Adelaide University pathologist Professor Roger Byard is lifting the lid on the fear of being buried alive

Adelaide University pathologist Professor Roger Byard has studied claims of people being buried alive – and the results may shock you.

SA News

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

There is good news from an Adelaide forensics expert who says despite all the dumb ways to die, you are unlikely to be buried alive while unconscious.

Quirky Adelaide University pathologist Professor Roger Byard has studied claims that there was an epidemic of the problem in the past, and has published his findings in the international journal Forensic Science, Medicine and Pathology.

“The fear of being buried alive or taphophobia remains a significant concern for some people,’’ he said.

“In previous centuries reports of live burials were frequently promulgated in the media.

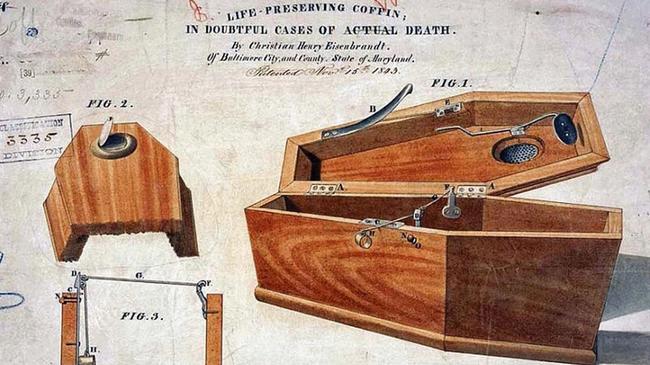

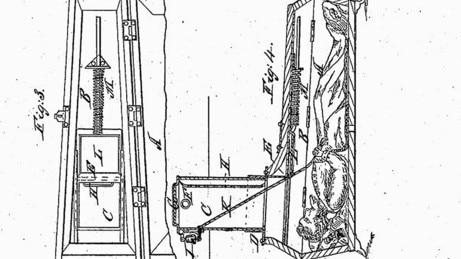

“There was an industry focused on selling coffins which let people escape or allowed live burial cases to alert those on the surface to their plight.

“Holding mortuaries with resuscitation facilities were also established to permit close observation of the recently deceased until definitive signs of putrefaction had developed.”

Professor Byard’s study was based on an analysis of literature that showed “most of the stories were not corroborated on careful examination”.

The study concluded that doctors should be careful when dealing with medical conditions or drug intoxications that may be associated with prolonged comas, and no medical-staff determining death was a problem.

“There is no doubt that alive burial remains a possibility, particularly in circumstances where there has been a mass disaster and where qualified medical staff are not available,” he said.

Professor Byard said behind the panic was the inability of doctors hundreds of years ago to diagnose death effectively.

He said instances that live burial had happened were common in fiction and word-of-mouth, and fuelled by a misunderstanding of what happened to the body some time after death.

People buried alive were thought to have destroyed their body shrouds and eaten their hands,

until it was shown this was done by rodents.

Other bodies were contorted into different positions than they had been buried, but this can be part of the natural process.

Popular horror writer Edgar Allen Poe wrote of live burial in 1844, and it was feared by prominent people such as George Washington, Frédéric Chopin, and Alfred Nobel.

Professor Byard said estimates of how common the fate was in the 18th and 19th centuries ranged up to one in ten deaths.

“Putrefaction was thought to be the only definitive sign of death, with later proposals

that absence of a heartbeat might also be proof were even treated with scepticism,’’ he said.

To avoid the problem, everything to identify death was tried; packing the nostrils with wool and sneezing powder, cutting the soles of the feet, putting insects in the ears, and pouring warm urine into the mouth.

Then acceptance of the putrefaction theory led to suggestions of holding mortuaries, so-called “Hospitals for the Dead” or “Asylums for Doubtful Life,” should be built to allow observation of the recently deceased.

Professor Byard’s study found that despite one of the mortuaries being built, in Germany, none of the more than one million corpses passing through from 1828 and 1849 had “woken”.

Later, with no scientific help forthcoming, an industry set up manufacturing escape coffins and models that could alert people on the surface to signs of life.

Available for purchase were coffins with breathing pipes to allow survival until rescue, levers designed to trigger alarms if there was movement of the head, ropes with bells, glass lids, and escape hatches.

Others had trumpets placed in the mouth and shovels and ladders interred with the body.

More Coverage

Originally published as Adelaide University pathologist Professor Roger Byard is lifting the lid on the fear of being buried alive