Wickedly funny, understated, control freak. Philip Bacon is widely recognised as Australia’s leading art dealer but there’s a lot about him the public doesn’t know.

It was painted by none other than Philip Bacon, when he was young enough to hope he might be an artist. The trouble is, he signed it under a pseudonym, and he can no longer remember the name he chose, or to whom he gave it.

On a steaming Brisbane summer public holiday, Philip Bacon sits in his airconditioned office at the celebrated art gallery bearing his name on the corner of Brunswick and Arthur streets, Fortitude Valley. He turns 77 in February, the same month his gallery marks its 50th anniversary, but it’s just another working day for him. Retirement? Hardly.

He’s chuckling – his friends know how wickedly funny he can be and every single one of them mentions it – because to Philip Bacon the story about his lost painting proves how much of contemporary art is smoke and mirrors.

“I knew I couldn’t draw, but it was the ’60s and people were painting large abstract paintings and I thought, ‘I bet I could do that’. So I did – big, smeary sort of pictures in colour, quite large – and they really weren’t too bad,” he says. “I can’t remember what name I used but I remember there was a big yellow one, a yellowy abstracty thing which my mum framed, or I did.” No Philip Bacon signature for posterity then?

“I didn’t sign it because I thought it was a con. It proved to me that a lot of abstract paintings were just a pile of poo, and I still think that.” Lest anyone think Bacon is making the clichéd “my-three-year-old-could-do-that” remark beloved by contemporary art sceptics, there are many abstract artists whose work he admires: “Ian Fairweather, say, who paints really abstract pictures, but he won the drawing prize at the Slade School. He knows about drawing – I knew I didn’t know any of that, so I never believed anything I was doing was of any consequence, except from a decorative point of view.”

In other words, Philip Bacon knew early the difference between real art and faux art, between artists and con artists.

THE SHAPING OF A GENEROUS OLD SOUL

Philip Bacon was born into a Catholic family in rural Victoria – his mother, Joan, came from a family with properties and his father, Jack, was a store manager and small business owner who had served in World War II. The family moved to Queensland for the warmer climate when Bacon was a child. He was the second child of four – an older sister, Robyn, a homemaker who still lives in Queensland, followed by two younger brothers, Brian, a retired entrepreneur now living in Hawaii, and Russell, an acclaimed cinematographer living in Sydney.

The Bacons were not an especially cultured family – there was no art on the walls – but there were books and music. His was a peripatetic childhood: “Dad moved on a lot, he opened a business in Bundaberg for a time – which was an awful thing to do to my mother, really, who had never left Melbourne, all those cane toads and snakes – we were only ever anywhere for a year, maybe 18 months, two years.”

He admits to a spot of jealousy when he hears people speaking of old school friends because he has none. “As a kid, my father used to read books to us every night, no television obviously, and I loved reading. I had a little group of girl friends who were a bit older than me – I’m not even sure which town this was – but they lived up the road from us. They had a wonderful tree, it was probably not nearly as wonderful or as magical as I remember it, but we used to sit up there and read aloud to each other. We had a sort of junior book club, and I loved it.”

He didn’t like school. “I left before senior. I hated being young, I was grown up already! I was 33 when I was 16,” he says, laughing. “Everybody has a mental age, I know some people who are 16 and will always be 16. Well, I was 33 when I was 16.”

In this way, when other young people in the swinging ’60s were into protests, long hair, drugs and excess, young Philip was into well-cut clothing, Champagne, restraint and appreciation for art, opera and beauty.

If he inherited his love of good grooming from his late father – who died young of bowel cancer, at just 50, but not before he instilled in Philip the notion that it was bad manners to leave the house without polishing your shoes – he inherited his work ethic from both parents.

Russell Bacon says that while his brother followed their father in his respect for fine tailoring, he also recalls Philip in a very well-worn brown cardigan, clutching a cleaning rag, toiling away at the windows in the family home “without a champagne flute in sight!”

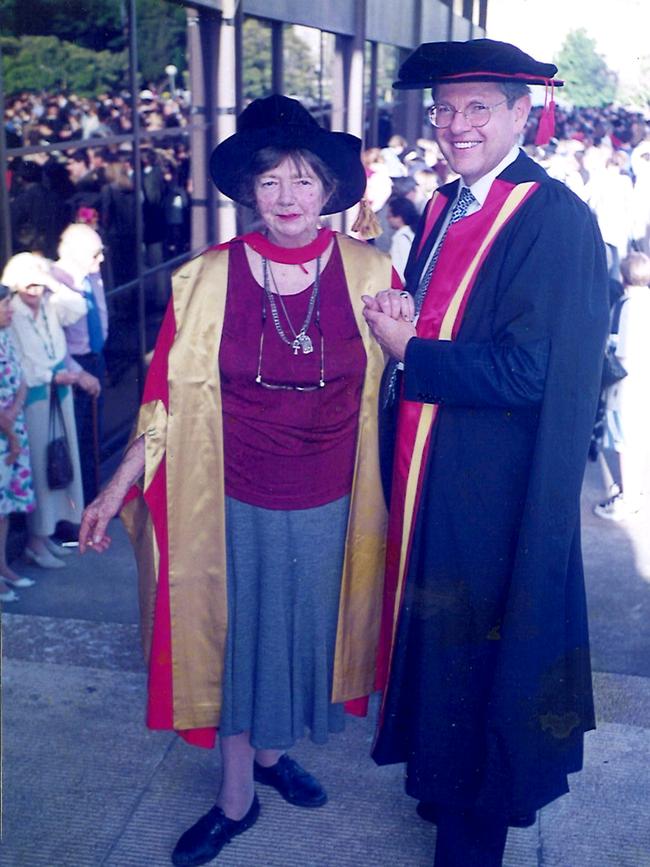

It was Philip who gave him his first Super 8 movie camera when Russell was 14, thus launching him into an award-winning career in TV (Packed to the Rafters, My Brother Jack) and possibly signalling the beginning of the elder Bacon brother’s generous philanthropy. Bacon was inducted into the Queensland Business Leaders Hall of Fame in 2019 for his outstanding contribution to philanthropy, and in 2021 he was made an Officer of the Order of Australia for his distinguished service to the arts, to social and cultural organisations and his support for young artists.

Bacon has long since shed the friendless days of his rootless childhood and is now a man secured by years of lasting adult friendships, by cherished routines, a much-loved home in West End, and a fulfilling life he has made his own.

His private generosity is less well-known: his old friend and client, fellow philanthropist Tim Fairfax, says although Bacon knows “everyone” he is scrupulously discreet, and what the public doesn’t know about is his generosity.

“He might pay for someone’s hospital fees, or he’ll pay for someone’s accommodation in an hour of need, or he’ll provide a refrigerator for someone or pay their mobile bill. He doesn’t seek repayment; it is a genuine gift.”

Another old friend, Dame Quentin Bryce, loves reminiscing with Bacon about the early days at the gallery and remembers it quickly establishing itself as a focal point for Brisbane’s cultural life. Those times were about “glamorous parties, cocktails, dinners, dressing up, architects, designers, would-be artists, gallery people who taught me about art, how to look at a painting. I soaked it all up”.

‘NEVER HAD A PLAN ... IT WAS SURVIVAL’

In 1974, 27-year-old Philip Bacon opened his eponymous gallery, with the help of a $20,000 loan from a friend’s father. By then he was in love with art and the art world and knew all three respected private galleries in Brisbane (the Johnstone Gallery, Moreton Gallery and the Grand Central Gallery where he worked for a time). He had long before made his first substantial purchase as a teenage collector – a lithograph by the French artist Bernard Buffet, which he hung at the family house, standing outside at night admiring it with the lights on and the curtains open.

By 1974 he’d finished night school, given up a law degree at the University of Queensland, and failed an attempt to please his dad by working in finance (“I was out at Dalby. I looked about 11 years old, and I was speaking to these crusty old farmers coming in for a loan to get them through the drought.”)

Bacon didn’t own his premises at first, but within the next few years the gallery was so successful he was able to buy not just the original premises but expand into premises next door. He lived over the shop then, before moving to an apartment in Torbreck in Highgate Hill and building his own house in 1986, where he has lived ever since (and which is graced with jaw-droppingly expensive paintings). Bacon is now a very wealthy man: he and his good friend and business partner, Brent Ogilvie, are co-owners of a big chunk of Noosa’s iconic restaurants and bars.

Fifty years ago, Philip Bacon couldn’t have predicted such success: “I didn’t know it would take off the way it did. I never had a long-term plan, I never even had a five-year plan. In the early days it was survival, really, it was year-to-year and there was always some crisis, but somehow, I seemed to survive them.”

He says he’s always been a control freak, from a business to a personal level: “All my other siblings have had at least one marriage. I determined very early that I was never going to be with anybody, I was never going to get married, not remotely interested. I have absolutely no private life! I’m too controlling to live with anybody, I really am.”

It’s work which enthrals Bacon, still: the paintings, the artists, the boards he’s on (including the Brisbane Festival, Opera Australia and the National Gallery Foundation), his business projects, the gallery itself: “I think why I love this business is that it’s constantly changing but also the same. I mean, the artists are changing, either themselves, or the artists are dying and others come along, the clients are always the same but they’re always different too. It’s really interesting for me to now be selling works I sold 50 years ago for the children of the people I sold them to, or for their trustees, either in bankruptcy or in death. Because you know there are three Ds in the art dealing business: death, divorce and debt, and that’s why people sell things.” His clientele has changed, too.

“When I first started in the ’70s, August was big in Brisbane. It was show week, all of the rich squatters came to town, the Queensland Club was heaving.” Then the cockies were replaced by wealthy doctors before they got too busy, and today it’s lawyers, CEOs, property developers.

He’s been lucky with his artists, too, with only a handful of fallings-out over the years. “You’re their banker, their source of income, their confidante, their enabler. My commitment to my artists is from the cradle to the grave.”

He’s aware his commitment to his artists often extends beyond their deaths: “I’m the executor of endless artists’ estates. You don’t do that lightly, the artist doesn’t, or their family doesn’t allow that to happen unless there’s trust.”

Bacon has never taken on an artist he disliked as a person “because usually one follows the art (he likes the art first). Artists are tricky, by their very nature, they’re selfish and one-eyed, they’re determined, ambitious and egotistical but a lot of that can be forgiven by their art, but if they’re vile human beings, I don’t want to be with them.”

SECRETS TO SUCCESS

He suggests one major reason he’s succeeded is because he’s never wished to live vicariously. “I’ve never wanted to live my life through (my artists). I think that’s a recipe for disaster, it’s the same as parents with their children – they live vicariously through the success or failure of their children – it’s desperate for both parties.”

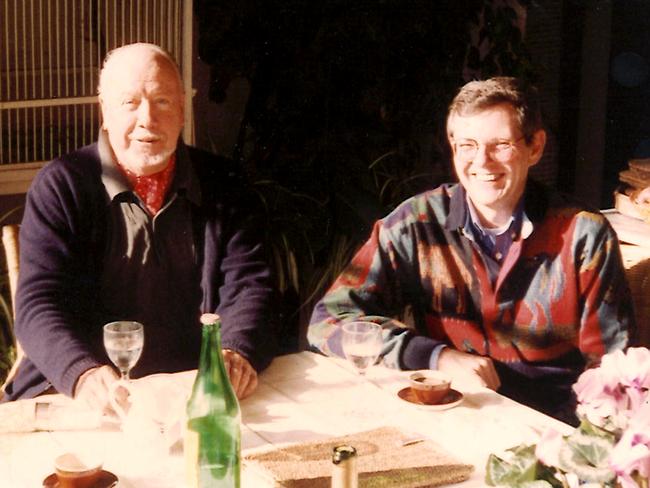

One long-time artist in his stable, William (Bill) Robinson, says he doesn’t rely on Bacon for emotional support either. “I had a wife, and my wife (the late Shirley) was my emotional support.” He suggests instead that Bacon has just the right personal qualities for an art dealer.

“He’s very funny, and you can have a joke with him. I once gave him a present of a ceramic cow I bought at the local paper shop at Manly – it was a cross-eyed cow with its legs all splayed, and he put it up on his shelf with his things as if it were another precious object that he had.”

His great friend Brent Ogilvie says Bacon’s friends love him for his irreverence.

“He’s very private and understated, and it takes a while to get to know him, but once you’re a friend, he’s incredibly loyal. He’s a creature of habit, too, one with a fierce work ethic. He’s so civic minded, on so many boards, passionate about opera and art and especially passionate about the gallery. The gallery is him, when he goes, the gallery will go. It’s him.”

For the moment Philip Bacon isn’t planning on going anywhere. “People say to me, ‘Oh, you’re retired now?’ and then they ask how often I go to the gallery and I say, ‘every day’. Every day is different and I’ve got wonderful staff but, you know, I’m controlling and I want to know what’s going on. And I like it, it’s interesting, fascinating.”

He scaled down the birthday celebrations too. “I’m not going to have any surprises around me!”

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

‘Woeful’: Calls for more Brisbane bridges sparks wild debate

Brisbane needs more and more bridges, according to a leading architect, but not everyone agrees. HAVE YOUR SAY

Jewellery store smashed up in midnight raid

Four men have smashed their way into a Logan shopping centre jewellery store overnight, destroying glass cabinets and stealing a large haul before fleeing.