NSW bushfires: Cartoonist Warren Brown recounts the battle to stop Green Wattle Creek fire

The terrifying power of a fire front is something that has to be experienced to be believed, writes Daily Telegraph cartoonist and volunteer firefighter Warren Brown, who has been battling the lethal Green Wattle Creek fire.

Opinion

Don't miss out on the headlines from Opinion. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The lethal Green Wattle Creek fire — the blaze that claimed the lives of RFS firefighters Geoffrey Keaton and Andrew O’Dwyer — has now expanded to alarming proportions, burning its way into the tortuous, tangled wilderness west of Mittagong to the Wombeyan Caves.

Normally during the holiday season, the five limestone caves at Wombeyan are a popular tourist attraction for campers and families, yet simply getting there is something of an undertaking.

Heading west from Mittagong, the caves are only accessible by negotiating a 68km-long single-lane dirt road that plummets rapidly to the Wollondilly River through a seemingly never-ending series of hairpin bends before soaring through even more alarming zigzags, the road carved precariously along near-vertical mountainsides — on one side of the track a wall of rock on the other a breathtaking drop to the valley floor.

Once the road reaches the caves’ facilities and camping area it continues to climb west, zigzagging through dense forest to link up with the Taralga/Oberon road.

To put it simply, there’s one road in and one road out — an unimaginable nightmare in a bushfire.

And now locals’ great fear has materialised. For just over a week the Green Wattle Creek fire has poured its burning fingers into the labyrinthine gullies and ravines encompassing Wombeyan Caves, turning this near-impenetrable region into a cauldron of raging fire.

Like so many other RFS brigades in the region and those from far afield, my local brigade from Middle Arm Wayo in the Southern Tablelands has been tasked with sending trucks and crews to be part of a strike team — a co-ordinated 24-hour operational force to stop the Green Wattle Creek fire from spreading further.

KEEP YOUR HELMET ON

On Friday it was my turn to be part of the strike team.

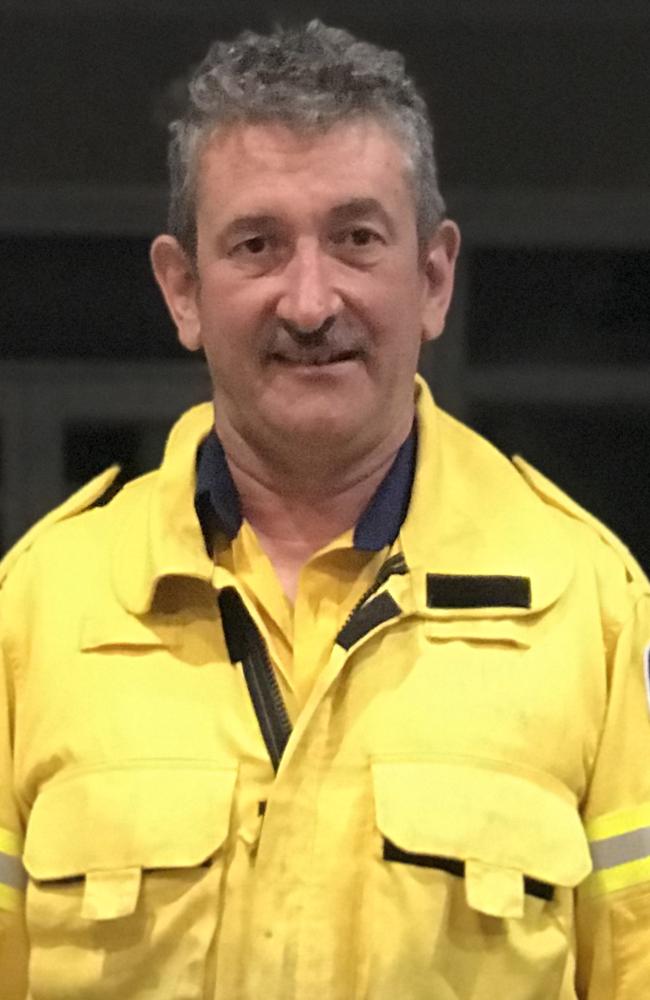

At 6.40am Deputy Captain Daniel Decourt, neighbour and fellow firefighter Ivan Petrie and I climb aboard what’s known as a Category 7 fire truck — a mid-sized three-seater — and headed off for the Taralga RFS fire station where crews from all over the district are fed, marshalled, fuelled, briefed and dispatched north for the Wombeyan fireground.

On leaving, the captain of the Taralga brigade gives me good advice: “Always wear your helmet. A branch came down and hit a firefighter on the head — thank God he had his helmet on.”

From here on in we can only prepare for the unexpected — it’s helmets on, jackets, gloves, boots. The truck is “under lights”, with the eerie flashing of red and blue cutting through the smoke.

“No through road” reads the barrier at the turn-off to the caves and the truck negotiates its way past to begin the lengthy descent to the valley floor.

Overnight, RFS crews had successfully back-burned bush on the northern side of the road, effectively starving the advancing fire front of fuel to stop it in its tracks.

We know if the fire jumps the road into the wilderness to the south, there’d be no stopping it, so we regularly pull up to ensure any small flames and smouldering logs are extinguished.

We’re descending into a world that is now the sole domain of passing convoys of RFS trucks, command vehicles, National Parks 4WDs zipping about and the sound of constantly operating graders and bulldozers clearing blocked roads and creating fire breaks to short-circuit the encroaching fire.

The fire truck is fitted with at least three bands of radios. Communication is imperative so that at all times Fire Control knows where crews are deployed, they know their physical safety, they can receive advice and issue instructions.

Radio traffic is always brief, blunt and unequivocal yet it’s through hearing other conversations that you gain a bigger picture of what’s taking place.

We hear a crew asking for advice. They’d been approached by an agitated resident who owned a shed somewhere deep within the area who wanted to make his way through the fireground to retrieve some of his gear.

The return advice is unequivocal: “Under no circumstances can this individual enter the area.”

The crew — clearly being harangued — replies: “He says he’s got a chainsaw and can cut his way along the track if trees have come down.”

The response is even clearer: “Tell him under no circumstances can he enter!”

We listen, incredulous someone was seriously intending to dash into the fire to retrieve whatever he wanted from his shed. It’s like deciding to run back into a raging war zone because you’d forgotten your glasses.

Across the gully, vast columns of smoke tower above groups of RFS trucks, which seemed so tiny from our vantage point. Radio traffic coming thick and fast from operations taking place on different fronts, as trucks pass us, heading back down to the campsite to refill from a water tanker.

WALKING INTO APOCALYPSE

We are stopped by today’s Strike Team leader who tells us to drive along a fire trail that peels off from a junction on a ridge line — somewhere along there, the fire front is expected to break out.

We head along the track driving across vast sections of fire-blasted rubble that are an iridescent pink — the result of an aerial bombardment of red fire retardant. This place has quite clearly been through an inferno of apocalyptic proportions.

We stumble across what was a cattle yard and to our amazement a house still in tact that somehow survived what was clearly a catastrophic situation.

The owner comes out to greet us — he’s quite clearly been through hell, his house narrowly avoiding oblivion thanks to the brilliant work of the water bombers.

An RFS deputy captain himself, he’s particularly glad to see us and points us in the direction of where the fire front is expected to break out, at the back of what is a sanctuary for brumbies. We’re joined by two other Southern Tablelands brigade crews — from the district of Roslyn and the town of Bigga. None of us have ever met before but there’s an amazing, unspoken camaraderie and ease. I’m particularly relieved as I have nowhere near the experience of these hardened blokes from the bush.

The brumbies in the paddock are clearly nervous — the feeling of the oncoming fire is palpable to everyone and everything — and we can see the pall of grey smoke coming closer and closer.

The fire will run west through the bush along the fence line in front of a fire trail. All the three fire trucks can do is prevent the fire from spreading north toward the horses and houses that have survived the first onslaught.

Daniel, our deputy captain, observes a series of spotfires emerging from the northeast. A bushfire is an insidious, ruthless and inventive enemy, deploying the most seemingly innocuous techniques to gain a stranglehold. Tiny embers landing on bleached, straw-like grass the height of a crew-cut suddenly send the ground black, an ever-expanding cancer of fire that is almost impossible to see but if it reaches the right fuel it will start an uncontrollable blaze within seconds.

Daniel drives the truck around the fire’s perimeter and from the back Ivan and I are extinguishing the rapidly advancing grass fire before it reaches the dead-dry timber to the south.

RISKY BUSINESS

The three fire trucks are lined up in preparation for the oncoming fire to pass before us when suddenly a LandCruiser towing an overladen trailer comes bouncing flat out along the fire trail. The driver pulls up, clearly pleased with himself. He’d somehow made his way into the forest and was able to retrieve his gear from his shed before the fire arrived. He told us he’d had to chainsaw his way along the track to get there, but he’d done it. He then got out to try and reposition everything that he’d thrown in the trailer.

We stare in disbelief.

For a trailer-load of stuff you could buy from Bunnings, this bloke had been prepared to play Russian roulette with an unpredictable catastrophic fire — further, what if one of us had come to grief trying to save him?

He thought he was a hero. I thought he was a thoughtless, selfish dimwit.

And sure enough the fire came, its advance foot soldiers the ever-growing heat and small flames that scorched tree bark and leaves on the ground.

Then a greater force takes hold of the scrub along the fence line and before long the main attack arrives — an inferno soaring to the full height of the trees, creating black twisters of fire and smoke spiralling into the air, burning precisely where the LandCruiser and trailer sat only half an hour before.

The fire burns like a chimney up through the inside of a giant, ancient eucalypt, the top of which belched smoke like a steam locomotive before it collapsed under its own weight with a beyond-deafening crash, sending a mushroom cloud of smoke and dust into the air.

Tops of towering gumtrees were ablaze and we stand waiting for the trees to begin ‘crowning’, where the whole canopy of tree tops relays fire in a sea of flame and heat. It came close, awfully close.

The three crews were operating non-stop in extinguishing whatever the fire wanted to throw our way. And then it seemed almost as quickly as the fire arrived it had rolled on through, hungry to devour more dry bushland.

In time we checked the freshly-burned fireground, the air unbelievably, burning hot, the remains of incinerated trees collapsing before our eyes. That night we headed home. The road back out from Wombeyan awash with fresh, red retardant as the whole place had been under bombardment from small helicopters — a Chinook and the DC10 bomber.

Trees along the road we’d driven through in the morning were now alight and we could see bush well ablaze on the cliffs above us.

We knew those working on Saturday’s Strike Team would have a far worse day than we had.

Filthy, exhausted and rattled, the three of us — and the truck — looked like we’d been put through the wringer. Our last task late that night was to refuel at a service station in Goulburn.

To our surprise a girl came up to us and nervously said: “Excuse me, can I pay for your petrol? I just want to say thank you.”

We smiled and thanked her. It made our day, though of course with our fuel paid for by the state, we politely declined.