Brisbane doctor who survived Holocaust speaks out on rise in anti-Semitism

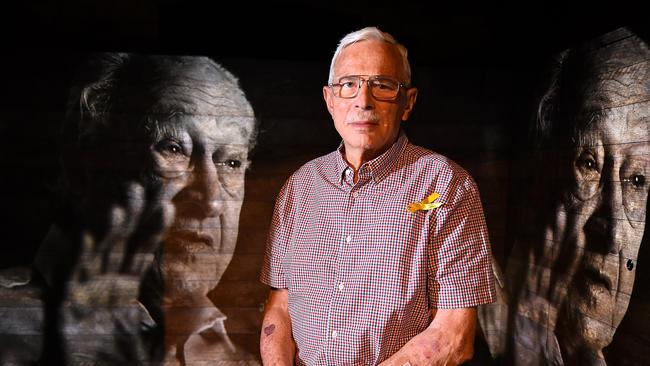

A Brisbane holocaust survivor has a grim message 80 years after the Auschwitz horrors saying “What happened in 1930s Germany which allowed a charismatic leader such as Hitler to gain power... is happening again”.

QLD News

Don't miss out on the headlines from QLD News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

It was a mix up on a railway platform in war torn Europe which saved him from Auschwitz - a strange twist in a train schedule which still occupies his mind 81 years on.

As the world marks the 80th anniversary of the liberation of the Auschwitz Concentration Camp this Monday, Peter Kraus will still be pondering those few seconds on a platform in German occupied Subotica, a border-town in Yugoslavia, in June 1944.

He can’t remember those moments himself. He was aged two.

But what he does know is that his mother, Clara, stepped out of a queue of people (including relatives, “Uncle and Aunt Eisler’’) waiting to be loaded onto a train bound for Auschwitz.

Clara left the queue to go to the aid of an elderly blind man whom she was vaguely acquainted with and who was in a great deal of distress.

In the confusion, Peter and his mum ended up in another queue while Uncle and Aunt Eisler stayed in the original queue.

Uncle and Aunt Eisler perished in Auschwitz.

“I am still receiving information about what really happened,’’ says Peter, 82, who carved out a stellar career in Australia as an obstetrician-gynaecologist before retiring on Bribie Island north of Brisbane.

There is some suggestion a railway bridge was bombed by the Allies which prevented all the train’s carriages getting to Auschwitz.

It’s possible that carriages were decoupled from the locomotive to make getting over mountain passes easier.

Uncle and Aunt Eisler may have been in the forward carriages, which got through before the bombing, while Peter and Clara were in the rear carriages which did not, and were redirected.

Whatever occurred, the heavily pregnant Clara and little Peter were on the crowded train for about nine days, Clara using a little fold-up child’s chair to sit on - a chair now on display at the Queensland Holocaust Museum in Brisbane.

They arrived at a slave labour camp between the village of Viehofen and the town of St Polten in Austria just as the war in Europe was turning in favour of the allies.

In April of 1945 Clara borrowed a pair of pliers from the bootmaker in the camp and cut through the wire fence.

She escaped with Peter, her newborn son Paul, her uncle Jeno Parros, his wife Elizabeth and the couple’s 21-year-old daughter Susan.

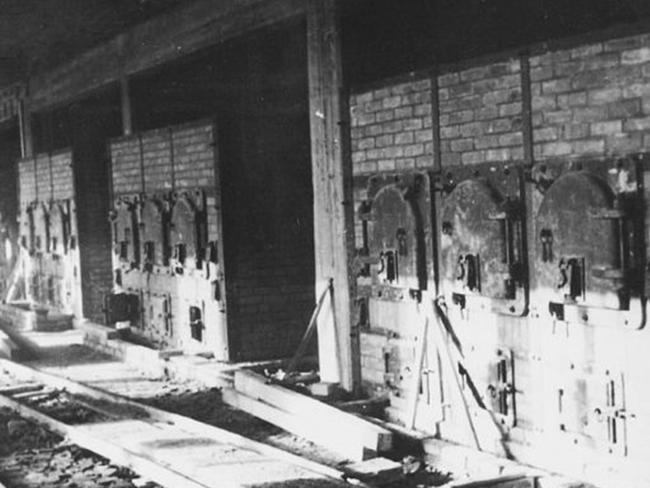

The half dozen escapees later learned that German SS soldiers had come through a few hours after their escape and marched everyone in the labour camp to Mauthausen concentration camp where at least 90,000 people perished during the war.

Those too old or sick to make the trip were shot dead by the SS.

The family then made their way to Australia where Peter Kraus married wife Heather, started a family and thrived.

He not only established a successful medical career but has held academic positions at both the University of Queensland and James Cook University in Townsville while also publishing articles in peer-reviewed journals and giving presentations at international scientific meetings.

Yet it worries him that the history of the Holocaust is being lost.

He believes today’s generation is significant in that it’s the last to have any direct contact with people who were actually there.

As he writes in his book, Slow Train to Auschwitz, first published in 2020:

“They say history repeats itself and it is only by knowing what has happened in the recent past that we can try and prevent that.’’

A racist, bullying element will arise in every society, including our own, he says.

“What happened in Germany in the 1930s was that political circumstances allowed a charismatic leader such as Hitler to gain power and those elements of society were given the opportunity to throw their weight around and everyone, having become accustomed by gradually increasing exposure to acceptance of their behaviour, followed the crowd.’’

Could it all happen again?

It is happening again, he says.

“Under the guise of increased tolerance, our society is losing freedom of thought, freedom of speech, freedom of conscience and freedom of religion.

“It is not alarmist or exaggerated to acknowledge it.’’

Queensland Jewish Board of Deputies president Jason Steinberg, also chair of the Holocaust Museum Board, says Peter’s story is, quite literally, one among millions.

An estimated six million people died in German concentration camps during World War 11, each one representing a tragic story of loss still echoing down the generations today.

The museum, which is playing a role in educating Queensland school kids about the Holocaust, is telling hundreds of those stories through exhibits and testimonials from survivors.

Yet the horrors of the Hamas-led invasion of Israel on October 7 2023, the worst attack on the Jewish community since the Holocaust, has only made the museum even more relevant, reinforcing the ongoing need to let the world know of the barbarism lying just below the surface of any ostensibly civilised society.

“Unless we hear from the people who were there, who have first-hand experience and testimonies which people need to hear and understand, all of this will be forgotten, the evil perpetrated against the Jews will be forgotten,’’ Mr Steinberg says.

“This is more relevant now than it has ever been because of the recent rise of anti-Semitism.’’

“What Peter and his family had to go through is exactly where we are heading unless we all recognise the rise of antisemitism, and take a stand against it.’’

Originally published as Brisbane doctor who survived Holocaust speaks out on rise in anti-Semitism