The keen lawn bowler, who turned 100 in September, says he doesn’t allow his age to bother him, continuing to live life to its fullest.

“I don’t worry about it, I don’t think about it … as long as I stay alive, I’m quite happy,” he says.

More Coverage

Originally published as Angus Hughes survived a Nazi prisoner of war camp – and kept a secret diary to remember the horrors