Andrew Rule: Tracing the roots of Masa’s evil killer Sean Price

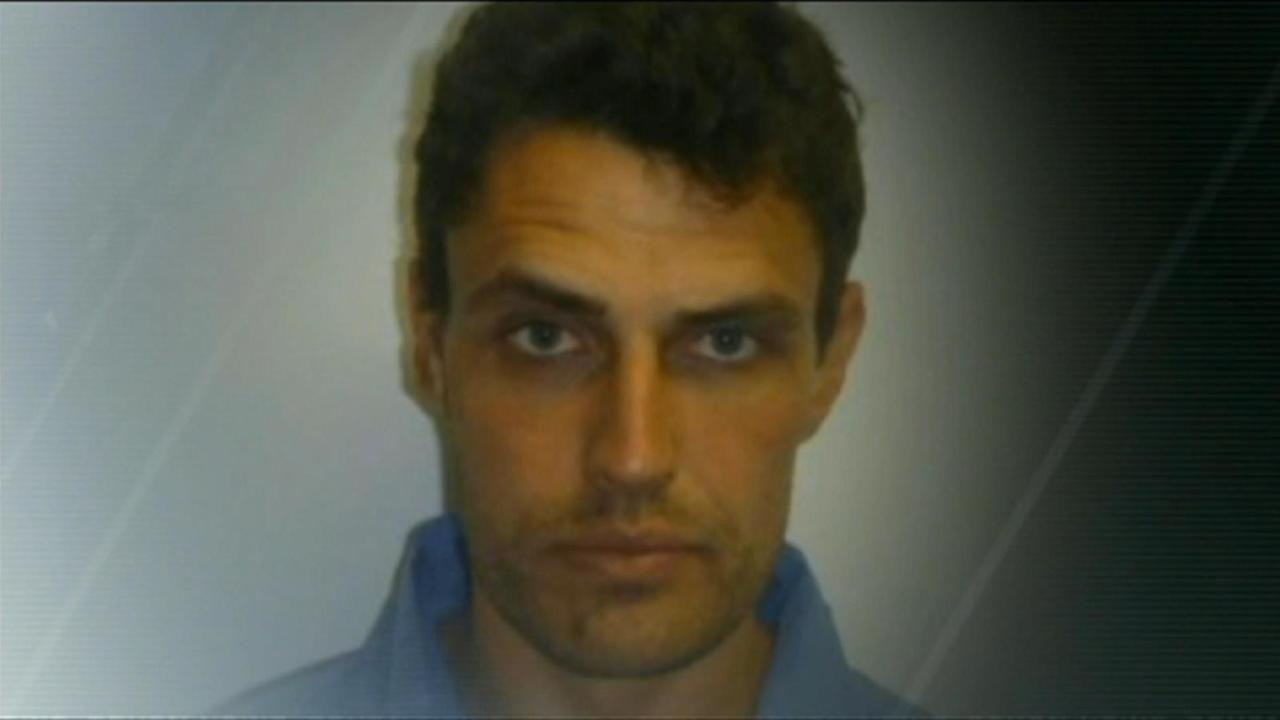

Ten years have passed since Sean Price murdered 17-year-old Masa Vukotic in a crime that chilled Melbourne. Andrew Rule probes his violent past — and the forces that may have shaped him into a brutal killer.

Opinion

Don't miss out on the headlines from Opinion. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The man who killed Masa Vukotic is bad and probably mad but not stupid, and that partly explains why he is still one of the most high-security prisoners in the state.

A decade after he committed a crime that chilled Melbourne, the killer’s warped intelligence is a good reason to keep him separated from most inmates in a secure unit of Victoria’s most secure prison, Barwon.

Underneath the calm exterior and his attachment to prison routine, Sean Christian Price is never completely trusted by those who know him best.

Now 41, Price faces another 30 years before being eligible for parole.

It is 10 years this week since the brooding young man stalked and killed the 17-year-old schoolgirl in a Doncaster park.

He chose Masa at random after criss-crossing the suburbs looking for a victim, but the attack was premeditated.

Police were able to piece together his movements and moods beforehand which showed he had been building up to a motiveless murder.

Signs of Price’s growing menace showed up even in his choice of reading matter. He had borrowed books from Brimbank library that reflected not only ghoulish interests but an increasingly dark and disturbed state of mind in the month before Masa’s murder.

Price was reading about serial killer Ivan Milat — and about a crazed Swede named Thomas Quick, who was convicted of multiple killings but then re-tried and acquitted after revealing he’d made dozens of false admissions.

It was as if Price was preparing for what was ahead when he rose before dawn on Monday morning, March 17, 2015.

Price was living in public housing at Albion, in a flat effectively used as a “halfway house” for ex-prisoners. His history of extreme and erratic violence made him a terrible candidate to be back on the street.

Price wasn’t hard to spot in security footage. He was tall, lean, lantern-jawed, handsome in an edgy way.

Film shows that Price got to Sunshine railway station at 5.42am and caught a train to Flinders St station. Masa Vukotic, meanwhile, was preparing for school as usual at her family home in Doncaster.

Masa was a bright student who worked hard. Her long-range plan was to do Law.

While Masa spent the last day of her short life at school, Price took a convoluted route using multiple trains and buses that eventually led to Doncaster. After the dawn ride to Flinders St, he went to Glenferrie, then back to Albion in the west, then to Sunshine, Footscray, Southern Cross and Jolimont.

Around the time Masa was eating dinner with her family, Price was on a bus that let him off at Doncaster. He walked towards the Koonung linear park.

Masa finished dinner, put earphones on and walked from her street to the track through the park. It was there, hidden by bush, that Price attacked.

As he would tell police 48 hours later, Masa just happened to be “the one.” The murder, following that of ABC staff member Jill Meagher less than three years earlier, caused mass rage and grief.

It was inevitable the repeat offender would be arrested because there were images of him on security footage on buses to and from Doncaster. But he stayed free long enough to rape a woman in a Christian bookshop in Sunshine two days later before being arrested when he reported to a Corrections office.

Price showed no signs of remorse in his court appearances, making obscene gestures, ranting and ignoring the process. But he paid attention when his lawyers proposed to raise defence arguments based on his past, notably his abusive childhood.

Price apparently felt so strongly about this he sacked his defence lawyer, Mandy Fox (later a judge), for attempting to raise matters in his defence. A violent and abusive childhood produced the violent and abusive adult he became.

The Vukotic murder was when Price’s name became notorious but it wasn’t the first time he had shown his propensity for monstrous behaviour. A long history of unpredictable violence has made him one of the state’s highest security prisoners.

Ten years after his arrest, those who have dealt with him say Price’s volatility appears to have eased but they do not trust him. While he is strong enough to offend, he will always be considered dangerous, which is why he has spent his entire sentence so far at Victoria’s most tightly-run maximum security prison.

Barwon insiders say that, like many high-risk prisoners, Price needs structure and routine to keep him calm.

One source who has had dealings with Price said that although he is twisted, he’s not a fool.

Price has a good memory, reads a lot and can coherently challenge decisions he disagrees with, the source said.

“He’s not stupid — he’s an intelligent bloke.”

But Price’s background and unpredictability keep prison staff wary — and him separated from other prisoners most of the time.

“Who’s going to sign off on him playing with someone else?” a former prison officer said. “He could flip in the blink of an eye.”

Plenty of people found that out the hard way even before the Masa Vukotic murder.

In 2003, Price was jailed for a series of sex attacks in the eastern suburbs which he committed by following victims home after asking them for directions.

Three years later, he made headlines while at the Thomas Embling Hospital, a secure facility for offenders with mental problems, by punching then Health Minister Tony Abbott as he toured the facility.

While on parole over the eastern suburbs sex crimes in 2011, he attacked a female psychiatrist.

That resulted in cancellation of his parole and the imposition of a 10-year supervision order compelling him to live at Corella Place, a special facility for released sex offenders near Ararat known as the “Village of the Damned.”

He was ordered not to take drugs or alcohol, to attend treatment programs and live under a curfew, but those restrictions did not curb his tendencies.

At Corella, he assaulted other inmates, threatened staff and smashed their property in a series of outbursts.

Price was sent to maximum security at Port Phillip Prison where he was later charged with threatening staff. And yet he was put back on the street, a catastrophic decision slammed by a Supreme Court judge.

Hindsight is no comfort to victims or their families, but it seems clear that Price was a terrible candidate for the unsupervised apartments in Albion used to house former prisoners.

When Price pleaded guilty to murdering Masa Vukotic, it posed the question often asked about people like him.

Was he born bad or was he made that way? Nature or nurture?

In one court appearance, his counsel raised two aspects of the history of the disturbed and dangerous man scowling and gesturing in the dock.

The first was that he claimed descent from the “Mutiny on the Bounty” ringleader Fletcher Christian. The second was that he had been physically abused as a child.

No one pointed to a link between those two supposed facts but it’s tempting to conclude there is one.

It is almost 236 years since Price’s ancestor, the Bounty master’s mate, Fletcher Christian, led the infamous mutiny against Lieutenant William Bligh near Tonga, an escapade that has echoed down the decades through books and films that put romantic myths above ugly facts.

First the mutineers forced Bligh and loyal crew members into a glorified rowing boat, knowing they risked drowning or dying of thirst before they could reach safety.

Christian’s worst desperados abducted six Tahitian men and 18 women and took them a long way to hide on a tiny island so remote it took months to find. This was Pitcairn Island.

The mutineers burned the Bounty rather than leaving it to attract the British warships that would be sent to hunt them.

Subtract two centuries of Hollywood-meets-desert island myths and there’s the recipe for Sean Price’s “Pitkerner” forebears: mutiny, abduction, sexual slavery and arson. Murder came later.

Eight mutineers and their captives had arrived on Pitcairn in 1790. By the time an American whaling ship visited the island in 1808, all but one of the eight mutineers, including Fletcher Christian, had been killed in fights with each other and the Tahitians.

By then the enslaved women had given birth to the first generation of islanders. They included Christian’s son, Thursday October Christian, whose descendants are among a few hundred “Pitkerners” surviving on Pitcairn and Norfolk Island and scattered around New Zealand and Australia.

The creepy combination of criminal and cannibal trapped on an island bred a closed society where child sex abuse was rife and accepted under the catch-all excuse that “it’s the Polynesian way”.

Supporters of that “way” included eccentric millionaire author Colleen McCullough, who married a “Pitkerner” on Norfolk Island and was quoted as saying, “it’s Polynesian to break your girls in at 12”.

The truth was exposed in 2000 when British police arrived to investigate the rape of a teenage girl. They spoke to dozens of women, some on the island and some who had fled from it, and uncovered a network of interwoven sex abuse going back eight generations.

Each victim was related to the men being charged with similar offences against other young girls. Husbands, brothers, fathers, uncles and cousins were part of systematic abuse that had been a way of life on Pitcairn — and most likely also on Norfolk Island, where many “Pitkerners” had moved in the 1850s to escape overcrowding.

Some defended the “tradition” of under-age sex. Others were ashamed. Almost every man on Pitcairn was investigated and six were eventually convicted of 35 charges in 2004 after trials that attracted international attention.

An English journalist, Kathy Marks, lived on the island to cover the trials and later wrote a book titled Lost Paradise.

Marks believed the convictions were the tip of an iceberg of depraved practices that affected the “Pitkerner” clans even when they moved to mainland communities.

None of which excuses Sean Price’s evil acts. But it might explain the forces that shaped him, whether before his birth or after it.

What it doesn’t explain is why the Parole Board would release someone so dangerous against the orders of a judge. It seemed a random choice, like tossing a coin.

When Sean Price won the toss and was let out, Masa Vukotic lost her life.

Unlike Thomas Quick, the Swedish “murderer” who made a string of false confessions in the 1990s, Price is guilty beyond any doubt. But something Quick’s veteran lawyer told a reporter rings true about what created him.

“I don’t like people much in general,” he said. “But if you spend so much time with a client, you see the person behind the headlines. It all starts with a little boy under a Christmas tree, playing with toys and it ends up very tragic. Somewhere along the line, everyone is a victim.”

Originally published as Andrew Rule: Tracing the roots of Masa’s evil killer Sean Price