Clare Armstrong: Albanese’s olive branch to Dutton on Voice detail should not be ignored

Anthony Albanese’s plan for a joint Labor and Liberal lead committee to oversee the Voice legislation won’t end the referendum “detail debate,” but it should, writes Clare Armstrong.

Opinion

Don't miss out on the headlines from Opinion. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Fear of the unknown, a lack of detail, confusion and misunderstanding have fuelled many Australians’ concerns about the Voice proposal, but with one move Anthony Albanese is hoping that can change.

Love it or loath it, the potent No camp line if you “don’t know, vote no” is the only slogan of the entire referendum campaign to have somewhat stuck in the national consciousness.

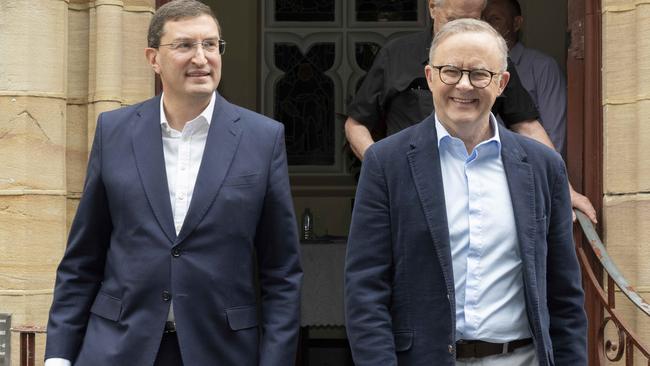

But after months urging Australians to err on the side of caution if they did not have the details they were after, Opposition leader Peter Dutton is now on the receiving end of an invite to fill in the very blanks he has been warning about.

The Prime Minister’s confirmation he will form a joint Labor and Coalition-led committee to oversee the Voice legislation should the Yes campaign pull off what would be a stunning turnaround on October 14, won’t end the detail debate.

It should.

Albanese’s commitment to seeking bipartisanship on the Voice is timely reminder of the primacy the parliament would always hold.

If all parliamentarians get a say in how the Voice looks, then it can hardly be said to be some scary, uncontrollable, third chamber-esque governing body with unbridled power and influence.

But it’s a point difficult to execute with less than three weeks to the referendum.

Earlier this year the PM started using a simple analogy to describe the process by which a Voice would be created.

To vote in the referendum, he explained in January, was like answering the question ‘should there be a bridge built over the Sydney Harbour?’

If enough Australians agreed with the basic idea, then the parliament would take that mandate to design the bridge, decide its location, cost and other logistics.

The government and Voice proponents have been at pains to explain the specific form and function of an institution does not belong in the constitution, and in fact should remain at the whim of the parliament to ensure it is fit for purpose in perpetuity.

Advocates have also been conscious of the fact the 1999 republic referendum was derailed by a split in the Yes case over the preferred model for selecting a head of state to replace the monarchy.

In a few weeks, many proponents of the Voice may look back on the decision to avoid prescriptive detail in hindsight as the potential difference in what is likely to be a very close referendum result.

There is certainly merit in the idea Albanese should have produced draft legislation to answer questions like how many people will be on the committee, how long will they serve and how will they be chosen.

Many Australians are asking these questions out of genuine curiosity and a desire to understand how the Voice would work, and it was a great failing of the government to be outright dismissive of such inquiries early in the debate.

But it’s laughable to think filling in any of those parameters would have satisfied those in the right faction of the Coalition party room determined to oppose the proposal.

If anything, those details would likely have provided fodder for even more questions to undermine the Yes case.

Take for example one of the specifics in the design principles released by the government earlier this year.

In these broad outlines it was confirmed the Voice committee would have equal representation of men and women.

This has led to questions of how it would be possible for a democratically elected body to achieve gender parity.

I’ve previously observed that if Australian high schools have for decades devised student election systems that allow for the selection of a girl and boy co-captain, surely the nation’s political brains could arrive at an appropriate mechanism for the Voice.

But the answer is irrelevant.

The point is that even where the most rudimentary detail has been provided, it’s been used to attack the Yes case.

It’s easy to imagine the veritable field day an entire piece of draft legislation would have offered to staunch opponents of the cause.

The Yes campaign has undoubtedly suffered by not being able to answer the questions Australians have about the Voice, which if answered may have sufficiently allayed the fears of voters who feel the referendum is a step into the unknown.

The Coalition will argue the PM’s olive branch is proof the detail behind the Voice should have been settled before the referendum was called.

The success of a Voice to Parliament always rested on bipartisan support for the advisory body, now Albanese is testing whether he can achieve it after the fact.