Australia’s defensive stability in the region is with nuclear energy

It’s clear that the way forward for Australia’s defensive stability in the region is with nuclear energy, writes Warren Mundine.

Opinion

Don't miss out on the headlines from Opinion. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Australia’s adoption of nuclear-powered submarines as part of the AUKUS agreement is arguably the most significant policy and strategic decision of the Coalition Government.

Australia’s defence capabilities need to cover vast distances. Nuclear-powered submarines have superior stealth, speed, range and endurance because nuclear propulsion provides massive power and nuclear-powered submarines can go their entire life without refuelling.

For an isolated country like Australia, diesel submarines (best purposed for coastal defence) would leave us vulnerable and weak, and the effort needed to attempt to compensate for this was costly and complicated. That’s why Australia’s inability to adopt nuclear-powered submarines underpinned virtually all failures, cost overruns and delays in our submarine procurement for decades.

Nuclear power is the solution to another challenge facing Australia: the increased pressure from foreign governments, international organisations and, increasingly, the corporate and investment sectors to upend our economy by abandoning fossil fuels to achieve net zero emissions over a rapid timeframe.

Successive Coalition Governments resisted this pressure. But with Trump out of the White House, and the UK and US governments forging ahead with net zero by 2050, the pressure for Australia to fall in line is increasingly difficult to ignore.

The challenge for this Coalition Government isn’t just about policy. It’s also about how to implement any policy without breaking the Coalition into pieces.

This is a seismic issue within the Coalition. Malcolm Turnbull lost his leadership over it. Twice.

It’s no secret the Coalition has two influential and opposing camps on climate change policy: one that’s all for rapid transition to net zero; the second, which includes most Federal Nationals as well as many regional and conservative Liberals, that’s not.

In particular, this second camp don’t agree that Australia, a miniscule emitter in raw terms, should adopt policies that threaten industries and jobs when large emitters such as China continue to increase emissions and lap up the industries and jobs we discard.

And the fact is, these arguments, and the practical outcomes of climate change policies when put before the Australian people, have seen resistance to climate change policy rewarded in the ballot box more often than not.

There’s perhaps a third camp: the pragmatists, who realise there’s a limit to Australia’s ability to resist the pressure to conform, regardless of the merits of these arguments and the political realities, and there’ll be increasingly adverse impacts for Australia if we do.

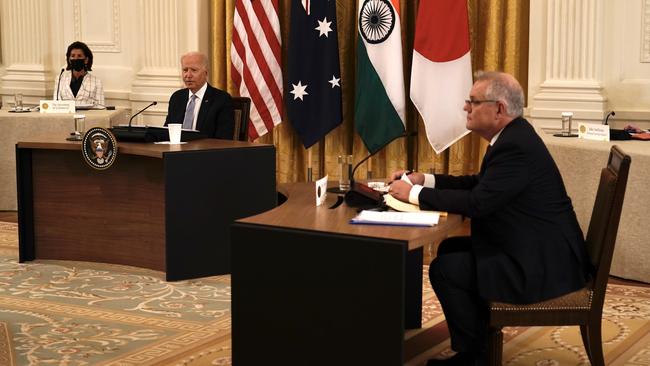

I believe Scott Morrison falls into this third camp. That’s why, while recently in Washington for talks among the Quad group of countries he confirmed the government is developing a plan for net zero emissions and joined a series of announcements from the Quad group indicating this would be “preferably by 2050, and taking into account national circumstances”.

Already there are unhappy rumblings from the Coalition’s second camp.

But, being a pragmatist, I believe Morrison has no intention of following his predecessor’s path and upending his leadership or the Coalition as a result of an internal brawl.

Speaking with SBS’s Anna Henderson last weekend, the Prime Minister gave an indication of how he intends to direct climate change policy and handle the ensuing fight in the next election, saying that “Plenty of people like to make commitments … but not enough people are making plans and we’re making a plan”. Anyone can point to a commitment and make whatever claims they want about what’s required (or not) to get there.

A plan will enable the Coalition to reassure voters about key industries, jobs and the economy as well as put pressure on Labor to come up with specific measures of its own, which can be scrutinised. Nuclear energy should be part of the Coalition’s plan. Nuclear energy is safe, reliable and used all over the world. It produces zero emissions and abundant energy, 24/7, regardless of weather.

Adopting nuclear energy would enable Australia to expand and grow high-energy industries and agriculture, not shut them down; to adopt rapid electrification of land transport without overloading electricity production and transmission; and to build a domestic world-leading nuclear technology capability.

Deleting four words from one piece of legislation is all that’s required for consideration of nuclear energy projects in Australia, with stringent safety and environmental standards unaffected.

Politicians from both sides of politics knew for decades that nuclear power was the only realistic and suitable solution for Australia’s submarine capability given the threats facing our country.

Until now they didn’t have the means or courage to act on it. And the widespread support for AUKUS among Australians demonstrates that adopting nuclear technology is not politically impossible.

Politicians also know that achieving net zero in Australia without nuclear energy is unrealistic.

This Coalition government should show the same courage on energy and allow nuclear power to be part of the mix as part of Australia’s climate change policy.

And, in doing so, it could turn climate change policy into something every member of Coalition can unite behind.

Nyunggai Warren Mundine AO is author of Speaking My Mind and Warren Mundine – In Black and White