Vikki Campion: Money spent on Yes campaign could have been put to good use

The cash splash on an ad blitz telling people to vote Yes to the Voice to ‘impact the 500 First Nations communities without safe drinking water’ could have genuinely helped those running dry, writes Vikki Campion.

Opinion

Don't miss out on the headlines from Opinion. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Hell is a home without water.

In small drought towns, it’s often the teachers who see children in dirtier and dirtier clothes who take action first.

On top of everything they do daily, they wash and hang tiny uniforms to dry on lines where paintings should be pegged.

Mothers with drought babies count rungs on the tank. When there’s no drop from the tap, there’s no way to bathe them or wash their clothes, sterilise bottles or dummies.

When the closest public tap is in a town a marathon away, fresh water is gold.

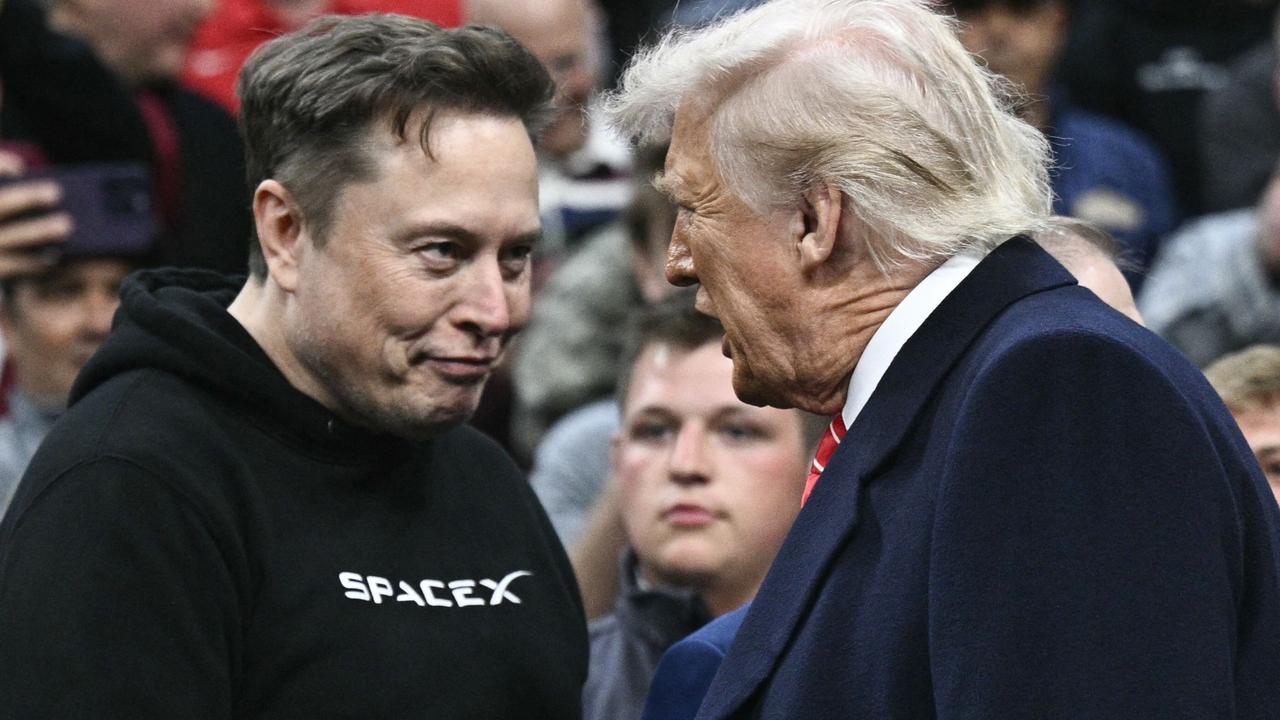

So it is peculiar that sponsored Facebook ads from the Uluru Statement from the Heart identified 500 communities without water, and instead of buying fresh water and tanks, the Yes corporate camp gave millions of donation dollars to billionaire Tesla-driving US tech lords — and still couldn’t move a vote.

It cost $1000 for the Uluru Statement from the Heart page to sponsor this post for a few days: “If you’re not First Nations, the Voice is unlikely to impact your day-to-day. But it will impact the 500 First Nations communities without safe drinking water.”

If the Uluru Statement from the Heart campaign knows 500 communities are without water, why don’t they ask Wesfarmers for tanks? Shareholders would be much happier funding actual water infrastructure than enriching PR shills.

Instead, Wesfarmers CEO Michael Chaney, whose company Bunnings sells cheap water tanks and could donate them to households in these 500 communities, gave $2m to Yes23, who fed it down the overstuffed gullet of Silicon Valley.

The betrayal to Indigenous people will not be that the Yes vote loses but that the funds raised to help communities out of poverty were foolishly fribbled away on videos created by global ad agencies based in New York and pumped into feeds on Facebook, Instagram, YouTube and Google Ads, based in California.

That the grand beneficiaries of the Voice referendum have been to those a universe away from trying to feed or clean a child without water.

The equivalent of a single donation from NAB ($1.5m), Westpac ($1.75m), Commbank ($2m) or ANZ (about $2m) has been funnelled into Google — with Yes23 squandering around $1.8m just on Google advertising, spending $114,000 on their ads on Tuesday this week.

In the final days in the lead-up to the vote, interim data shows at least $1m worth of advertising on Facebook, including from unions, Labor members of parliament and other Yes support camps.

They wasted thousands on ads calling on some good old-fashioned keyboard activism by “adding a Yes frame to your profile picture”.

Another ad, variations of which cost donors at least $125,000 to push out for a week, says: “For 250 years, we haven’t listened to the people that have been here for 65,000.”

This rubbish invalidates every Indigenous democratically elected local government councillor, every elected Indigenous member and senator, every elder who has been working to close the gap for the past 18 years.

And where significant inroads have been made in improving school attendance, year 12 graduation, tertiary qualifications, school nutrition and life expectancy.

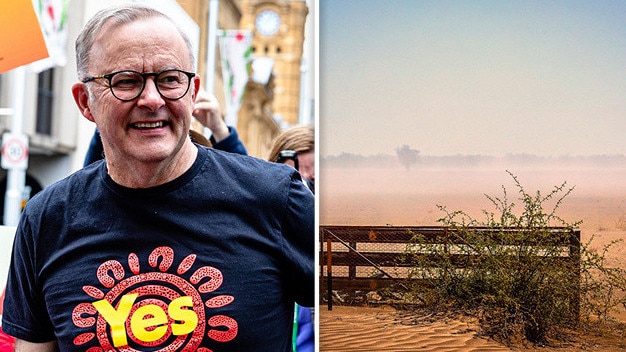

For all Prime Minister Anthony Albanese liked to wax on about transparency before the election, we will not know who and how much was donated to this ad spree until next Easter, when the publication date for the Transparency Register is set for April 1, 2024.

Will the big end of town still be as passionate come Easter Monday? Will the millions of dollars that slid so easily from corporate Australia, for airbrushing and special lighting go to the problems they finally recognised — many of which were not an issue of race but of poverty, an affliction that doesn’t count in colour?

Between advertising and the referendum itself, nearly half a billion dollars has been spent – enough to build a number of smaller dams, or more than 200,000 water tanks to hold 22,500 litres each.

Not only would that fix the water problem in remote communities but it would also significantly boost Australian manufacturers, who make the tanks right in regional NSW and who employ Indigenous people.

Unlike the banks.

According to the Census, the Indigenous proportion of the workforce in NSW financial and insurance services industry is less than 1 per cent, compared to the state average of about 2.5 per cent across all industries.

After their champion score of virtue payments was revealed this week to be of the tune of about $7m — in addition to lending staff to the campaign and hosting Yes advertising on their websites — will the big four consider giving Indigenous people jobs, or keep the branches open where they live in regional communities now?

If they genuinely believe their own hype, they have shown they have acknowledged the issue and have the cash to fix it.

Energy Minister Chris Bowen told parliament last sitting: “More than 90 per cent of Indigenous Australians who live in remote Australia suffer energy disconnections at some point in the year.

“Well over two-thirds suffer those disconnections more than 10 times a year.”

Does the Energy Minister seriously need another layer of bureaucracy to tell him what to do here?

This campaign shows what moves votes is not money and advertising but experience.

If those communities don’t get fresh water and storage infrastructure, what shallow shills the big end of town has become.

Got a news tip? Email weekendtele@news.com.au