Erin Molan: We need tough talking on China in the Pacific

The Greens will try to convince you that current global hostilities do not threaten Australia. They think the only evil in the world is a coal mine or a car. It’s not even an ignorant attitude, it’s borderline criminal, writes Erin Molan.

Opinion

Don't miss out on the headlines from Opinion. Followed categories will be added to My News.

If you think that consensus and diplomacy are the answer to all the world’s problems, ask the Ukrainians how they are going.

Ask President Volodymyr Zelensky whether the years of ‘talks’ with Russia worked or whether giving up Crimea and the provinces of Luhansk and Donetsk since 2014 was a move which ensured peace and stability.

Ask the Philippines if they are happy with China’s rejection of international law which has now resulted in the militarisation of the South China Sea.

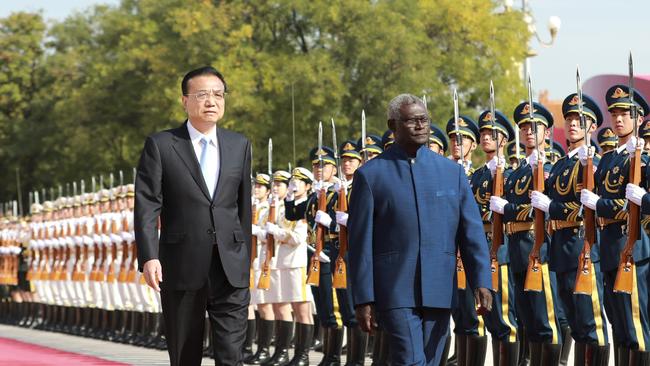

In future we might even be able to ask the Solomon Islands if their security agreement with China put them in a better place than the Philippines, or Ukraine, or in fact any of the world’s democracies.

This week’s announcement of a signed security deal between the Solomon Islands and China is rightly sparking debate and raising legitimate questions over whether this is a failing of our own government.

Did they do enough to look after our neighbours in the Pacific? Is it climate change driven? Was it because Zed Seselja was dispatched to negotiate at the 11th hour instead of Foreign Minister Marise Payne? I wouldn’t have thought so.

We can always do things better but sometimes it makes no difference. If you want to look at this issue bluntly you only need to look as far as the old adage ‘money talks’.

The Chinese Communist Party doesn’t operate the way we do. Nor do the Solomon Islands. Diplomacy is critically important and, while it operates within a framework of broad-based accommodation of cultural differences, it doesn’t always achieve results.

China is on the move in our region and it appears that not even Henry Kissinger could have stopped the agreement being signed.

The Belt and Road initiative is a powerful insight into how China believes diplomacy works. Put simply, they buy their way.

They attempt to gain political leverage by spending up big. Building infrastructure, sporting facilities and cultural precincts is all part of a power play and anyone who believes otherwise is naive.

Having good relationships between all countries in the world is a noble aspiration and better than the alternative but sometimes what we stand for and believe in matters more.

The Greens will try to convince you that current global hostilities do not threaten Australia. They think the only evil in the world is a coal mine or a car. It’s not even an ignorant attitude, it’s borderline criminal.

This week we heard from their ‘Peace and Disarmament’ spokesperson Jordon Steele-John, who boldly and confidently declared: “I don’t see China as a military threat to Australia.”

If it had been a line out of Yes Minister (Google it kids) I’d have still thought it beyond parody but to come out of the mouth of an Australian politician in 2022 is beyond embarrassing — it’s terrifying.

It’s also going to be an awkward conversation if Labor and the Greens form government next month and look to implement their foreign policy agenda.

Steele-John believes that any Australian opposition to the China-Solomon Islands deal is offensive because the Pacific nation is a “sovereign country that is seeking to build relationships with its regional neighbours as best it can’’ yet Labor leader Anthony Albanese has slammed Prime Minister Scott Morrison for failing to intervene.

He’s called it a “massive foreign policy failure”. So which one is it gentlemen? If the Greens are calling the shots in a minority government then God help us all.

Diplomacy is undoubtedly a critical element of government machinery. I spent much of my childhood in Indonesia as the daughter of an Army, and then Defence, diplomat at the Australian Embassy in Jakarta.

I witnessed firsthand the foundation of this art of managing international relations with what was then the most important neighbour we had. Did it make us, as Australians, invincible? No.

Did it stop what was going to happen in East Timor? No.

Was I still, along with my siblings, evacuated during 1998 when the Soeharto regime fell after 32 years? Yes. Were there still issues between the two countries? Of course.

You can have the best diplomats and foreign policy in the world but diplomacy doesn’t always work. Diplomacy without the backing of military, economic and trade measures can be nothing more than a polite conversation.

A strong military complementing a nation’s diplomatic efforts is the only universal language when it comes to global security and, even then, there’s no guarantee of a successful — or peaceful — outcome.

The stronger our own Defence Force is, the more effective our diplomacy will be. Peace is always the objective but it inevitably involves deterrence and, in today’s world, without a strong, lethal military, deterrence is almost impossible.

This is a balancing act between diplomacy and force.

We must understand the limitation of each and we must be prepared to use both. Most importantly, we must know exactly when to employ each.