IN the kitchen, waiter Jarrod Morton-Hoffman put a knife down his pants as he handed colleague Joel Herat a Stanley knife and scissors to hide in his apron.

Feeling more alone and isolated with each hour that passed, the hostages were becoming convinced they would have no choice but to save their own lives.

Morton-Hoffman also pocketed the basement key card from the office.

COPS’ FURY AT LINDT SIEGE INQUEST ‘WITCH HUNT’

He hoped he could find a way to slip it out under the door to police. And he drew pictures and messages on the back of business cards and slipped them under the back door of the cafe.

No one ever got them. In the police operations centre, the tactical adviser was trying to get ahead of the game.

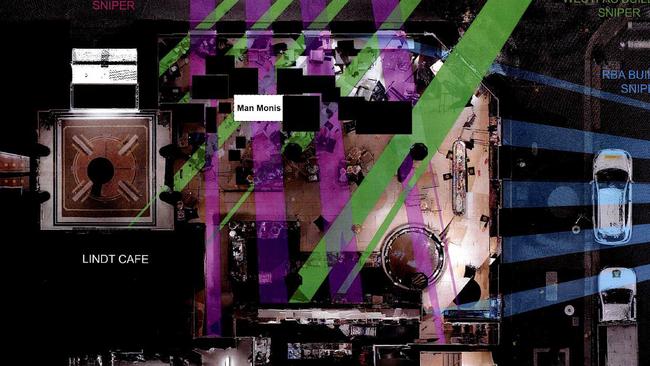

Offices from the Tactical Operations Unit had been all over the building — but concluded there was no point of entry without alerting Monis.

Negotiations had reached stalemate. There had been no move by the negotiators on any of Monis’s major demands — no phone call from Tony Abbott, no offer to talk on ABC radio and no IS flag.

Monis never picked up a phone or made a call himself. The negotiators had still not spoken to him directly.

As one of the hostages tasked with speaking to negotiators and calling media on Monis’s behalf, Marcia Mikhael’s anger boiled over when she was told by a negotiator that Abbott was a “very busy man”.

“Why doesn’t anyone care?” she said during one call. “They are ... simple demands. He is not asking for a criminal to be released from jail.”

In her terror, she was getting increasingly angry.

“They have left us here to die,” she told 2GB in another call.

CCTV FOOTAGE OF THE SIEGE ENDING

Along with Mikhael, some of the remaining 13 hostages had spent the afternoon making videos in front of the Shahada flag and posting them on YouTube on Monis’s orders.

Among them were Selina Win Pe, Julie Taylor and Louisa Hope. In one, Mikhael was filmed saying the police were doing nothing.

They emailed videos and messages to TV stations, but none were played. Monis started to capitalise on their grief and frustration.

“See the government doesn’t care,” he told his captives. He said if anyone died, it would be Tori Johnson’s fault because he was “the manager”. Obsessed with his own publicity, Monis became increasingly aggravated that his messages were not getting reported.

At 12.28pm, police had moved back some officers from near the cafe after a demand by Monis — but did not ask for anything in return.

At 12.56pm, they moved cars back after another demand by Monis. Again, they asked for nothing in return.

Distraught families of the hostages had started arriving at a meeting point nearby.

Some had received texts from loved ones inside the cafe who, like Johnson, had hidden mobile phones.

The negotiators thought the hostages were being looked after. “Doesn’t need to release anyone as he is looking after them, having toilet breaks etc” they noted in their log.

It certainly didn’t feel like that inside the cafe.

Hope, a sufferer of multiple sclerosis, needed her medication. On her trips to the toilet she prayed in the stall.

Her mother Robyn told people she would spit in Monis’s face if they ever got released. Despite appearing outwardly calm, Morton-Hoffman threw up twice.

Monis goaded Johnson. Everyone laughed to humour him.

Monis was even using the hostages as human shields. At one stage he had Puspendu Ghosh and Viswakanth Ankireddy sit in front of him with his gun pointed at their backs.

Mikhael collapsed to the floor vomiting and Dawson got down to help her.

When Monis started talking about releasing a hostage so they could talk directly to Amnesty International for him, Katrina suggested Julie go. In the end, no one left.

When Johnson needed the bathroom, Ma and Morton-Hoffman were ordered to take him there. “If he doesn’t come back, I’m going to shoot one of you. Make sure he doesn’t run away,” Monis said.

Then-police commissioner Andrew Scipione and his deputy Cath Burn were briefing the state’s Crisis Policy Committee and fronting more media conferences.

As senior executives, under the protocol they had no operational role.

The hostages had taped Monis’s Shahada flag to a window. At the forward command post, someone had delivered a real IS flag but a clear decision had been made not to give it to Monis.

At 7.05pm, while at St Vincent’s Hospital for a check-up, Paolo Vassallo received a text message from Johnson: “Tell the police the lobby door is unlocked. He’s sitting in the corner by the waiting station on his own.”

Vassallo immediately passed it on to a detective taking his statement.

THE ANALYSIS

Yet it was not until 7.50pm that the tactical adviser in the police operations centre saw it when it turned up on iSurv.

Johnson’s message was redundant in two ways by then.

The police could not act on it because their commanders had controversially never approved a Deliberate Action plan which would have allowed them to take control of the situation and storm the cafe under their own steam.

The bosses were not taking the chance that Monis really didn’t have a bomb. The other reason was that a sniper had Monis in his sights.

The three sniper teams had kept their Remington 700 bolt-action rifles trained on the cafe, moving only to go to the toilet.

At 7.35pm, Sierra 3-1 in the Westpac Bank had his armour-piercing ammunition with copper zinc jacket and a tungsten core aimed at Monis’s head — the first time the terrorist had exposed himself to attack as he sat close to a cafe window on the Martin Place side.

Sierra 3-1, the sniper co-ordinator, knew that to make the shot work, he had to hit his target in the brain stem so he would literally fall in a heap with no opportunity to detonate a bomb.

The sergeant radioed in that he had “observation of POI (person of interest) … and he could take a shot if required.”

But the police could not be certain that Monis had not put his distinctive bandana on a hostage to trick them.

If a hostage had been shot or injured, the snipers could shoot at will because the action would have triggered the Emergency Action plan.

As it was, Sierra 3-1 had no legal basis to take the shot.

Had he done so, he could have been charged with murder. At 4.15pm, the building manager had told them that the glass in the Martin Place windows was not bullet resistant.

Sierra 3-1 thought he had a good chance of getting the shot in but only learned afterwards that while his ammunition would have pierced the cafe windows, it would never have gone through the plate glass in the Westpac windows.

To break the glass first would have alerted Monis.

After 10 minutes, Monis moved out of sight.

Sunset on December 15 was about 8pm. At that time, Monis ordered the lights be turned out to stop police looking in.

He was already jumping at shadows, and in the dark the blue flashing Christmas tree light in Martin Place was annoying him.

At 8.38pm, Mikhael was given the job of calling negotiators to get them turned off.

At 9pm, Scipione visited the police forward command centre with then-police minister Stuart Ayres for what he called a welfare check.

From about 10pm new commanders took over with Assistant Commissioner Mark Jenkins replacing Murdoch and a detective chief superintendent taking over at the forward command.

Scipione told Burn to go home and he would see her “bright and early” the next morning.

At 10.51pm, Burn made a controversial call to Jenkins which he said involved negotiations. Burn has denied such discussions — they would have been against protocols.

Six minutes later, at 10.57pm, her boss made an equally controversial call to Jenkins, which he described as a welfare call.

The scribe working with Jenkins noted in the log: “DA (Direct Action) plan to occur as a last resort COP (commissioner of police).”

Scipione denied discussing a DA plan with Jenkins. Again, to have done so would have been against protocols.

At 11.59pm, Scipione sent an email to Jenkins, acting deputy commissioner Jeff Loy and a media adviser telling them to take down the YouTube video of Mikhael criticising police.

Scipione has denied it was a direction, which would have been against protocols.

As Burn was signing off at about 10pm, Johnson texted his family: “Love you all. Still alive. Very scared.”

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

Police probe Scots incident

An incident involving students from The Scots College is under investigation by NSW police after a teen boy was allegedly physically and verbally abused, and had beer thrown all over him.

Residents recall inferno chaos, jerry cans found near scene

The number of homes lost in a Central Coast fire has grown as residents recall the terror of the fast-spreading blaze, as dozens of fires continue to burn across the state.