Annette Sharp: The day I pissed off Harry M Miller

THE first time I met Harry M. Miller, in about 1990, he extended a hand, asked me if I’d like to get to know him better, and then handed me a copy of his autobiography, complete with autograph, unasked for. It was the start of a long and often rocky professional relationship.

Opinion

Don't miss out on the headlines from Opinion. Followed categories will be added to My News.

THE first time I met Harry M. Miller, in about 1990, he extended a hand, asked me if I’d like to get to know him better, and then handed me a copy of his autobiography, My Story, complete with autograph, unasked for.

The second time I met Harry M. Miller, about six months later, he handed me a copy of the same autobiography and told me to call him.

He wanted to have dinner.

If there was one thing Harry M. Miller believed in, it was the making and maintenance of his

own legend.

If there were two things Harry M. Miller believed in, it was his own well-honed legend and his innate ability to sell anything.

If there were three things Harry M. Miller believed in, it was that legend, his ability to sell anything, including lost causes, and his ability to flirt with, conquer and bed any woman he set his sights on.

Back in 1982, some eight years before we met, Harry had been sentenced to three years in jail for his part in a ticketing scam involving the collapsed company Computicket. He served 10 months at Long Bay and Cessnock Correctional Centre, the incident virtually destroying the reputation he had built during the 1960s and ’70s as a showman and entrepreneur following the success of the stage musical Jesus Christ Superstar and later The Rocky Horror Show, which he produced for Australian audiences.

With the collapse of Computicket, the Australian media turned on Miller, writing him off as a criminal and fraudster. It hurt.

By the time Harry and I met, he was still angry, bitter and determined to remake himself. As a result he was reaching out to younger and younger journalists who he hoped would abide by his rules and write only flattering things about he and his clients, chief among them radio broadcaster Alan Jones, whose rise in the industry helped restore Harry financially and socially — before radio’s cash for comment controversy set them back a decade on.

On and off for two decades, Harry and I duelled. We had some blistering fights.

He would contact me with the offer of a story, either in the interests of his clients or possibly to undermine a rival, and then he would withdraw the offer, saying he could get a better run elsewhere.

It was always the same. Harry gave nothing away easily. He was hard to like, yet impossible to dislike for long.

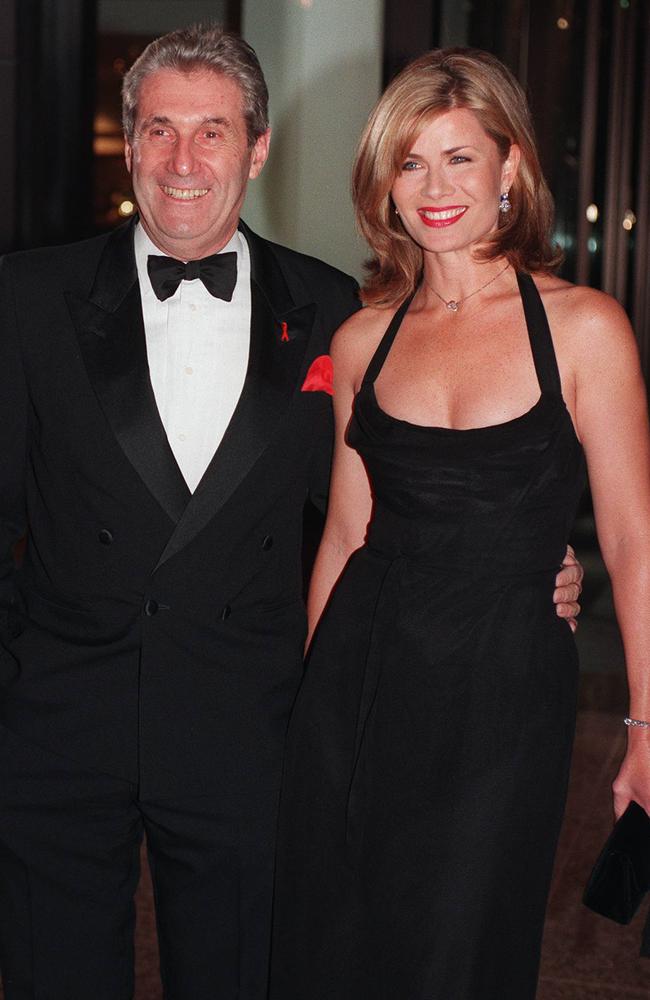

Harry M. Miller with Deborah Hutton in 1997.

Dealing with Harry could be infuriating, yet it was necessary if you were trying to write about Sydney stars for he had represented some of the biggest — among them Graham Kennedy, Jones, Maggie T, Ita B and one-time Grace Bros model Deb Hutton, the Jennifer Hawkins of her day, with whom Harry had a 10-year relationship.

When we were getting along, Harry could be a useful source, though you could never sidle up to him at a party and put something quietly to him for Harry was very deaf.

A quiet inquiry “Harry, is it true (his client) Lindy and Michael Chamberlain have split up?” provoked a shouted “What?”. This in turn spurred you to ask the secret question louder and louder until, on finally hearing it, there was only one way the conversation was going to be resolved — with a loud blast heard by every journalist in the room.

Due to his self-admitted wandering eye, Harry’s sexual conquests frequently brought us to grief.

He never really forgave me for publishing the news that Hutton, post breakup with Harry in 2000, had moved on with women’s hockey player Danni Roche.

Over the dozen or so preceding years, Hutton had been moulded by Harry into Australia’s favourite girl next door model. She had contracts with Holden, Qantas, The Australian Women’s Weekly — bread and butter mum and dad brands. My story, to Harry’s mind, put those contracts (and his 25 per cent cut) at risk.

Following my revelation he issued a statement: “Deborah Hutton has not in the past, nor will she in the future, be held to ransom to comment on her private life.”

Married and divorced three times, his final enduring de facto relationship would be with pie maker Simmone Logue.

By then in his 70s, the relationship didn’t stop Harry’s wandering eye and soon I was again on the phone to him to put rumours of new dalliances to him.

In Harry’s inimitable style, he decided to own the rumours and in 2009 penned an article for a Sydney broadsheet detailing his philandering.

“My wandering eye is something I have struggled to control all my adult life and even now I’m 75 it causes plenty of heartache for those who are close to me, none more so than Simmone,” he wrote.

Luckily for Harry, who died last Wednesday after a struggle with dementia, those loyal to him, including Logue, remained intrigued to the end.