Why we must debate or die

OUR growing inability to speak and reason with those we disagree with is threatening centuries of human progress, writes Stefan Molyneux.

Opinion

Don't miss out on the headlines from Opinion. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Humanity, it seems, is divided into two categories: those who embrace criticism, and those who attack it.

All progress comes from the former — who often have the dubious distinction of being hated by the latter. Accepting criticism is a foundational act of humility; it is how we all learn. Children are corrected when they misspell a word, miscalculate a sum, or swing their tennis racquets badly. As a result, they improve.

Childhood is spent being corrected. That essential process, however, grinds to a halt for many adults, who imagine they are in possession of perfect knowledge and immune from criticism. Of course, they are not in possession of perfect knowledge — but even if they were, why should they fear criticism? The best tennis player in the world should not fear the serve of a first-time player.

All our moral progressions — the roots and seeds of the modern world — arose from questioning the unquestionable. Slavery was approved practice across the world for all of human history until the late 18th century, when the Abolitionists began to question the morality of owning people.

Mankind’s position in the universe — on a planet orbiting a sun orbiting a galaxy that orbits nothing — was considered heretical for decades.

“Trial by fire” refers to a medieval practice of forcing a person accused of a crime to walk three paces holding a red-hot iron. If God healed his burns, he was innocent.

The modern judicial process of requiring evidence, letting the accused confront the accuser, a trial by a jury of your peers, access to a lawyer — all required the substitution of empirical mortal mechanics for murky divine feedback.

Since the tragically shortened days of Socrates, philosophers have hurled reason and evidence against the accepted beliefs of the time. Our most treasured beliefs must be subjected to rational arguments and empirical evidence — because so many treasured beliefs failed these tests in the past.

The wrenching expansion of morality beyond its original limits produces real progress. The end of slavery was the expansion of the ban on human ownership from whites to blacks. Men can enter into contracts: giving that capacity to women was a rational and moral extension of a universal right. Subjecting political elites to the rule of law, still a shaky proposition, was the extension of universal morality up through the ranks of power. Science rests on the proposition that the age of miracles is over.

Mankind strives to improve, then gets lazy and brittle. As a species, we have not reached the end of our moral progress — there are significant indicators we have gone in some very bad directions. Every moral advancement undermines the status quo, which produces a new status quo that opposes the next advancement.

I am concerned about free speech in the West — there is little point talking about it anywhere else.

Everywhere I go, even if people have a legal right to speak, they censor themselves for fear of being attacked, of losing careers, savings, relationships, families. They fear visits from the police. The interconnected web of conversation called the internet has been hijacked by malevolent forces threatening to disrupt and destroy our capacity to reason with one another.

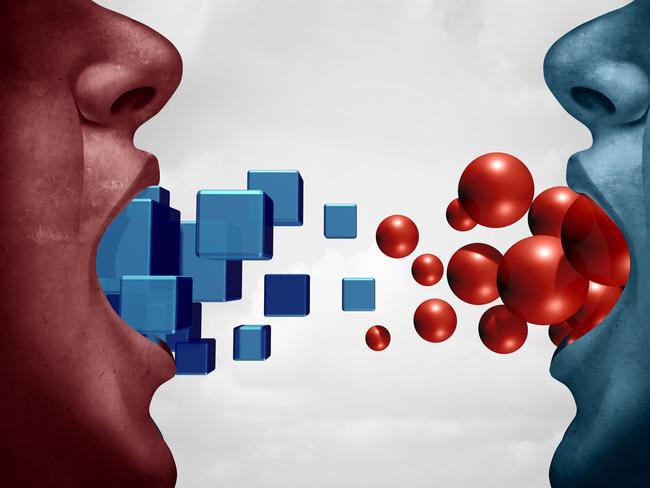

The span and potential of human communication currently hangs like the sun low on the horizon — it is impossible to know whether it is a sunrise or a sunset. We can finally speak with each other, all of us, around the world. Does that mean the world gets better or worse? If we reason with each other, the world improves. If we smash conversations through threats, intimidation, violence and legalese, the world decays and darkens.

The last time humanity had a similar breakthrough in communications was the printing press, which resulted in the immense progress of the scientific revolution, the Renaissance and the Enlightenment, but also, in places, totalitarianism and religious warfare. The capacity to share ideas can produce either the American Revolution, or the French. The Bill of Rights, or the ever-thirsty guillotine.

We will always have disagreements. How do we resolve them? We have only two choices — force, or debate. Civilisation is the substitution of conversation for naked violence. The moment we submit to reason and evidence is the moment we become — or stay — civilised. Many ideas offend many people. If we allow offence to silence debate, we elevate ignorant passions above reasoned discourse, and will lose the freedoms we have inherited — all the freedoms our ancestors fought, bled and died to hand to us.

The philosopher may not always be right, but the enraged mob is always wrong. Surrender to them, and we lose everything.

I look forward to engaging in this conversation in Australia over the coming weeks. We have not finished our moral journey. Let us join hands, in reason, peace and conversation, and strive to magnify the freedoms we inherited — not abandon them to appease an enraged mob that will only trample them, snarl, then come for us.

Stefan Molyneux is the host of the popular philosophy show Freedomain Radio and will be speaking in Sydney on July 28. See www.axiomatic.events