Angela Mollard: When taking a picture for posterity is the wrong thing to do

We are always in a rush to capture a moment to add to the thousands of photos we already have on our phones and shared to a wider audience, but there is a time to put the phone away.

Opinion

Don't miss out on the headlines from Opinion. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Waterfalls. Gorgeous things. The love child of nature and magic. Yet as I stood behind the most startlingly beautiful one I’d ever seen I felt frustrated.

I was trying to capture the tumbling water on my camera but the cascade was too close and the spray was threatening to soak my phone and the rocks were slippery and the sun was in the wrong place even though in real life it was making the droplets sparkle like rain on a spider’s web.

And that’s when I realised – on the third of a 13-day drive around Iceland – that I didn’t need a picture. Rather, what I’d saved so hard for and craved during those long days at my desk, was an experience. An inhalation of something other. A sliver of awe – not recorded but remembered so that in years to come it might be thrown up by the tumble dryer of my mind to be freshly enjoyed all over again.

Photographs are great. But in our determination to snap, filter, brighten, frame and crop we’re not just supplanting the long-trusted libraries of our minds but weakening the other senses which are vital in laying down memories. .

A photograph is just an image; it can’t capture the squawk of an arctic tern or the smell of cinnamon on pastries, or the malty, salty, doused deliciousness of a vinegared chip or the clasp of a child’s hand

Our desire to feed social media has changed how we absorb the world. Words and pictures have always been the tools for telling stories about our travels but we’re no longer simply capturing a few blurry slides to bore the grandchildren. Photographs used to be a personal catalogue and memory prompter. Now we create “content” for an audience who are so visually ambushed their retinas must be bruised.

I have thousands of photographs on my phone but do I flick through them wistfully remembering moments from the past? Not at all. My favourite memories are happily cluttered like bric-a-brac on the shelves of my mind.

There’s the night of my daughter’s birth which her dad and I failed to photograph but comes to me in glorious kaleidoscopic life and colour when my monkey mind needs calming. I remember the slick of rain on the midnight streets as my contractions hurried our drive to hospital and the sense of an alien force bearing down on my pelvis.

Then her first cry and the shock of dark hair and, later, the wonderment as her womb-trapped limbs began to unfurl.

It’s the same with the first two days I spent with my partner. We were entertained by whales, fighter jets, an ice-cold ocean and, of course, each other. I think he took one photograph of me beside a pandanus tree but I can’t be sure because I’ve never seen it. The memory matters more.

As I stood behind Seljalandsfoss waterfall last week, lamenting the less-than-ideal photographic conditions, I realised that my focus, literally, was on content not memories. And so I made a quiet vow. Every time something scenically stunning caught my eye I would try to experience it through all my senses, not just the lens.

On a lagoon glimmering with icebergs I listened, hearing the occasional crack as chunks broke off and bobbed in the silent water. On a lava field overgrown with moss, I sat down only to laugh out loud at the superior upholstery. At a bar in Reykjavik I savoured a caramelly pale ale called Bondi, pointing out to the gruff barman that it was the name of a beach in Australia. In Iceland, he told me, the word means farmer. I have no picture of it, only the amber memory. There’s more: the whistle of wind and the discomfort of sweat chilling after a hike to the lip of a vast volcanic crater. The sulfurous scent in a tiny perfectly warm geothermal pool we found on a roadside. Ptarmigans, cackling and waddling among the heather, the white-feathers on their limbs looking for all the world like little leg-warmers. Their tufty, fluffy legs had me humming Olivia Newton-John’s Physical.

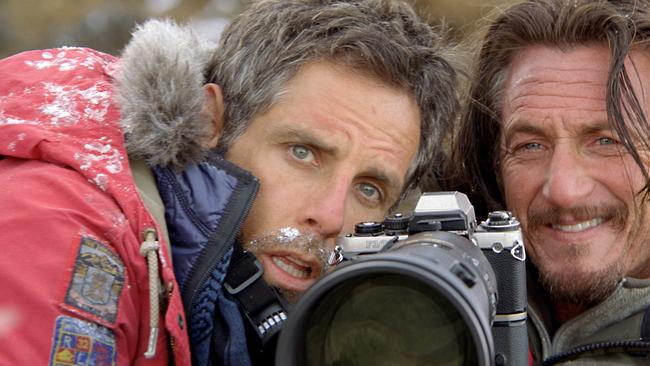

One day the landscape seemed so familiar we wondered what memory it was attached to. “I’m sure this is the road Ben Stiller skateboards along in The Secret Life of Walter Mitty,” pondered my partner. That evening we downloaded the movie and after establishing that he was right we realised we’d forgotten the whole point of the film. If you remember, Walter is trying to track down photographer Sean O’Connell, played by Sean Penn, who he believes has the image to feature on the final cover of Life Magazine. As they sit on a mountain where Sean has waited for weeks to try to capture an image of a snow leopard, the animal suddenly comes into sight in his lens. He hands the camera to Walter who is equally awed.

“When are you going to take the picture,” asks Walter.

“Sometimes I don’t,” says Sean explaining how he just wants the moment for himself. “So I stay in it. Right here.”